The Positioning Statement: Finding a Window Into the Mind

Originally published on our blog way back in 2014, this post has been one of our most enduringly popular. According to Google Analytics, the average reader has spent over 20 minutes studying it. It is also our most popular piece on Medium. Since that time, we’ve shared this post with scores of startups, and used the methodology detailed here over and over again. This post is updated to reflect all that we’ve learned in the past 3+ years.

What is Positioning?

“Positioning” has often been described as “the organized system for finding a window in the mind.” That’s how Al Ries and Jack Trout described it in their book: Positioning, a Battle for Your Mind, a groundbreaking work from 1981.

Al Ries is often credited with coming up with the term “positioning,” and he describes it as a way of using a customer’s own experience of the world (including with other brands and products) as a way of communicating with that customer. Rather than communicate in a vacuum, companies that use effective positioning target customers who are already familiar with competing products and brands, and use that familiarity to differentiate themselves.

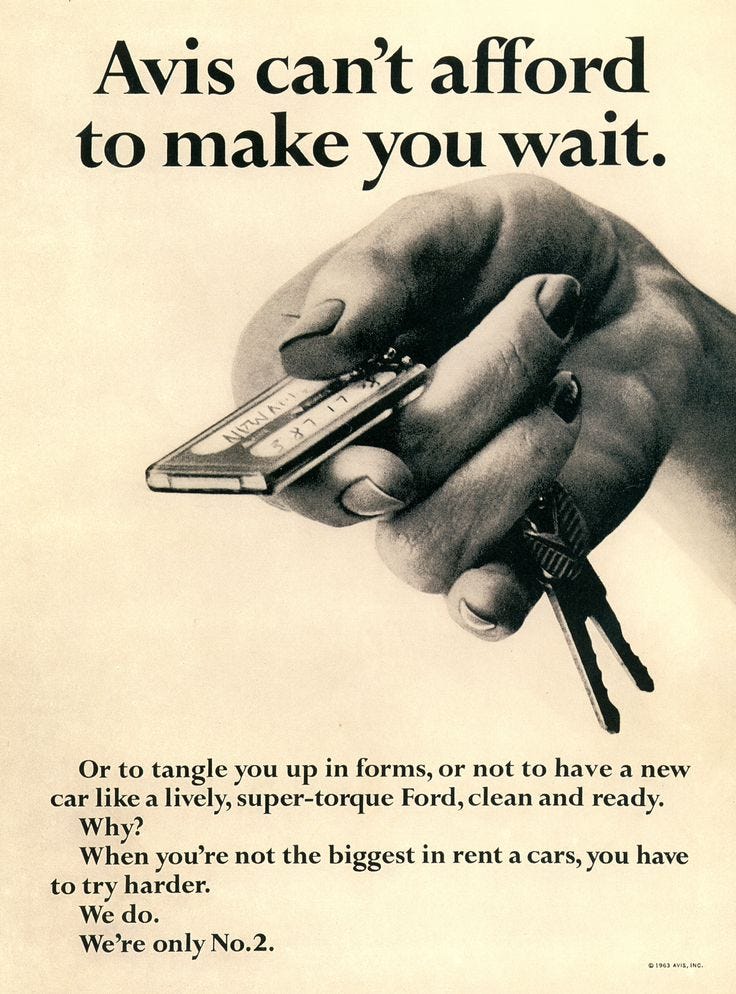

In the book, Ries highlights perhaps the most famous example of brand positioning in the 20th century: that of Avis, which in 1962 premiered the tagline: “At No. 2, We Try Harder.” Avis was at the time the market runner up in rental cars, and the company used that fact to imply that they were more accountable than their competitors, because they had to be.

In an early case of position-focused advertising, Avis used their status as 2nd in the market to imply that they were more attentive to their customers, because they had to be.

Positioning is Everywhere

When we stop to think about positioning as a promotional tool, we begin to see that it is everywhere.

Brands use their competitors as foils for their own messaging constantly. Remember those “I’m a PC, I’m a Mac” adverts.

Apple portrayed PC users as unstylish and bumbling in a popular series of TV spots.

Brands for the the past half century have often focused less on defining what their products are, and chosen rather to define what they are not. Another striking example comes from 7-up, which in the 1970’s sought to gain market share by telling customers that their clear soda was “the un-cola,” explicitly defining themselves as essentially “Not Coke.”

Whereas in the past, consumers may have seen their range of choice as: “drink Coke or don’t drink Coke,” 7-up presented a different scenario: “drink 7-up when you don’t want Coke.”

In presenting consumers with a new choice: either drink Coke or drink 7-up, the brand found a window into consumers’ minds. It suggested that there were many people who would prefer an alternative to Coke that was not available.

