What Launching 15 Startups has taught me about “Design Grammar”

“That’s the same homepage everyone has. It’s boring.”

I hear this quite a bit. As our first month of mentoring for StartupYard 2015 rolls along, we have 7 companies preparing to soft-launch their services and products, mostly with new branding, and some with entirely new names, over the next few weeks.

And we have this kind of conversation a lot. As they pick a name and take their first stabs at branding themselves, most of our startups suddenly become ambitious about their marketing language, site design, and logos. I love to see it, really, because it’s a sign of keenness to be bigger, better, and newer than the competition.

As they’ve all been working on their positioning statements for the past few weeks, and have gotten more comfortable with their value propositions, their go to market strategies, and their growth predictions, our startups start to feel that they’re experts on their own brands. As they hear more about calls to action, marketing campaigns, and branding generally, they start to get the itch to experiment with their own theories about their would be customers.

I find myself, on the other hand, being constantly discouraging; constantly talking about “consistent visual grammar,” and the “grammar of your design.” This often elicits blank stares of incredulity. What is “design grammar?” And why do we need that? Our Executive-in-Residence Philip Staehelin suggested to me earlier this week that I write a blog post to try and explain. This is that blog post.

The Great Sameness

A big part of this settling-in process is our startups exploring the branding of their competitors. They browse websites and check pricing and features, and they get used to what the market is focused on, looking for their edge. Our mentors also suggest competitors and potential partners they should look at, and the startups get very well versed in their market.

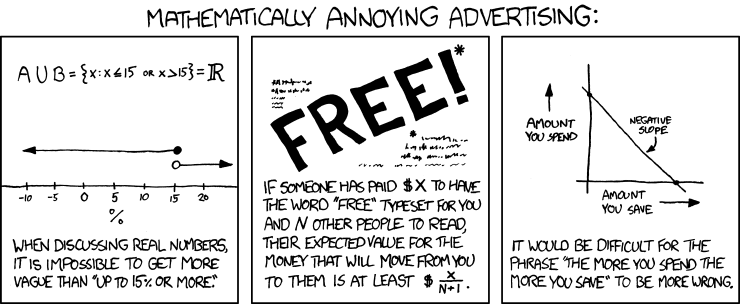

And then, it all gets a bit boring. We have a startup that is working on a competitor to Shopify or Volution, for example. Check out those two sites, and you won’t be surprised by what you find. Some variation in the choices of headers, a different call to action: “start for free,” instead of “get started,” or “get started now,” or one of 10 other possible variations. On the surface, they’re much the same.

Whether it’s B2B or B2C, a SaaS or a consultancy, the web has been taken over by a sameness in the way online companies communicate through their websites. Why is that? And why would that be a good thing?

Boring is not Boring

The answer is not sexy. As VWO points out, it’s because landing page design is more science than art. Companies with huge volume in SaaS products, like MailChimp, Mint, Shopify, Slack, and Dropbox, all use essentially the same layout for their homepages, and similar layouts for campaign landing pages. These pages have been tested, tweaked, and perfected using the collected data of tens of millions of visits to similar sites.

Companies with high inbound traffic pay expensive consultants, or use tools like Attensee or Optimizely, to collect fairly precise data on exactly how each piece of text, each image, and each particular call to action performs best- and they have the ability to tweak the site’s appearance for different regions, and even different types of users, to maximize the site’s conversion rate.

We seem to be arriving at a sort of paradox. We know, scientifically, which sorts of things work (or at least don’t fail) on landing pages and home pages, but that makes a lot of these sorts of pages look the same. Boring and safe is the rule. So their boringness, seemingly, would mean that they wouldn’t do as well as they do, because they’re not special. And yet, if they didn’t perform well, they would be changed. So what’s the deal?

Impress Me, but Don’t Surprise Me

This sort of thinking is the sort of thing that many startups struggle with early on. They begin to believe that “different,” and “surprising” are the same as “good,” and “effective.”

A sales director I worked with early in my career gave me a sound piece of advice that I’ve always remembered. He said this:

“If I asked you to show me 4 fingers, what would do?”

I held up 4 fingers on one hand.

“What if you held up two fingers on each hand?”

I hadn’t thought of it.

“Wouldn’t that be weird? When your customer gives you their attention, like clicking on your website or signing up for a newsletter, they are usually asking for information. They are not asking to be surprised. They are asking to be persuaded.”

There are many ways to hold up 4 fingers. However, his point was that doing something a customer doesn’t expect, even if it *is* surprising and impressive, is not necessarily going to make them trust you, or buy from you.

A “surprising” website, with a novel design and fancy layout, may make an impression on your prospect. But that impression is as likely to be: “this company is clearly good at making impressive websites,” as it is: “I trust this company to do whatever it is they are trying to sell me.”

