The “We” Problem

As we welcome our 2016 startups this week, I get to do one of the scarier and more rewarding parts of my job at StartupYard, and that’s helping these companies define themselves, their products, and their customers.

When startups are getting ready to launch, they tend to be very focused on “what type of company” they want to be. That’s normal, and healthy. And it feeds into their ideas about what their “brand” should be, and how they should express that.

And here is where many startups stumble at the beginning. They don’t fully appreciate who their messaging is really for (clue: it isn’t for them), and what it’s really supposed to accomplish.

Where Brands Come From

The word “brand,” comes from the 19th century American practice of burning a rancher’s insignia in the hide of a cow, or other livestock, before moving the livestock to a marketplace. This was done to discourage theft from the ranch, or during the drive season. The word comes from the Norse brandr, which means “to burn.”

The practice of maker’s marks and watermarks goes back thousands of years, all the way to at least the invention of currency in ancient Sumer. In all cases, the practice originated from a need to protect against fraud. A maker, manufacturer, or publisher had to find ways of making sure that customers knew the difference between their products, and fakes.

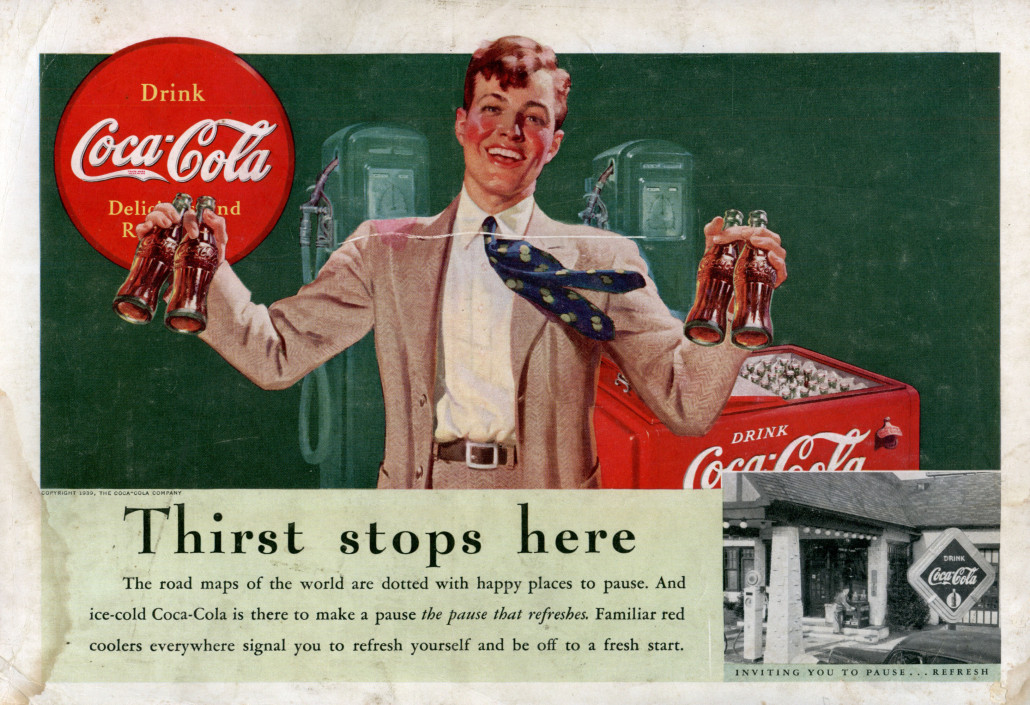

As the industrial revolution peaked at the end of the 19th century, it became common for manufacturers to “brand” all their products, usually on the packaging, to distinguish them from forgers or look-alike products, which were increasingly common, and threatened profits. It was then that the concept of a “trademark,” and the exclusive right to use a specific brand were introduced into the legal system.

In essence then, brands proliferated as a means of consumer protection. And in fact, that has not fundamentally changed. Brands are still, at the core, about helping people to make safe, fair buying decisions, and protecting them from fraud and danger.

