Don’t Be in the “Startup” Industry

This week, Cedric, our Managing Director, asked my opinion on an article that appeared on Medium last month by Arthur Attwell. Attwell shut down Paperight recently, and it’s an emotional post about some of the mistakes he thinks he’s made, but also on the industry he has chosen to inhabit. He’s not done with startups, but he’s done with “the startup thing.” The conferences, the competitions, the startup media, and the accompanying apparatus that is designed to funnel investor money through startups, into the hands of people in the know.

“What do you have to say to that? It reminds me of some of your opinions as well- maybe there’s an article there?” Indeed Cedric, there is an article there.

The Startup Industry

Attwell makes reference to the “startup industry.” That is the endless and sometimes bemusing list of events, conferences, competitions, breakfasts, lunches, brunches, innovation slams, hackathons, and every other possible flavor of sponsored, packaged, pre-digested infotainment that startups are sold as steps on the ladder to success.

My own feelings on this subject are mixed. I’ve been to a lot of conferences. Cedric’s are much stronger- maybe because I still feel I have a lot more to learn about the industry in general. But I often wonder what startups are doing there, particularly when they’ve already been funded, and when their customers are not the event’s audience.

Worse still can be pitching competitions, where again, startups are not necessarily pitching to an audience that is as interested in their products or them, as they are in seeing whether that person will fail on stage. Admittedly, I have rooted for startups to fail at pitching competitions, either because I didn’t like the idea, didn’t like the person, or for some other reason. I have never been inspired to help that startup achieve anything.

And while prizes are often involved in competitions, the terms involved in those prizes are rarely that attractive. A $500,000 “prize,” especially for a startup that can actually win that prize (meaning they’re good enough to beat up to a hundred others at the same competition), is not necessarily something that a good startup wants, particularly when there are better investment offers already in the offing.

At Slush 2014, for example, one of the finalists for the half-million euro prize stated flatly, when asked how he would use the prize money, that he wouldn’t take the prize, because the terms weren’t favorable enough, and he had better offers. That’s not that uncommon.

That’s the same sort of strange logic that Hollywood stars or famous musicians sometimes talk about: once you’re rich and successful, everyone wants to give you things for free. If you’re good enough to win a 6 figure pitch competition, you can probably land a far better private investment already. So what’s the game really about?

The TechCrunch Bump and the Trough of Sorrow

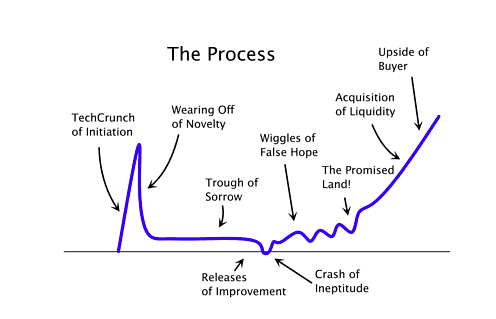

Andrew Chen famously wrote about the phenomenon of the TechCrunch Bump and the Trough of Sorrow. Namely, that the publicity associated with the “startup media” and acclaim in the “startup industry,” doesn’t actually translate to real success. It can help you land a few early investors, maybe, but it won’t actually make your product anything that your target users want to actually use, much less pay more. However, as Chen points out, far too many startup CEOs think that the name of the game is to become successful at being a startup, and so follow all the wrong signposts on the route to that goal.

Used for educational purposes: you can find the original at Andrewchen.co

And that route is expensive. There is unquestionably an industry of bells and whistles that is selling things to startups that they should, if they’re competent, confident, and energetic enough, never actually have to pay for.

The whole structure of startup conferences is weird. And the structure reveals the primary motivations. Conferences that charge startup founders to attend, while letting the press in for free, make it clear where their priorities lie, and it isn’t in helping startups.

While investor passes are often more expensive than entry-level tickets for entrepreneurs, the money is in up-selling the startups to tables, booths, and other “opportunities,” that are of questionable value, while the investor passes will in reality find their way into the hands of investors who get deep discounts off the sticker price.

If you are a non-funded startup struggling to survive, you should not have to pay to attend a startup conference. Full stop.

We Can Be a Part of the Problem

And we’re a part of this as well. Recently I was invited to speak at a local event where Startups from this region will pay up to 160 Euros to hear me and a list of interesting people speak. I know that part of what they’re paying for is the opportunity to meet me (and people like me), and pitch me their ideas. Which is a shame, because if any of those people emailed me, I would gladly meet with them for free.

All the truly valuable partners, investors, and friends of our organization that I’ve met and seen at conferences would do the same.