Holding up two fingers on each hand might make someone think. But it might make someone think: “this guy is an asshole.”

Rather, “impressiveness” that translates to someone actually buying your product, is found in your descriptions and demonstrations of the product itself. The product should be impressive. The way you talk about the product should be in view of that impressiveness.

If you have a product market fit, then your marketing of your products should get out of the way as fast as possible. And the best and easiest method of getting out of the way, is using a visual design, a way of doing things, a “grammar,” that your prospective customer is likely to be familiar with.

Wanting a “creative,” and “different” website is natural. You want to be different. But “being different” about the way you present your products -if they are good products that the customers actually want to buy- is usually going to be a waste of your, and more importantly, the customer’s time.

Think about it. When you walk into a car dealership, you look around for the person who can answer your questions about the car. You expect that person to be in a suit, maybe with a nametag, so that you can recognize him or her easily. If someone came up to you in cutoff jeans and a bolo hat, smoking a cigar, you’d certainly remember that. But would you want to buy a car from them?

My guess is no. Because you didn’t come into the shop to appreciate a creative salesman. You came into the shop to appreciate and learn about a car you’d like to buy. The salesman wears a suit because he doesn’t want to distract you from doing exactly what you want to do anyway.

That is where the sameness of design comes from. As products get better, more specialized, and more powerful, the trappings of how we talk about them, and how we present them online actually get more straightforward. As we are all more comfortable with the ideas and the types of products we are discussing, the need for bells and whistles slowly diminishes.

A Mature Market Means a Shorter Sales Cycle

My father once took me with him to buy a car, when I was a little boy. This was in the early 90s. The salesman called the morning of the visit, and we spent hours talking with him about the cars my father was looking at. He took us to lunch, and on a drive in the car my father wanted to buy. They went through pages of options for the car, discussing all of them. They haggled some more, and they had coffee. They discussed financing. We spent 6 hours at the dealership.

This year, 25 years later, I bought the first car I could call my own, for my own family. The saleswoman was pleasant, and offered me coffee. The meeting took less than an hour, including the test drive.

Why? Because I had spent time at home configuring the car I wanted to buy on the company’s website. I had printed out the options I wanted, so when I got there, the deal was practically done already. She gave me a few pieces of advice, trying to upsell me on a few items. That was about it.

A car salesmen of a century ago would have been expected to take their clients to dinner, visit their homes, and work a sale for days or weeks. That was done because customers weren’t familiar yet with what they were buying. Trust in the dealer translated to trust in the product. But today, a Google search is a click away. Trust is statistical; scientific.

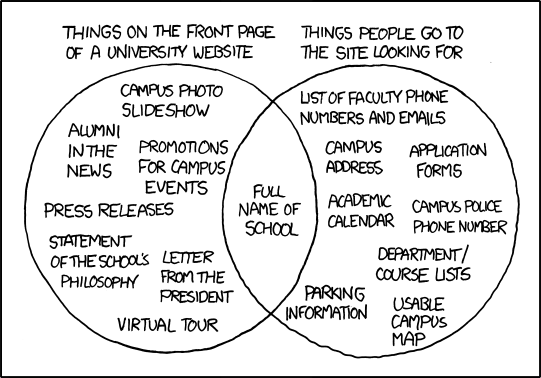

The web has followed a similar evolution: today, people expect the sales cycle to be short, and they’ll punish you for making them jump through any hoops. Every step between the customer and the content, or between the customer and the purchase, is a step that some customers would rather skip, and a step that is likely to diminish trust, rather than enhance it.

Clean and Frictionless are Two Separate Qualities

In our last cohort, one of our startups showed me a landing page that was nothing but an image, and a headline with a provocative question. It was something like: “Do you believe in True Love?” There were two large buttons: Yes, and No.

“Ok…” I said. “And now what?”

“Well,” the founder said, “It inspires you to click on it to give your answer.”

“Ok,” I said. And I clicked “no.”

Another text appeared: “Are you sure?”

:Facepalm:

I got what he was trying to do. Our generation has been raised on a diet of “interactive,” that promotes the idea of interaction without actual engagement with anything. It’s a ploy. Like having a popup in a video game that says: “press X repeatedly.”

But at least in a video game, the designer would be trying to trick you into feeling like you’re having fun after you’ve bought the game. We can tolerate trickery of this kind. It’s expected, and we’re already invested in the product. But for a landing page?

First, the visitor has already clicked a link or entered a URL to get to the site. That’s 1 action. Now they’re being presented with an “activating” action that doesn’t accomplish anything they haven’t already decided to do.