Brands Are About Trust

It wasn’t long of course, before entrepreneurs realized that consumers recognized quality products by brand. And so they began to focus on the way their brands looked, and felt, to customers.

Manufacturers also rightly recognized that a trusted brand could convince people to buy new things from the same manufacturer. If you trust a company to make your radio, you’ll probably trust them to make your television as well. Sprawling conglomerations like General Electric and Samsung were compiled, based largely on this new realization.

Brands have become synonymous with design, with philosophy and politics, and with class, race and economic status. Today, people make statements with their brand choices. This can lead startups to forget that the chief aim of having a brand is not just building recognition, or fitting into a particular culture. It is about maintaining a level of trust with customers, that will follow them from one product to the next, or one year to the next.

The “We” Problem

Today, of course, we’re all very well aware of the effect that brands have on our thinking and behavior. We’re probably too aware of it. We’re told now that everything is a brand, and that every person can be a brand. This can get us off-track when it comes to communicating clearly with customers.

I recently worked with a startup that wanted to launch a new product, under a completely new brand. They needed help putting together their messaging, and writing copy for their homepage and other marketing materials.

At this point, when a company has a good product, knows its customers well, and wants to dive into the business of growth, is often where they stumble on what I began calling the “‘we’ problem.”

Simply, most of the copy they had written, and most of the messaging they were focusing on, was about them. To them, they were expressing the qualities of their brand. They were smart, they were hard working, they were trustworthy, they were friendly. So why shouldn’t customers want to buy from them?

Well, because customers buy solutions to their own problems. They don’t buy the work of your team, or the relationship you have with the product. Those things can be a plus, but they’re secondary to a buying decision.

The central questions you have to answer are these: Does the product do what I need? Am I the target audience for this?

People make their initial decisions based on that criteria, not on whether you communicate your attitude or your culture clearly.

Whenever I’m looking at copy for a homepage, I do a little experiment: I do a word search for the words “we,” and “us.” Then I compare that to words like “you,” and “our customers.” If you say “we” more than you say “you,” then you may have a messaging problem.

Startupyard.com, for example, contains 9 mentions of “we,” but 40 mentions of “you.” Also, several of the “we” mentions are directly followed by “you.” In addition, none of the “we” mentions are descriptive. They are active: “we’re looking for,” and “we try to.”

Most of the copy is concerned with either what kind of startup should join the accelerator, or what a startup will get by joining. These are the only two core criteria that matter in a decision to apply. “Does it do what I want?” And, “is it for me?”

Although it isn’t a rule that you can’t talk about yourself, you have to remain aware that to a prospect customer, how you see yourself is not that important. How you see them, how you value them, and what problems you will help them solve, are important.

Solve Problems, Make Emotional Use Cases

This is why we spend the first several weeks at StartupYard closely focused on one thing: the problem that the startup is solving for customers.

We work on positioning statements, which lead with who the customer is, and the problem being solved, and that is what initial conversations with mentors are all about. This helps the teams to stop talking about themselves, and start talking about their customers.

This also helps our startups to focus on emotional use cases. What frustrates customers? What aggravates them? What scares them? What brings them happiness? Saying “we have state of the art encryption,” is an unemotional argument. But saying: “Our state of the art encryption will protect you against hackers,” is a powerful motivator.

When Apple released the first edition of the iPod, it was famously “1000 songs in your pocket,” not “the next generation MP3 player, that can hold up to 4 GB.” This focus on the emotional use case: the feeling a customer gets from the promise of the product, is what makes Apple a powerhouse brand. It’s never about how smart they are, it’s about the experience you will get.

If you think your brand is about you, then you’re likely to focus on use cases that aren’t emotional for users, like efficiency, or price, or sophistication. In effect, you’re likely to make a feature argument, instead of a real value proposition.

It’s important to keep in mind what we talked about in the beginning. The primary purpose of a brand is to serve customers; to protect them from fraud and danger, by establishing a clear sign of quality. Only then can you leverage a brand to be something symbolic.

And that sign of quality can’t be forged. It has to be earned by solving customer’s problems- by offering them something they can clearly understand and want, and by delivering exactly what you’re offering.