SY Alum Decissio Uses AI to Accurately Predict StartupYard Investments

You may remember Decissio, a Batch 7 StartupYard alum that has been working on the “Jarvis for Investment Decision Making.” Earlier this year, the company announced its kick-off product, an intelligent dashboard for VC investors and Accelerators to evaluate and monitor companies they invest in.

Decissio aims to go beyond a typical investment dashboard by combining up-to-date company data with complex big-data based probability models and machine learning algorithms, helping investors to continuously evaluate their investment decisions.

As Decissio and founder Dite Gashi continues to gather data and build the company’s flagship SaaS product, they have focused on piloting their approach with small controlled experiments.

One such pilot has been in partnership with StartupYard. Decissio’s Mission: to process all of StartupYard’s applications for Batch 8, our latest batch starting next week, and deliver predictions on their success based on a variety of factors, including written applications, founder profiles, founder/market fit, and the current state of the company.

Dite Gashi: Founder and CEO at Decissio

The numbers are in on this pilot, and they’re very promising. We’re not ready to stop reading applications or doing our own research just yet, but we’re now confident that Decissio can be a big part of making our application process better, fairer, and more efficient.

The following case-study is a co-production of Decissio and StartupYard, written by Dite Gashi, and Lloyd Waldo. A more detailed write up and analysis will appear shortly after publication at Decissio.com. For more info on the technology and related work, please visit Decissio.com.

Warning: This post is long and contains big words. Skip to the bottom for a bulleted Tl;Dr

Good Small Decisions = Big Positive Outcomes

The StartupYard application process doesn’t happen all at once. It involves a long series of smaller decisions. Does a startup have a unique idea? Does it fit into our mentor group and experience? Do the founders have enough experience? Is there strong competition in the market?

Some decisions are even more granular: did the founder answer questions thoroughly and clearly? Were they responsive in detail?

Small details often reveal big trends. But a human mind isn’t set up to think in that direction. We aren’t programmed to carefully add up small decisions to make big ones. Enter Decissio, whose mission was to apply a machine-learning approach to small decisions we make in the application process, not to override the judgement and experience of our evaluators, but rather to augment it with important insights.

StartupYard Alum Decissio.com uses #AI to accurately predict future StartupYard startup investments... Click To TweetThe Framework

An application to an accelerator consists of a relatively small data set. We have a written application, founder profiles (on LinkedIn), sometimes a website, and whatever has been written about the company online.

Rarely do we have hard financial data on the companies, in some cases because there is no company in existence, and so the founding team has no financial data to look at. Nor do we have much access to the IP teams are working on. We have to rely on what founders say, and what they have done in the past.

But a bunch of small data sets together make up a bigger data set. Decissio examined over 1300 previous applications to StartupYard, along with the rankings our evaluation committee has generated, and used that data as a benchmark for incoming applications.

They found a number of statistically significant trends in that data. Startups that were successful as applicants to StartupYard could be ranked point-by-point, according to the following framework:

- A Completeness Score: how thoroughly the application is filled in, and with how much quality information.

- Effort Score: The quality of the writing in the application, particularly the responsiveness of answers, and the scope and variety of detail provided.

- Relatedness Score: how closely a founder’s profile and experience matches the content of the application

- Founder Linkedin Score: The completeness and quality of a founder’s LinkedIn profile

- Media Mentions: The number, quality, and sources of mentions of the company or product online, along with sentiment analysis

- Money/Work/Revenue Generated: The ratio of previous investments and time spent on the project to real revenues (if any).

- Spell Check

Believe it or not, Spell Check is powerfully predictive of application quality. Note to founders: always use Spell Check.

The Analysis

This is where the historical data from previous StartupYard applications comes in. While it’s not very useful to directly compare older applications to newer ones, because the topics and ideas in them are often so different, it is useful to weight the importance of the different factors in the framework according to their impact on previous decisions.