Would the prospective user be much more likely to download the app or buy the product after being activated twice? Not likely. Would the person who clicked “yes,” then be significantly more likely to download the app, than that same person would have been, if they had not been “activated” in this way? I don’t think so. And there would be no way to test it anyway.

Second, this sort of landing page is a conceit that people recognize for what it is. But whereas we’ll accept this kind of trick in a video game as part of the experience, a landing page has no “buy-in” from a visitor that ensures they’ll put up with your nonsense. They would have to click to get to the site, then click “yes,” and only then would you even get a chance to persuade them to buy or look at or download something.

That’s like making your prospective car buyer pay for a test drive. Only a highly motivated buyer would bother. I told the founder that if he did that, he could expect a >50% bounce rate on the landing page, and no positive effect on the bounce rate for the homepage it was linking to.

He launched the page and payed for Facebook ads, and the bounce rate was high as I had predicted, with no effect on the download rate for users who passed the first design hurdle. So he took the page down, and let users go right to the homepage. Lesson learned.

From Design to Content

Design in any mature medium, over time, becomes less baroque. Less “unique” in broad strokes. People learn what works. Everything gets to be more shorthand, and conventional. Gone are the salad days of edgy web design, with MySpace pages and GeoCities domains, replaced by white space, edge to edge. The new watchword for web design best practices is “clean,” not “shiny.”

Take a look at a prime example of an historically “edgy,” homepage, that has become progressively more conservative over the years. There’s a good chance you’ve visited. It’s Apple.com.

Do you sense a trend here? Discounting its first few iterations, which reflected the lack of clear web design principles in the age of GeoCities (and clearly before Apple considered e-sales to be vital to its strategy), the site had a “brochure” layout that was common in its time. The first web designers were, after all, magazine and textbook publishers, and those design principles migrated from the older media.

What’s interesting is when Apple introduces, around the time of the release of OSX, an “OSX Skin” for its websites. Here, the company is clearly trying to impress the visitor with the overall visual appeal of its operating system: a taste of what you’ll get when you buy a Mac.

In today’s terms, then, this would be like turning the Apple homepage into the screen of an Apple Watch or a mockup of iOS, and making the visitor navigate the operating system, to see how impressive it is. Surprising, yes. But would that be a boon to sales?

As we push forward in time, Apple stubbornly sticks to its “Mac Os” skinned visual design, but the design departs further and further from the actual contemporary operating system. The design settles, starting in the late 2000s, into a hybrid of the magazine and top margin button layout that we’re all familiar with. It’s sleek, it’s Apple, but it’s also ordinary. You know it when you see it.

While we can be sure that Apple actually had a hand in making this the prototypical design for most tech company homepages, we also see that once it’s set in place, it dithers less and less, and experiments become less frequent. We have found something that consistently works. The design has become the background. Our focus is on the content of the pages.

Design is the Background: Content is Everything

As our experience of the web has fragmented between tablets, mobile, browsers, apps, Social Media platforms like Facebook, the individual “design islands,” that used to constitute individual websites, have become more and more difficult to distinguish.

Publishing platforms like Medium or even Wikipedia do away with as much design as is possible, leaving only room for the content they contain to be found, catalogued, and displayed.

So, “impressive” design has become anathema to the web experience, as the quality and volume of the content available on the web has increased. We don’t want people looking at our websites anymore. We want them going straight to our content and products.

Because unlike 15 years ago, our content and our products can sell themselves; people are familiar with the notion of online business, and they don’t need to be reassured, they need to be given frictionless access.

The web has transformed from a “global village,” of boutique shops, to an expo, where everyone has essentially the same amount of space to display their wares: and the quality of their offerings determines everything.

That fragmentation and decentralization away from home pages can be seen in many places- particularly in SaaS products. How many people who use Dropbox actually go to Dropbox.com?

Instead, Dropbox has made itself integral to many of the things people do all over the web. Likewise for Twitter. I doubt that many web services 10 years ago would have imagined that they could activate and maintain customers, for years, without those customers having to bother ever visiting their websites.

Increasingly, traffic and eyeballs are concentrated on a handful of central platforms like Facebook, Google, or Reddit, from which the majority of readers browse the content of other pages.

This is becoming true of e-commerce as well, with e-shops being migrated directly onto Facebook. There may come a day when launching a successful SaaS will not even require a dedicated website. That day may be sooner than you think.

Why This Makes Design More Important

You may have concluded by now that I mean to suggest that the grammar of your of your site design, your product design, and your marketing are becoming less important. On the contrary. As users become more and more fluent in up-to-date principles of web design, they become attuned to deviations from the norm.

That attunement can be to your detriment if your design is sloppy or jarring. Or you can turn it to your advantage, by trusting your site visitors to follow clear, consistent, and focused visual and messaging cues. Trading flash for subtlety is just the first step.