By framing 7-up as an alternative to a popular drink, the brand convinced retailers and consumers alike to buy 7-up along with Coke, in order to fill the demand implied by the advert. In 7-up’s ideal scenario, customers would not stop buying Coke, but would buy 7-up in addition to Coke.

The product itself also emphasized its differences from traditional sodas. It was not caffeinated, it was sour, and it mixed well with the more popular alcoholic drinks of the time, including gin and vodka, which were gaining market share in the 1970s. “7 and 7″ was a popular drink choice by 1970, a mix of Seagram’s 7 Crown Gin, and 7-up.

The brand thus further differentiated itself from Coke, which had traditionally focused its brand on taste and tradition, using the tagline “It’s the Real Thing.” Whereas Coke was a conservative choice, enjoyed by families and older generations, 7-up was a young brand- enjoyed at night in bars and in cocktails, rather than on sunny afternoons at baseball stadiums or at restaurants.

Thanks to these ads, 7-up rose in the 1970s to 3rd place among sodas, only losing its market share with the rise of diet sodas in the 1980s and 90s, and the decline in popularity of mixed drinks in favor of bottled drinks and beer.

What a Product Positioning Statement Looks Like

Here we’ll focus on a sub-discipline of positioning as a whole: Product Positioning. It’s the same general philosophy, but with its own specific methodology.

When a startup team joins StartupYard, one of the first things we ask them to do is to sit down and write our a “positioning statement.” The format is deceptively simple, and it looks like this:

Product Positioning Statement:

(Our Product) is for (target customers):

Who (have the following problem):

Our product is a (describe the product or solution):

That provides (cite the breakthrough capability):

Unlike (reference competition):

Our product/solution (describe the key point of competitive differentiation):

Why A Positioning Statement Is Important

The positioning statement contains the core elements not only of a product, but also of its marketing and sales strategy. And while most of our teams have worked primarily on ways of describing their ideas, a positioning statement does more than this: it also justifies the notion of that idea becoming a business.

It’s important for a startup to have the concepts of saleability and market differentiation baked into the essence of the product. Writing a positioning statement, like writing a SWOT analysis, can reveal basic strengths and weaknesses in a product while it is still in the “idea” phase.

A Starting Point

Even more importantly, a positioning statement can serve as the basis for validation of a product. If you can’t describe what your company does in this compact format, it’s possible that you aren’t sure yet what your company actually does. You may be sure of what you are doing on a technical level, but what that means in business terms might not yet be clear.

The positioning statement is a conversation starter, particularly with early mentors and core team members, to facilitate early discussions about core strategy, and how the team sees itself in the bigger picture, what market it is really addressing, and what its real competition is in that market.

And a positioning statement, well-executed, can be transformed virtually complete into the core marketing message for a product, once it is developed. Take this copy from Nest’s webpage:

“Our mission is to keep people comfortable in their homes while helping them save energy, and with the next-generation Nest Learning Thermostat, we’re able to spread that comfort and savings to even more homes — and to help higher-efficiency systems perform the way they were meant to.”

Here are all the elements of a positioning statement. If the Nest founders filled in our form, it would look something like this:

Our Product is

For: Upper-middle class and wealthy people

Who: Own homes and spend a lot of money on energy costs and heating/cooling systems

Our product is a: Smart Thermostat and related products

That provides: Savings and increased comfort by improving efficiency of existing systems.

Unlike: manufacturer provided systems

Our product/solution: Learns and intelligently adapts to the inhabitants to increase comfort at all times, while saving money

A Positioning Statement Tells the Truth

The above “translation” of the Nest positioning statement doesn’t say exactly what their marketing copy says of course. They don’t mention wealthy clientele for one thing. But at $130 for a smoke detector, and $250 for a thermostat, that is surely the market they are targeting.

Their products are priced high enough to be clearly exclusive, but low enough not to seem extravagant or make a money-wise customer feel foolish for purchasing. And anyway, that messaging is not only found in the price, but in mention of “homeowners,” and of “higher-efficiency systems.” These subtle cues indicate to customers that the product is made for people who value performance, and are willing to pay to get it.

Features ≠ Differentiation

Notice too that none of the positioning statement deals with the exact features of the product. It’s all about the outcomes the product promises.

This is key: their competitive differentiation is not on a feature-by-feature basis, but holistic. They frame their competition as not only out of date, but barely worth mentioning at all. They indicate that their competitors (the providers of the systems), are not even in the same business as they are, and that therefore competing products are not even worth comparing in a more granular way.

