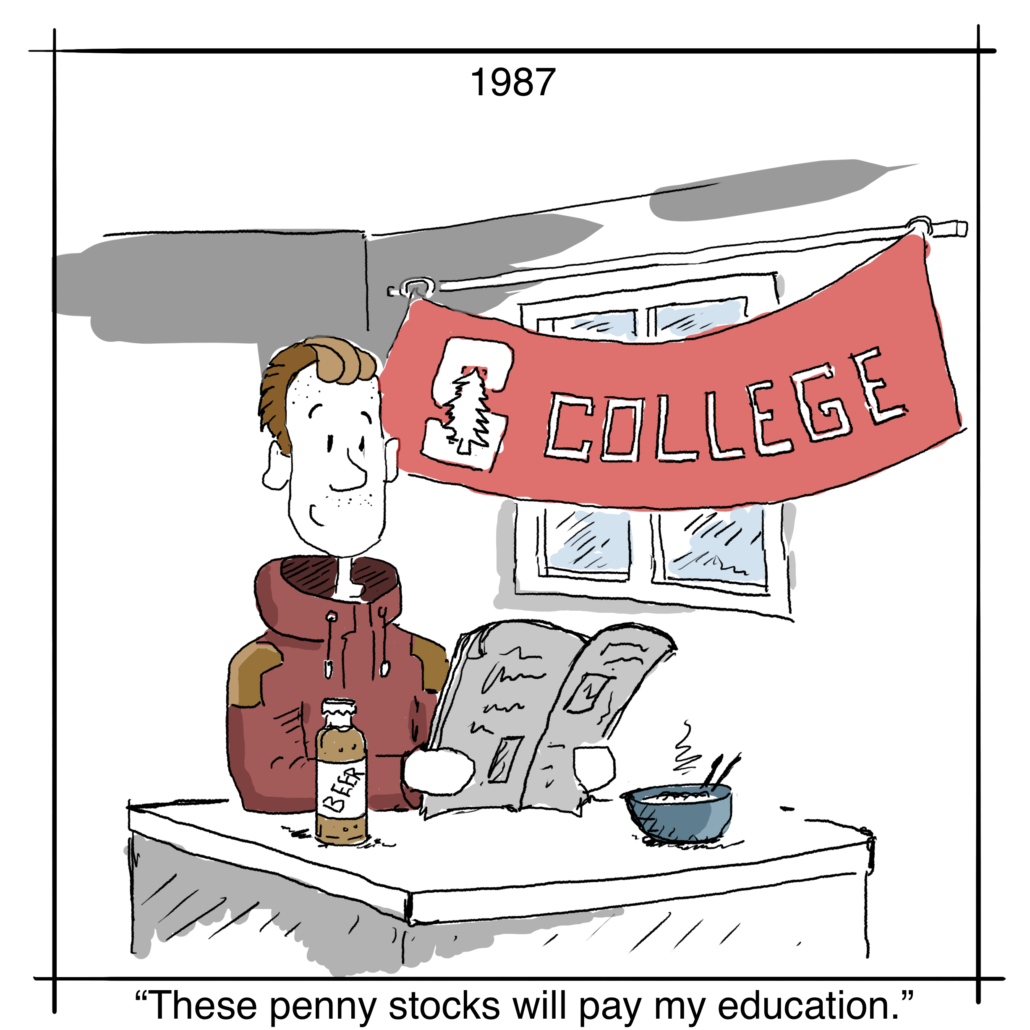

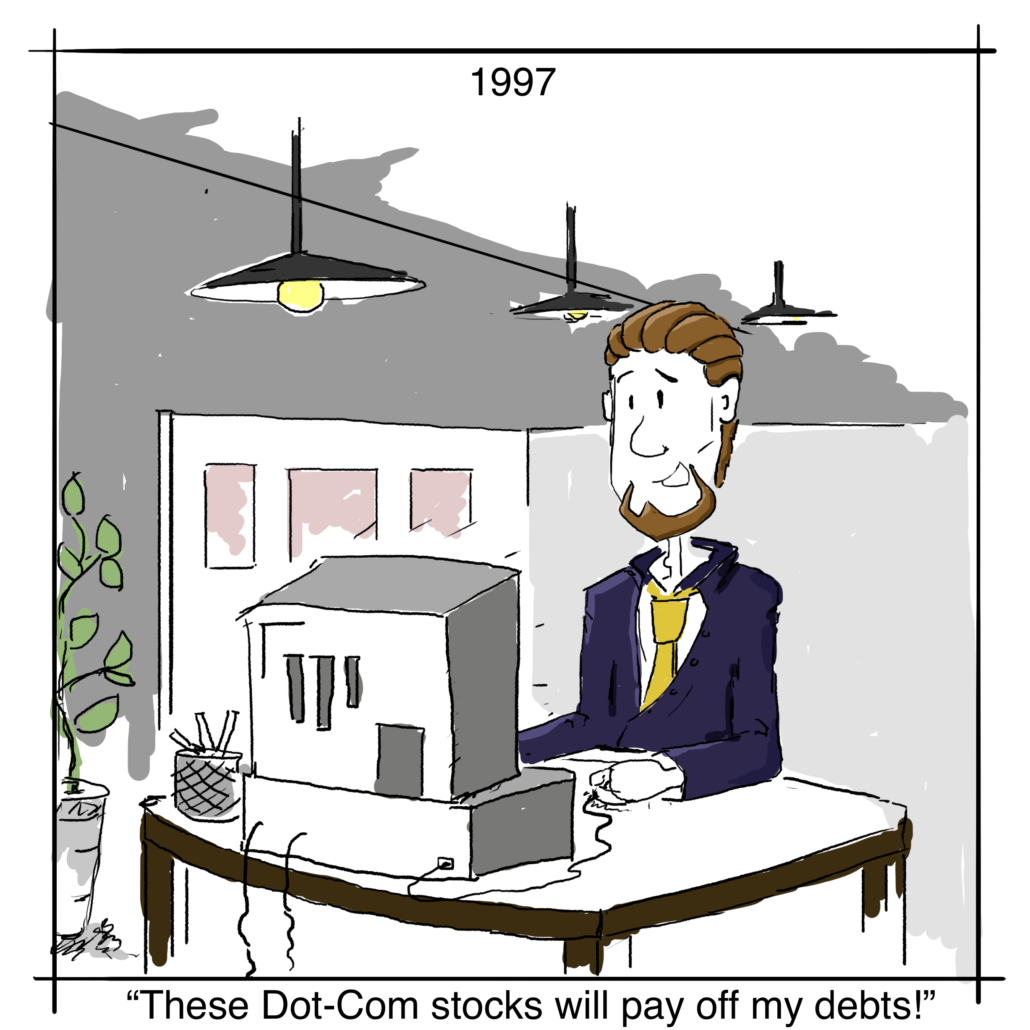

It seems like the tech investment market hasn’t been this excited about anything since 1999. The ICO, or “Initial Coin Offering,” is on the lips of every investor, and floats to the top of every startup discussion around fundraising and new business models.

Depending on who you ask, it’s a revolutionary shift in the investment paradigm that will help tech companies and investors alike become wildly rich, or it’s a scary bubble-creating, fraud enabling monster the likes of which hasn’t been seen since the dot-com bubble.

So what’s going on? What’s an ICO? What do you need to know about them? Why should I be wary or excited? This post will jump into the circumstances that created the phenomenon of ICOs, and try to dispel or confirm some of the most important common beliefs about them.

First, a bit of history:

First There Was Blockchain

In the distant technological past, around 2009, an idea emerged from a mysterious coder with the pseudonym of Satoshi Nakamoto. In a now-legendary whitepaper, he produced a theoretical model for a new kind of digital currency: what he called Bitcoin.