The thing is, I’m creating value for this event by being there, and making it possible for the organizers to profit from my presence without paying me- and the money is coming from startups who can probably ill-afford to waste money on hearing me talk about anything.

Meanwhile, I’m getting a lot of value out of this event for free. I’m speaking, which means I’m helping the StartupYard brand, and I’m getting a look at all the startups in attendance. I am the real customer for this event- everything has been tailored to suit my needs.

There’s the notion that you’ll “network,” at such events, and like Attwell, I’ve had limited success in doing this. If networking is about building relationships with people who have a common interest, then success would be defined by the number of working relationships that have come out of conferences. I have made a few of these, and I value them, so I credit the allure of conferences in allowing that to happen. It’s not a lost cause.

But again, the people who I’ve gone onto having a very productive relationship with from conferences were at the conferences looking for me, just like I was looking for them. So the conference was a *really* expensive way of meeting them, considering our shared interests.

I still see some value in a certain type of tech conference, particularly ones like this Sofia’s Bulgaria Web Summit, which is run by StartupYard Mentor Bogo Shopov. There, the startups paid a nominal fee, there was little window dressing, and the speakers were by and large not investors, but real thought leaders and passionate advocates for new types of ideas.

Likewise, I attended Howtoweb in Bucharest in 2014, and was delighted by the fact that the organizers brought mentors in to do actual mentoring with real startups- all of whom paid very little to attend. Mentors were not there for their own ego-stroking purposes, but to meet and engage with interesting young people. I loved it. So good conferences are certainly possible.

Things have also changed for the good in other ways. The famous flap over Demo, for example. In 2008, disgusted with Demo’s practice of charging startups up to $2500 to pitch their startups on stage at their popular events, TechCrunch founder Michael Arrington scheduled TechCrunch 50 at exactly the same time, and offered startups the opportunity to pitch for free. TechCrunch would charge investors to attend the event. One needn’t now ask which side won that argument- TechCrunch now possibly runs the biggest startup pitching events in the world.

The Moth Trap

Cedric describes the “startup industry” as a “moth trap.” You know those lamps that lure moths to them in order to zap the life out of them? That’s a bit harsh, but it can be accurate.

With so many attending startup events hoping to make breakthroughs with their startups in terms of investment, hiring, or partnerships, the expectation levels are often over-hyped. It takes a lot of work to turn even 2 or 3 contacts from a conference into something that might eventually move the needle at your startup. It takes a lot of false starts and false friends to find those people who are really going to make a difference for you.

Worse yet, startups show up at these conferences with unreal expectations about what they’re going to get out of it- to the point that they ignore real opportunities when they’re presented. I’ve talked to more than one interesting startup that has paid for a small space at a large conference, that has not been funded, and invited them just to apply to StartupYard, even if they don’t see themselves moving to Prague.

For an application that takes maybe an hour of a startup’s time, we offer the option of real funding, and a real direction for a young startup. Few apply, and the more they’ve paid to be a part of the conference, the less likely they are to apply. It’s as if when I mention that we offer funding and a program that’s designed to help them make real progress, they have been conditioned not to believe me.

It’s as if they think that because they have a few pieces of swag, t-shirts, and a rollup so that they look like a startup, and have had conversations with investors (and only conversations), that they would be taking a major step down to consider submitting themselves to anything resembling a reassessment of their priorities.

They have been conditioned to believe that their goal in life is to land a big funding round, and that giving up 10% of their company (which is worth exactly nothing until someone invests in it or it makes a profit), in exchange for real, tangible help in moving forward will be a hinderance when it comes to future negotiations, rather than a net gain.

As I’ve mentioned previously, and as has never failed to amaze me, I have heard from startup founders who have never raised money, that our terms are too steep, because “a VC told me that we could get a valuation of X Million Euros.” You could, if that VC invested in your startup. But they haven’t. And the notion that you’re going to get an investor at that valuation at a startup conference might be a little unrealistic.

In fact, I know a few VCs who might look down on the fact that you’ve paid for swag and a conference booth without signing a real live customer. These people are smart, and their job is making money. They will be looking at your traction, not your logo.

But still, the conference environment is like the California gold rush of 1849. The people who made money then weren’t the prospectors (the startups), by and large, though a few of them got filthy rich. The people who made the steady money in the gold rush were selling the shovels and the whiskey. Or in today’s terms, the metal water bottles and the keychains.

In that environment, we sometimes feel like the guys who walk around offering to lend the prospectors our heavy excavation equipment, and help them dig for gold, and being told that 10% of the loot is too high a price to ask, given what treasures might await. Keep shoveling.