Furthermore, the final analysis includes proprietary algorithms by Decissio that can dynamically weight the outcomes for individual teams, based on cross-referencing between different data sets. For example: Decissio’s AI can adjust its expectations for the Effort Score, if the founders are experienced in marketing and sales, or have no such experience. Thus each team is examined according to its own merits, and not an evaluator’s less informed expectations.

As “calibration,” or maintaining consistency and fairness of scoring across a large number of applications is a significant problem with humans, Decissio can re-calibrate an evaluator’s judgement to keep them from penalizing teams for the wrong reasons. As the standardized testing field has long known, human scoring can be so inconsistent that a significant amount of scoring time (even up to half) must be devoted to calibration in some cases.

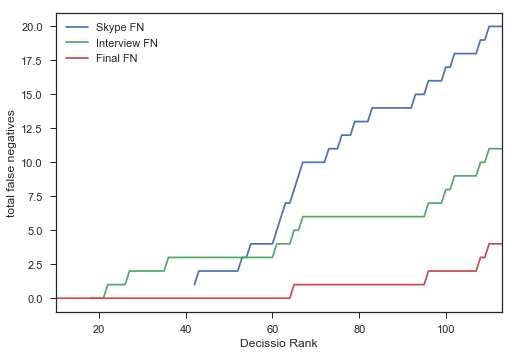

Since our evaluations involve multiple rounds with a Pass/Fail outcome, each examining more and more detailed information, highly predictive models can be built for an application that will make it through round 1. A less predictive but still strong model can be built for round 2, and a much less accurate, but still useful model can be built for round 3, and so on.

The chart below shows overall predictiveness of the approach over multiple rounds. StartupYard uses a “first past the post” system of ranking, where the ranking cutoff for each round is smaller. This means that in round one, 70-80% of applicants are rejected. In round two, just over 50% of the remaining applicants are rejected, and in round 3 (which are day-long in person interviews), only 20-30% are rejected.

None of Decissio’s bottom-ranked 63 startups were ultimately selected, meaning that virtually all of the first round of evaluations could be handed over to the AI, leaving a much smaller pool of applicants to evaluate, and allowing the human evaluators to use a much lower cutoff, in a smaller, better initial pool. In this scenario, only 20% of human evaluated startups would need to be rejected in the first round.

We would expect false negatives to rise, as Decissio gets only one pass at the data, and with each round, human evaluators gather more data, which causes their behavior to diverge from the model.

For example, if use of Spell Check is 90% predictive of the Pass/Fail rate for round 1, it may be only slightly predictive of the success rate of round 2, and by round 3, it may lose its predictive power altogether. By the time an application involves a detailed look at a founder’s CV, and personal interviews with that person, other factors can arise that vastly outweigh any minor inattention to detail, like spelling.

Or the predictiveness curve can go in the other direction as well, with certain data only gaining predictive power in later rounds. Media mentions may have a low predictive power in the earlier rounds, and become more powerful later on. This can be because a company with a low early round score for Relatedness or very high Money/Work/Revenue ratios, can have many mentions in the media, but also fatal problems in their business, team, or technology. Thus, hype is not strongly predictive in Round 1, but by Round 3, it becomes a major asset to an applicant. Once all other factors are examined, media exposure becomes an affirmation of market fit, demand, or interest.

How Well Does This Work?

Decissio’s Success rate in the first round of applications (the on-paper evaluations), was 73%, far exceeding random chance. The accuracy dropped as expected in subsequent rounds where evaluations focused on personal interviews, from 50% in the 2nd round, to 20% in the final round. Still, this means that exactly half the time, a startup that passed the first interview with our selection committee was predicted to do so by Decissio, based only on their written application and profile.

There are two ways in which this kind of analysis can be useful. Either it can be used to identify applications that have a high likelihood of success, or it can be used to filter out those with the lowest likelihood of success.