Without getting too deep into the technology, the key to Nakamoto’s innovation was the idea of a distributed digital currency that relied on a network of computers to process and authenticate transactions for its users. This network would create many copies of a “blockchain ledger,” and would copy transactions written to the ledger based on consensus with the network.

The ledger would contain many “coins,” or unique pieces of code that could be “traded” from one user to another only with the use of a private key. Over time, the system itself was designed to create more coins as a reward for those who processed transactions- a process called “mining.”

In this system, transactions would be theoretically tamper-proof. The system would keep what amounts to a never-ending record of everything it does, impossible for one person to alter alone.

Though Bitcoin’s exact origins and Nakamoto himself are mysterious, what is true today is that millions of people around the world have traded bitcoins, and used them for a variety of purposes, including making payments, transferring money abroad, and in some cases, illegal activities such as extortion, money laundering, and black market sales. There is such ongoing demand for bitcoins, that they have been valued by some exchanges at up to $5000 dollars recently.

The popularity of Bitcoin has spawned many follow-ups, including and especially Ethereum, which has presented a number of technical advancements to solve limitations in the original Bitcoin technology, particularly Bitcoin’s lack of speed and extensibility.

Today, the Ethereum blockchain functions as a platform upon which applications that need a distributed blockchain can be built. The Ethereum coin called “ether,” can be “spent” as a way of leveraging the network on which it runs to accomplish new tasks in a secure way.

Blockchain and ICOs

While Bitcoin popularized shared ledgers, new platforms like Ethereum promise to put that technology to much broader use, such as in authenticating contracts, securing communications, and enabling new forms of crowdfunding. Proponents see Ethereum and similar technologies as a way to decentralize many functions of the web, and eventually the whole economy.

TechCrunch has a good introductory article on some of those ideas. I suggest you read that as well.

An ICO is one of those new uses of a shared ledger. As simply as possible, it is the process of offering a new set of coins for purchase, either for cash, or more commonly, in exchange for cryptocurrencies that the seller of the coin can then exchange for cash, or something else. The coins being sold by the company raising the IO should be tied to some external financial instrument or physical asset, such as a loan, a share of common stock, a security, or in some cases, “credit” towards the use of the products a company offers.

You may recognize this kind of transaction as essentially similar to the sale of a security or a debt. The main difference is that the sale is accomplished using a blockchain ledger, and the “coin” sits in place of a typical security instrument, such as a bond, or a note.

Thus, an ICO could be used to facilitate many existing business activities. It could be used to enable a group of lenders to pool their money, or it could be used by a startup to sell equity in itself. An ICO can also be used by an existing company to offer a way of buying its services (the same way mobile gaming companies sell tokens, gems or other items to their players to make in-game purchases).

The advantages of employing blockchain technology in these circumstances are the same as ever: increased security, transparency, and auditability. In short, ICOs can potentially offer a better or fairer way of doing things people mostly already do.

So Why is this So Crazy Popular?

Because it’s so easy to setup, and easy to use. The wild popularity of ICOs in the past 6 months or so is largely driven by the general investor hype around cryptocurrencies. As the prevalence of shared ledgers grows, it becomes ever easier to leverage them for novel purposes like an ICO.

