Problematize Your World

Cool is not The Future

A recent pair of articles on The Verge and FastCompany have me thinking about problems. They’re ostensibly about Google’s next step in the long process of marketing Glass to a wider consumer audience, bringing it from the fringes of the Explorer Program, to the “Geek Sheek,” status that Google has been aiming for, and often missing, since they released a promo video as far back as early 2012 (oddly the promo’s opening shot features a MacBook…). While there’s been much back and forth about privacy concerns and “Glassholism,” with restaurants around Google HQ banning the devices, and explorers reporting unexpectedly fierce reactions to the devices, the controversy is probably mostly good for Google. But these recent pieces had me really wondering about something we’ve talked a lot about here at Startupyard recently.

What Problem Does Google Glass Solve?

That may seem like a stupid question, but I think the answer is revealing of why, after decades of this same concept floating around in the tech world, one of the biggest tech companies in the world, with its endless resources and bottomless R&D budget, is having anything resembling problems marketing a device that can only be described as incredibly cool. Apple sold the iPhone literally before they were finished making it work. Their first presentation of the product was with a prototype that was not actually fully functional.

And it is cool right? A computer that you can wear on your eye? Imagine all the cool stuff you can do. A million ideas spring to mind instantly. Don’t they? There’s just one problem with that, that I see. Google Glass doesn’t solve any problems. What does it do that tells you: this thing is going to add something to your life, the way you do things, that will make your life better, easier, more fun, or more productive.

Ok, why is that important? Well, simply put, Google is positioning Glass as the “next step,” in a tech evolution that has taken us from typewriters to smartphones in 70 some-odd years. But what is often forgotten is that, every single step of the way, each major leap in that evolution has been based primarily on solving a problem (or a range of problems), without creating more problems than doing so was worth. This kind of approach is in the DNA of Google as a company, from the search algorithm, to Gmail, to their mapping efforts- all of their most successful ventures have been in problem solving. And it’s often in areas where they aren’t actively solving problems that they run into real trouble: Google+ springs to mind.

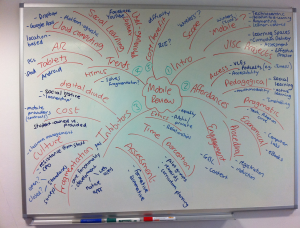

Innovation is Problem Solving

Let’s take that step by step. The modern tech industry has its predecessors in 3 slightly different fields. One is the computer, the second is the television, and the last is the typewriter. Essentially, the consumer computer industry was born in the 1970s when it was slowly realized that the processing power of a computer could be combined with the familiar input mechanism of typing, to allow for programming interfaces that were based on symbolic logic systems that people would be comfortable with almost right away. The television or CRT monitor was the ideal medium for displaying that information (replacing heat-activated printer rolls and punch-cards). The modern computer was slowly assembled out of components that people were familiar with: a typewriter, a TV, and a processor. As obviously as these concepts are to us today, they were not so 50 years ago.

Virtually every major advance in consumer computer technology has been based on the act of solving problems that existed with this initial paradigm. Magnetic tapes and punchcards were slow, so floppy disks and hard drives were developed. Keyboard based manipulation was sluggish, so joysticks and later mouses were introduced. DOS was intimidating to consumers, and the learning curve made a whole class of software products unattractive to potential customers, and so window-based operating systems were developed. MP3 players replaced CDs because of their carrying capacities. Later, the concepts already familiar to consumers from the computer and software industries were combined with the mobile phone to solve another major problem: people wanted to access the internet from anywhere; smartphones were born out of a problem that needed to be solved. They were cool, but cool just gets you in the door. It doesn’t make you essential.

When Steve Jobs introduced the Macintosh in 1984, it was the cool factor that got him the most press, but it took years for the concept to catch on. It was so cool and new, that people had a hard time understanding what problems the concept actually solved. It was too advanced for its own time, lacking the power and memory, as well as the screen real-estate, to do all the cool things one could imagine doing with it. As iconic as it is, the Macintosh in its original form was a massive flop, and it lead to Jobs’ unceremonious firing not long after. And in some senses, the Macintosh concept was never fully vindicated. Even today, there are no products in the market quite like it, unless you consider the modern notebook computer to be its spiritual successor, in which case, it was only about 15 years ahead of its time.