Decissio Picked the Top 2 Ranking Finalists

We don’t have enough data to be able to confidently say that an application will definitely fail. However, on the opposite side of the scale, the results from Decissio’s analysis did correctly identify StartupYard’s two highest human-ranked finalists, and placed both in its own independent top ten prediction.

Decissio Picked the 100 lowest-rated applications with 89% Accuracy.

Still, the most immediate benefit of Decissio’s approach is in the earliest rounds, where pass/fail decisions are by design based on less human-focused information than the pass/fail decisions in later rounds.

This theory holds up with Decissio’s results: their bottom 100 applicants in this pool of applications (out of around 130), was 89% accurate, meaning that only 11% of the time, we determined a startup to be worth advancing, while Decissio did not. Clearly, in terms of identifying a lack of potential, Decissio’s approach is already very effective.

Further mining of the available data could produce a much more precise prediction. For example, by analysing co-founder and founder/investor fit according to the work histories and digital footprints of both can theoretically yield very reliable predictions of compatibility, which in turn raises the chances of success or failure for a startup.

These factors would require a different kind of data to solve; a kind of data we don’t collect systematically right now. But this kind of approach, which treats people as nodes in a system that has its own features beyond those of individuals, has been deeply developed already, particularly on the level of enterprise management consulting involving things like the Meyers-Briggs Type Indicator Test.

It may prove true in the future that a set of personality tests of some kind are more predictive of success in a particular accelerator program or industry, than the content of an application, though we don’t know what that test would look like, or how it would be used.

SY Alum Decissio.com predicts first round StartupYard application decisions with 89% accuracy, picks two finalists. Click To Tweet

Potential Applications:

Time Saving

Decissio was able to predict with strong accuracy (73%), the likelihood that a startup would make it through the first round. This means that evaluator’s mental resources can be focused more on rounds in which more human-level data is being examined, particularly personal interviews and meetings.

An evaluator can spend relatively less time making early-round decisions, because Decissio can compare cursory evaluator consensus to its own scores, and “call out” the circumstances in which these do not match for further study. There is less of a chance that a good application will be “overlooked” in this way– a constant fear among startup investors dealing with many applications.

Bias Reduction

While a human with experience can “skim” an application and be able to tell it isn’t strong, that subjective evaluation is highly prone to error and internal biases. Very poor spelling could cause a human evaluator to give up on an application, whereas an algorithm might see past this issue and find more value in the startup than a person would look for.

This process could also serve as a check against more latent biases, such as gender, age, nationality, and sexual orientation. While it’s difficult for a human to differentiate between their instinctive reactions to people based on conditioning, and their objective evaluations of people in a professional context, an algorithm can demonstrate more consistency in that regard. Biases can’t be eliminated even this way, but they can be better controlled.

Thus, Decissio can be a check against the human decision making process, enhancing it without replacing it.

Fighting the “Best Horse” Problem

Decissio’s approach can also serve to fight the “best horse” problem, whereby a candidate with a strong outward appearance can advance well into the selection process without revealing sometimes severe deficiencies.

The best horse problem is one of reinforced selection bias. Imagine you have 10 horses, and you send them all running around a track. Then judging by the outcome of the test, you give special care and attention to the fastest horse, believing that it above the others has greater potential as a champion.

In this way we sometimes pick winners for all the wrong reasons. The horse to finish first can finish first for a number of reasons not having to do with potential as a racehorse. Cheating for example, or luck. Likewise, the last horse around the track can be the one with the most future potential.

In our application process, a very strong written application or interview performance can mask a basic weakness in the founding team’s experience or ability. It’s only much later that these weaknesses reveal themselves in a lack of tangible results from the company.

Startups can and do advance very far in accelerator programs while still lacking the core abilities and disposition needed to thrive. It can take a long time to recognize a fraud or a fish out of water.

Creating More Useful Feedback

Another thing this big data approach can solve is the information problem. What happens frequently with accelerator applications, as we suspect happens in many fields, is that successful written applications contain a near-perfect mix of description and data. Something like the “golden ratio” often described in mathematical analyses of artworks and natural proportionality.