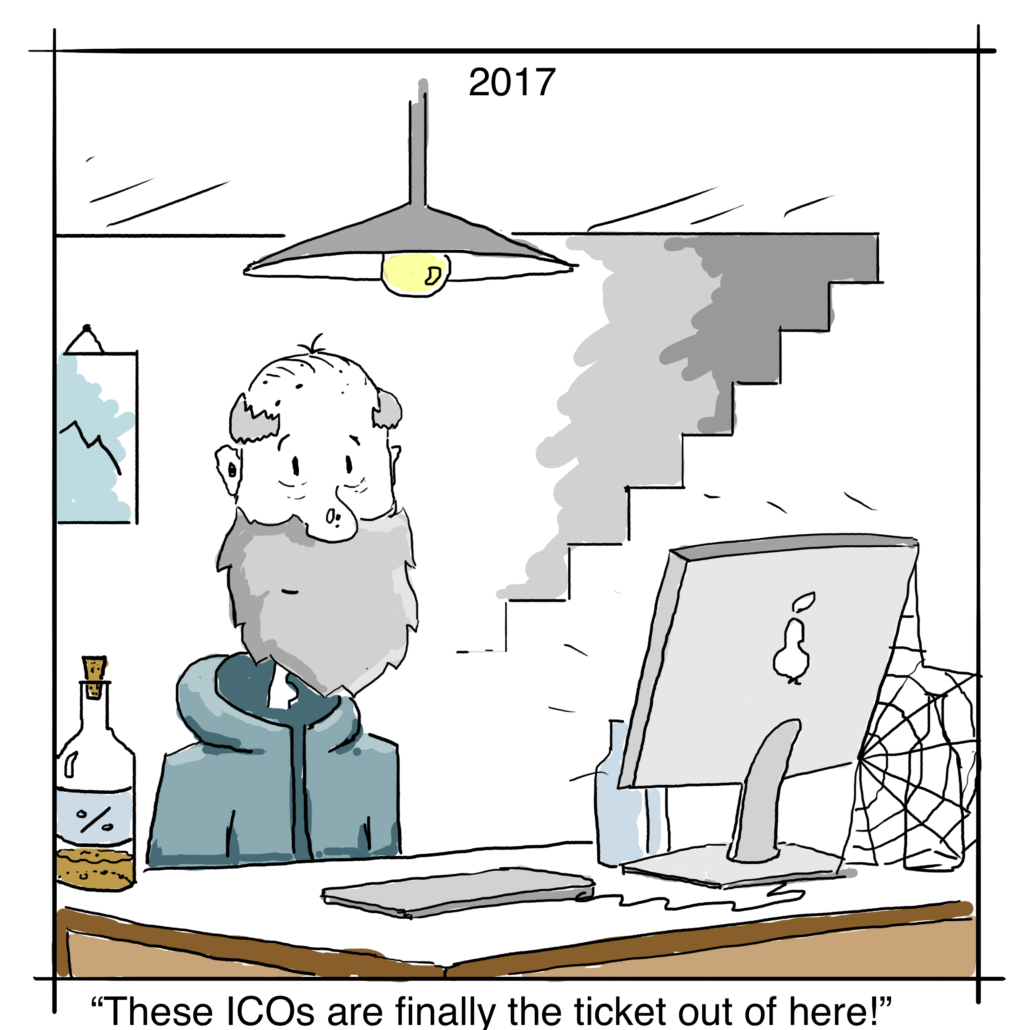

And that cutting-edgness can make the ICO market a bit frothy and potentially bubble prone. People who have invested in cryptocurrencies, and more importantly those who missed the huge easy gains that early Bitcoin and Ethereum investors made, now are seeking more opportunities to make returns of a similar scope. At least a part of this is mania and greed, as evidenced by the wacky valuations and amounts raised in some ICOs.

On the other hand, ICOs carry undeniably attractive advantages. They can be bought into from anywhere, by anyone, and are instantaneous- a powerful antidote to the slow and restricted nature of traditional investments and bank transactions for end-consumers. In a sense, an ICO lets individuals do what big investment banks have been able to do for decades: to be the first movers in new and exciting markets.

What an ICO is Not

Of course, that freedom and opportunity comes with its own cost.

Currently ICOs are mostly considered to be unregulated, and have thus been characterized as dangerous, risky for investors, and legally questionable by experts. Certainly those ICOs which mimic the characteristics of a classical IPO have been among the most concerning activity in the ICO market, and were the primary motivator for both the Chinese and US governments to intervene in the market recently.