Attwell blames himself for being a moth to that flame- falling for the adulation of the “TechCrunch Bump” rather than focusing on his startup. He’s right to blame himself, but he’s also right to blame the industry for perpetuating the myths it does in order to sell the show, and perpetuate its own legends.

Breakthroughs are not magic, and they don’t happen accidentally. And it was with not a little irony, I thought, that the speaker line-up for last year’s LeWeb conference in Paris was a parade of people who all said more or less the same thing, to the point of it being a sort of idée fixe for the whole conference: “this is not magic.”

There were more presentations about failure at LeWeb last year than there were about success- at least that was my impression at the time. There was an overtone of exasperation with the magical thinking that has been associated with startup culture in recent years, and this manifested as a pragmatic appeal to the people in the audience to be a little more grounded, and to understand their own limitations.

Summing it Up

In a brilliant essay, Paul Graham (of Y-Combinator) wrote last year about the problem of “startups,” with respect to our education system, and our business culture. He points out that education teaches young people to fulfill adult expectations, not to fulfill their own passions. Education and work is a game with rules, and can be won if you know how to game the system. In the same way, we teach young people to “do startups,” according to a paint-by-numbers system, rather than encouraging them to follow their passions in any way that might work: “It’s not surprising that after being trained for their whole lives to play such games, young founders’ first impulse on starting a startup is to try to figure out the tricks for winning at this new game.”

He goes on: “Since fundraising appears to be the measure of success for startups (another classic noob mistake), they always want to know what the tricks are for convincing investors. We tell them the best way to convince investors is to make a startup that’s actually doing well, meaning growing fast, and then simply tell investors so. Then they want to know what the tricks are for growing fast. And we have to tell them the best way to do that is simply to make something people want.”

We can see in this a horrifying regressive cycle. Successful startups all make the same “noob” mistakes that unsuccessful startups also make. Only when they become successful, the lessons of their failures are always forgotten. They had swag, so you have to have swag. They won disrupt, so you have to win disrupt.

Karl Marx once wrote of something said by Hegel: “all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice.” Marx comments: “He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

The axiom has often be applied to geopolitics or to cults of personality (Marx was applying it to Napoleon and his nephew Napoleon III). But it can as easily be applied to generational differences.

Every generation makes its own unique mistakes; generating its own unique tragedies. But there were reasons to make these mistakes- they were made in the process of trying to accomplish something new and different. The next generation repeats the same mistakes again, but this time only as a matter of form; only because that is what is expected of them, with no sense of the purpose behind them. Tragedy becomes farce.

That’s why we exist- just like Y-Combinator. That’s what keeps us relevant. Because at a good accelerator, and we try to be the best accelerator we possibly can be, with the best and most engaged mentors we can find, mistakes are things you learn from. And they don’t have be your mistakes- they can be someone else’s. They can be ours.

Failures are productive. We are here to make sure that our startups are not slaves to fashion, but are remaining true to themselves as they grow. That they are being realistic, and honest with themselves.

We naturally want to be like the people who we idealize as models for success. But people are very bad at recognizing what matters when it comes to repeating that success. So you get entrepreneurs who dress like Steve Jobs, or think that the habits and peculiarities of successful role models are the “trick” to being as successful as they were- rather than the more common sense reasons like hard work and some good luck.

You make life about becoming something, rather than accomplishing something, and no matter what else you teach people, they’ll focus on the appearance rather than the reality. In our attempts to be the things we think we need to be: “entrepreneur,” “startuper,” “winner,” we end up betraying the things we care about. Or worse- we don’t even pay attention to the things we actually care about, because they don’t have the caché necessary to turn us into something others will recognize and respect.

An unfortunate part of this business, and we’ve seen our share of this at StartupYard, is that many of us are pretenders. That’s not a bad thing. That’s nobody’s fault. A person can be a pretender, and find their true passion later, when they’ve exhausted themselves or gotten wise to the game and stopped playing it. That people pretend is a sign also that they are seeking something they recognize as valuable.

I would in fact posit that the existence of the StartupLand circus and the attendant conferences, seminars, events, and other time-wasters, is an indication that there are enough really passionate people circulating in the tech community to sustain such high numbers of pretenders and play-actors. If there wasn’t anything real, the whole thing would eventually collapse under its own weight. It still might, but at the core, I see more genuine innovation, energy, and passion now than I did when I started working with startups.

And while I see a self-adjustment in StartupLand may be in the air- a common feeling that the game has gotten old- I also see that most of the startups we work with recognize the real work that remains to be done.