Can An Idea Be Too Far Ahead of its Time?

The problems that the Macintosh solved were ultimately, and for many years, not solved in ways that made the sacrifices made in its design worth making. And many of those sacrifices are familiar when we talk about Glass. The screen was too small, making it unattractive to business and gaming clients (spreadsheets and typing then being a huge reason to own a computer, along with gaming), and the processor was underpowered for the applications it was running, making it slow. It was small but heavy, and depended on a large power source and clunky peripherals, meaning that even though it seemed like something you could take with you (I remember our first Macintosh had a carrying sleeve), it was hell to actually transport.

Glass occupies a similar dark spot. It is clunky and obtrusive, and It only seems to be mobile, but its battery and processing power don’t support the potential it offers. The focus on cosmetic changes from Google belie these issue, and what it actually offers are things that people are much more comfortable doing in other ways. You can’t read on it or watch a film, you can’t talk to someone with it and have them see you, you can’t use it to send emails (it’s difficult to input complex text), and you can’t comfortably view a map on it unless it’s of a very small area. The potentially revolutionary advantages for a product like Glass are still years from bearing any fruit: a voice activated AI that can use what you’re viewing to help you in your daily life is still years away from being practical, and the advantages of actually having it perched on your forehead seem dubious even if it did work. All the things you can do with it are cool, but none of them solve a problem. And as more than one user has found out, the presence of Glass makes people uncomfortable in a way that smartphones and even bluetooth headsets never did. Having Glass on your face creates more problems than it can solve.

Cool is not Innovation

Why does this matter to us at Startupyard? Or to any startup? Simply, it illustrates a common problem. Google got very far down the road in creating a product that has yet to justify its own existence. A big company can afford to take a chance like that, but can you? Cool is not innovation, or at least, it is not innovation that works in the tech business. A lot of successful products are very cool; in fact, being cool is an important part of being successful, but being cool cannot make your product a success. What will make your product successful is the urgency it creates in the consumer to buy. If you don’t have that, you don’t have a product as much as a curiosity. And that urgency has to be based on the merits of the product you’ve created, and not on how it looks, or how cool it is- but what problems it actually solves. That’s it, it’s that simple.

Could you leverage the technology in Google Glass to create a killer app that *does* solve a problem that makes Glass worth wearing? Because recent 3rd party promo videos are mostly full of activities that most people either shouldn’t do (read emails while you ride a bike?) or wouldn’t want to (view advertisements in a store? Take notes in a meeting?). Granted, Google has just now opened development to 3rd parties, so thousands of people are about to have the opportunity to prove me wrong. That’s the approach you should have to your products: what would make a device like that worth having?

This isn’t actually a screed against Google either. They are bringing their game to a new level, and offering developers like you a new set of problems to sink your teeth into. They are betting big that they are building a world that you will want to work in. And while we’re not focusing on Glass development at SY, the same rules apply to any idea for a startup. The same basic questions have to be asked.

Convince Me I have One Problem, and Fix that Problem for Me

As our applications filter in during this final week, we’re looking for a number of things. Of course we want to see innovative, cool product ideas, but we are mostly looking for founder teams that are focused on solving problems. What does your product do, that makes the life of a customer easier, more profitable, more productive, safer, or more fun?

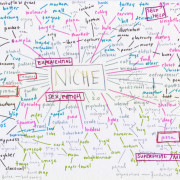

Problematize Your World

If I’m the customer you’re aiming to win, I will buy if you can convince me of one thing: your product will do one of those above things. Because no matter how cool it is, I don’t buy anything I don’t think I need. So look around you right now. What is inefficient about your life and daily activities? What sucks the most to do? What is hardest to get done, or to get other people to do? Could you leverage data in a simple, clean and straightforward way to solve it? That is the kernel of a great idea: turning an annoyance, an inefficiency, or a lack of something into a problem that needs solving.

And when it comes to a business plan, yours has to depend on the bulk of your customers being like me, and not like the rich idiots (or super geeks) that buy things just because they’re cool.

[ssba]