An ICO can allow a company to bypass institutional investors who might normally help to diversify risk for consumers, or ensure that an investment is legally structured in a way that protects investors. In an ICO however, no central mediator such as a stock exchange or investment bank exists, and thus, in some cases, due diligence on behalf of investors is poor or non-existent.

Whatever the legal or ethical dangers, ICOs have quickly ballooned in value to what is estimated to be billions of U.S. dollars in the past year. Companies have used ICOs to raise eye-popping amounts of money, sometimes with little reliable information about where that money is going, and often with little legal protections in place for buyers.

ICOs have also been the tools of purely criminal enterprises, with a fraudster reportedly caught attempting to move $350 million of ICO investments offshore from India, after a fake ICO for a company calling itself OneCoin.

Massive speculation in cryptocurrencies has fueled plenty of fraud and abuse from bad actors looking to make easy money. And the distributed nature of a shared ledger makes it correspondingly difficult for investors to organize in response to problems. Collective shareholder action becomes difficult when many shareholders remain anonymous.

As to whether we are in a crypto bubble, as many commentators fear, it is inherently difficult to recognize a bubble when you are in it. But according to the economic historian Michael Lewis (author of The Big Short), a defining feature of the investor mania that leads to bubbles is “ an exponential increase in the volume and complexity of fraud.” And fraud today in crypto-currencies is both voluminous and increasingly complex.

Original Art by Mirek Sultz Copyright 2017, StartupYard

Are ICOs Legal?

At least right now, they’re not illegal in most places. But the question of their legality is part of an evolving situation. They have recently been banned in China, as the government grew concerned over the disruption they were causing in the country’s traditional financial markets. In addition, the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission of the US), has also issued new guidance suggesting that ICOs that are similar to a classical IPO must register with the SEC, and adhere to existing regulations.

The ESMA (the European SEC), has yet to issue coherent regulatory guidance for European investors and companies. European regulators are typically slower to act than either the US or China.

In addition to this, while an ICO might not be illegal, it may in some cases be technically illegal to participate in it. For example, investors who are American citizens, and the companies they buy coins from, may be at risk of violating US laws including FATCA and FBAR – laws that require many financial transactions to be reported to the US Government when they involve American citizens.

In most countries, ignorance of such laws is not a defense for breaking them.

Are ICO’s Safe?

They can be. An ICO is not inherently safe as an investment. One unique risk in blockchain transactions, as opposed to traditional commerce, is that nothing is reversible. “No backsies,” meaning that you can’t appeal to anyone to recall a transaction once you make it.

And a coin alone does not guarantee shareholder rights or ownership of something. However, if the proper legal framework is used to tie coins to real assets or give their holders certain rights, then an ICO investment or a coin purchase is not fundamentally different from the purchase of any other type of security or medium of exchange.

So while an ICO is not by definition “safe,” it is not necessarily any more dangerous than any other type of transaction. And in some ways, it can be considered more secure against certain threats.

Ok, but Should I Buy Into an ICO?

According to our in-house blockchain expert, Decissio founder Dite Gashi, you should not consider investing in any debt or equity ICO unless it meets some essential criteria (many of it the same as for any traditional investment).

Here are the highlights of Decissio’s checklist:

- The ICO’s Focus – The focus should be on the business, and not on providing investor returns, particular fast investor returns. If it looks like a pyramid scheme, assume it is.

- Meeting Technical Due Diligence – either you or someone you trust has examined the technical specifications of the offering, and are satisfied that it is sound from a technical point of view.

- Complete Company Documentation – Just as with any investment, the company launching an ICO should be on a sound legal footing, and should be represented by qualified board-members, free of legal trouble, compliant with regulations, and have its finances in proper order. If documentation that establishes this is not provided, then the investment may not be as safe as you think.

- An Exit Plan – A company raising money through an equity or debt ICO should have a clear idea of how and when investors can be paid back, what triggers a liquidity event, what events or milestones call for a reorganization of the company, and so forth. This should all be provided in writing and vetted by your own legal counsel.