These are all elements of Nest’s marketing that are informed by the market segment they have chosen to address, from the quality of the products, to the design, to the sales language and the pricing. And so the marketing message that says: “this product is for you,” when speaking to its target client, is backed up by a product that is built with that person in mind. The mission is clear: this is not a product for anyone, but for someone very specific, so that when the customer comes across the product and thinks about buying it, he or she can immediately see that it is made for them.

Who, Not What

There’s a reason the positioning statement starts with “who.” Over the years, we’ve consistently observed that the first thing most startup founders do is try to talk about the product before talking about the customer.

But here’s why that’s a mistake, and why the positioning statement doesn’t do that: understanding the target market is the first hurdle in actually validating a new product. Features are a distant second consideration to clearly articulating who the customer is, and what their problem is.

A laundry list of features doesn’t really address the problem of “who” the product is for, but only “what” it is for. And that “what” that a feature describes doesn’t necessarily give any indication of what problem is being solved. Startups that are dealing with complex technologies can easily skip over the core user benefits of the technology, in favor of describing the technology itself.

Common is the startup that pitches “a revolutionary new method of transforming leavened wheat products into crispy squares by employing concentrated on-demand heat conduction derived from electrical coil technology,” instead of pitching: “toast whenever you need it,” or even “a less boring version of bread.”

People Buy Outcomes, Not Features

Customers ultimately buy solutions to their problems, not technical specifications. And those problems are not always the same as the ones that the feature list actually addresses.

Consider this, when thinking about buying a car, what are the first things you’re likely to check?

Probably it isn’t technical specifications. Most people will answer one of two ways: they will check either prices, or reviews.

That indicates that the customer is very aware of what their problem is. They need a car, and they need it at a certain price, or at a certain minimum level of comfort and safety, or both. Car companies rarely list their prices up front on their websites precisely because they know that this is what customers are looking for, and so they are able to ask for customer information in exchange for information on their pricing.

Cars rely heavily on marketing to differentiate themselves, but the marketing is typically not focused on what the cars actually do. And that’s because cars all pretty much do the same things. So the problem being solved for the customer is not “I need a car,” but “I need a car that fits my personality/lifestyle/class/status and/or specific needs.”

Look carefully at a car commercial, and you’ll be assaulted with subtle and unsubtle cues about price, lifestyle, class, education, and culture, but not much about fuel injection, or anti-lock brakes, or all-wheel drive. These things may get a mention, but the whole object is to present the car as being a great value, in consideration of all that it offers for the price being asked.

Lincoln’s famously ponderous commercials for town cars are definitely not focused on features.

The goal of a typical car commercial is to convince a customer that they are buying the status and the culture that is associated with the car; that their decision is not motivated by price, even when it usually is.

That is how powerful positioning is. By showing a very clear understanding of who their customers are, car companies can turn a price-motivated decision into a statement about who the customer is, and about their place in society as a whole.

Try this: go and ask someone why they bought the phone they own, or the car they drive, or the computer they use. Whatever it is, ask them why they chose it.

The majority of people you speak to will probably not say: “it’s the best I can afford.” Instead they were answer the question in terms of what the phone or car or computer represents to them; what it says about them and their values.

For example, if the person has a cheap phone, they’ll say something like: “I just use the one that came with the plan. I don’t need anything fancy.”

That’s often code for: “I’m too cheap to buy a nicer one.”

On the flip side, ask a latest model, hi-tech phone owner why they bought their tech toy, and they’ll say it’s because they value the design, the features, or the amazing convenience of using it. They won’t say: “I bought this because I want to signal that I am wealthy and can afford luxuries.”

This dedication to explaining our motivations in personal terms doesn’t extend only from a marketing strategy for high end consumer products – it derives from the way those products are made as well. The design and build of a product must subtly betray its role in social signaling for the owner. Cheap cars are “humble,” while super-expensive cars are “subtle.” It is the cars in between that are most ostentatious.

When you see a fancy paint job on a cheap little economy car, you cringe because it is a confused communication of values by the owner. It’s pig dressed as a lady.

Consumer products can also be designed to signal their utilitarian nature, in order to make customers more comfortable with their purchase. For every €20 bottle of wine, there is a €5 bottle of wine that looks somehow less pretentious, and more sensible.

The Position and the Pitch

The main difference between a positioning statement and a full blown pitch is that the positioning statement says in plain words, what is really true about who your product is for, and what you believe its market fit to be.

This will help you to stay away from visions of (and talk about) your product changing the world, even if it doesn’t really have the capacity or the capability to be a real world changing idea. Not all products have to be for everyone, and many of the best products aren’t.

It will also keep you honest and focused; force you to make clear the needs of the market you are targeting, and force you to live in their shoes instead of your own.