The human mind likes a certain level of balance in the information it receives. When a person writes, they tend to favor either information or analysis, but only experienced writers know how to mix the two into pleasing and easy to read narratives. It’s a problem even good writers frequently struggle with.

Too much writing about ideas, and the application seems too “light.” Too much data, and it seems too dense or too technical. In formal writing analysis, this formula is often used to describe balance between facts and ideas, where the value a is descriptive and creative writing, while b is supporting data and factual information. Those familiar with the classic “5 paragraph essay” often taught in schools, will recall the same proportionality. About 3 parts of persuasive writing, for every 1 part of factual basis.

This type of training is not universal even among professionals, which sets up an arbitrary test of writing skill that may not be as relevant to the outcome as we tend to believe. If our job is to train people how to be better entrepreneurs, then we fail at that mission from the beginning if we can’t differentiate between someone who deserves our help, and someone who doesn’t.

By offering feedback on the strength of an application according to the above mentioned metrics (Completeness, Effort, Spelling, etc), Decissio could potentially improve the chances of failing applications where the main problem is poor writing.

An opportunity to improve an application is also an opportunity for us to see value where it is hard to spot. Telling an applicant that their application is failing because of style and substance can help those applicants to better express themselves, and thus deliver us more opportunities to find quality teams.

Conclusions

StartupYard and Decissio pilot project shows that AI assisted investing can improve results quickly. Click To TweetThe results of this pilot clearly show that there is great potential in enhancing our decision making process with machine learning and data analysis.

We are not at the point where we’re ready to let a machine determine our investment strategies on its own- the way machines already do some forms of investing without human inputs.

Unlike an investor in securities, or a high-frequency bond trader, an accelerator’s main advantages are as a first mover. We invest in companies that don’t exist yet, have limited information on their markets, and have a limited history, or no history. So we invest in people – and people are inherently hard to quantify.

Our anecdotal experience of meeting teams in person *before* evaluating their applications, consistently reveals that the application process cannot identify many important personality traits. For an accelerator, success comes only when we are right about a trend, and a particular person, at just the right time.

So employing an AI powered decision-making approach cannot mean abandoning the unique advantages we have: the ability to see things others don’t see. Expertise (and hard work) is still the core of sound early-stage investing, but AI can help us to focus that expertise on the “creme de la creme” of potential investments.

It can save us from becoming jaded by the junk applications that routinely swamp our inboxes.

A startup is not an individual, it’s a team. And it is not in our interest to arbitrarily eliminate applicants who are not good at writing applications, or have other deficiencies more visible on an application than in real life. However, it is in our interest to conserve and spend our resources (including our time and energy), where the potential for gain is highest.

This approach can benefit higher-dollar investors too: later stage investors have many of the same problems accelerators have, but on a different scale. A Seed or Series A investor makes decisions involving 10-50x more money than any single investment from an accelerator, and they also receive more requests, on average, than a small accelerator does.

Currently the most obvious and most immediate advantage of using Decissio’s AI is for very early stage investors with many applicants, such as government innovation programs, and big accelerators like TechStars, Y-Combinator, and 500 Startups.

Tl;dr:

- StartupYard alum Decissio analyzed our past applications over a 6 year period.

- Decissio used this data and their own AI to predict which applications to StartupYard would succeed.

- Two of their top 10 picks were also StartupYard finalists

- They accurately predicted the bottom ranked half of applicants.

- This approach can be used by accelerators to:

- Improve applications overall

- Save time on the poorest applications

- Reduce systemic biases

- Get better information on applicants

- Decissio’s AI could be applied to other early stage investors, such as Series A and Seed Investors, or to large accelerators, particularly Tech Stars, Y-C, and 500 Startups.

- At the end of the day, AI will help early-stage investors to get better information, and spend more time focusing on the human-focused side of their work.