- Legal Framework – Purchase of a coin in a debt or equity swap absolutely must have legal documentation tying the coin to a real asset, or to the right to collect payment on a debt. Sufficient collateral for such a transaction should be in place, and all standard legal documentation must be provided. The blockchain technology does not replace any of this, or make any of it less necessary.

To be clear: we are not offering financial advice. But our opinion is that an investor should make a habit of looking for the same kinds of things in any investment they make. The way that an investment is offered doesn’t change the fundamentals of wise investing.

As the renowned VC Fred Wilson says: “Don’t be greedy.”

Should I Raise an ICO as a Startup?

In answer to this, we would pose a different question: what are the specific advantages of doing an ICO?

- It’s Faster: ICO might be easier to manage in the long term. Because it’s handled using a shared ledger, there’s no need to deal with many investors all trying to give you money at the same time- no problems with exchange rates, transfer fees, bank delays, and other annoyances.

- It’s more Scalable: Unlike a typical early-stage investment, an ICO can in theory be easily extended or replicated in the future without any changes to existing agreements. Traditional equity investing involves complex time-intensive processes to transfer shares, convert notes, gather signatures, and the rest.

- It’s Auditable: A nice thing about an ICO is that it can all be audited. Investors can feel more secure because a company cannot easily lie about how much money it has raised, or at what value. It’s all in the ledger.

- It’s Flexible: an ICO can be used by a small group of investors, just as it can a large one. This means that you can theoretically offer early investors the advantages of using a shared ledger, without sacrificing the personal touch that is so important with early stage investments. Startups rarely just need money: they usually need investors who can help them. It’s still possible to do that with an ICO.

ICOs are a Threat to Traditional Investors

It should be obvious by now that blockchain technology and ICOs are perceived as a threat by many traditional investors. And with good reason. Traditional startup investors may offer more than just money, but money is certainly a huge part of what they offer. ICOs can be a way to get around large institutional investors and deal with people on a peer-to-peer basis, meaning that traditional investors will have to compete harder for investments, and offer more to companies they invest in.

Early stage investors like StartupYard also face challenges from this technology. As it becomes easier to get capital from anywhere, startups are perhaps less likely to think of an accelerator as a starting point for their business. They may find that raising money in an ICO is easier – maybe even too easy.

Investors down the line may also find that investing through traditional institutions doesn’t give them the access to deal flow that they want, and they could be attracted to ICOs as a way of getting “closer to the action,” and giving money directly to exciting startups.

Tech Business Angels and VCs may also find that startups are not as keen to cooperate with them because of the alternatives available. That may be good for some startups, and very bad for others. Small companies that raise money too quickly often make big, costly mistakes, rather than little, cheap ones. Institutional investors don’t make you immune to that problem either, but they can enforce much needed discipline on founders who are playing with lots of funds for the first time.

What can we do about it?

As the famous line from newspaperman Horace Greeley says: “Go West, young man, go West.” In other words: we must adapt to our times. The reality is that this technology is gaining popularity because it promises something that people want: a new level of transparency and immediacy, for investors and for startups, that the old investment world can’t match.

While we have to continue to advocate for the processes that have made us successful at what we do (which have less to do with money) we also have to recognize that the modes of technology change whether we want them to or not. Our model must adapt, which is one of the reasons that StartupYard has made itself available to smaller investors through private equity placements over the past two years. We see that small investors want more access to early stage investments, so we must provide it in a way that makes sense for us, and for them.

Still, and it bears repeating: startups don’t really need money as much as they need help. Really effective startup investors provide enough money, in order to offer the level of help a startup really needs. A day may soon come when StartupYard will adopt blockchain technology in our own fundraising efforts. But when the winds of change blow, you shouldn’t be blown away by them. At the end of the day: the tech business has to be about more than money.