Exponential Innovation: The Universal Basic Income

Why the end of traditional jobs is inevitable, and what we can do about it.

Why the end of traditional jobs is inevitable, and what we can do about it.

This is part of our ongoing series on Exponential Innovation. Check out other entries in the series:

The Universal Basic Income is a radical plan to remake the role of social welfare and work in modern society. In this post, we will discuss the philosophy of the UBI, its practical implications, and how it became a serious topic of discussion among many of the world’s leading economists, from all points on the political spectrum.

Already in the past century, the foundations of human industry have experienced shifts unparalleled in our history. We have seen the majority of the world’s population lifted out of poverty and subsistence farming, and transformed into a highly educated, highly connected and historically wealthy society, driven by rapid technological innovation.

The world of 1800 would have been very recognizable to an inhabitant of the year 1600. But the year 2016 would be beyond unfathomable to an inhabitant of the year 1816.

And that transformative force is not slowing down. In the next 30 years, the 20th century conception of work- one that has dominated the modern age, may break down completely. But don’t take my word for it: here’s former US Secretary of Labor, Former Harvard and Brandeis Economics Professor, and current Professor of Economic Policy at UC Berkley, Robert Reich, to tell you how and why technology will eliminate many professions in the near future:

Economic inequality, for centuries on the decline, is rising again, even at a time in which technology allows humanity to solve so many as yet unsolved problems. As the world has become richer and more productive, it has not become more stable or more equal. Those starting their lives today expect less from the future than did their own parents, even as technology’s ability to enrich our lives has continued to grow exponentially.

And the role of the human in the economy may soon become the biggest of such unsolved problems.

Today, according to conservative estimates, half of all jobs are under threat from automation, or will be eliminated within the next 20 years. If the growth in computing power and complexity predicted by more optimistic thinkers, such as Ray Kurzweil, are correct, then these estimates are perhaps understated. A majority of traditionally employed positions may have disappeared by 2035, replaced by robots and artificial intelligences that are more efficient, reliable, safer, and more trustworthy than human employees ever could be.

Machine learning and big data mean that soon, even jobs considered relatively “safe” from automation will be under threat. Contract and tax attorneys, computer animators, programmers, even medical doctors, may soon find themselves in competition with algorithms that know more than they do, work faster and more accurately than they can, and fulfill the important functions of their jobs with inhuman efficiency.

In this world of automation and machine intelligence, there are only really two foreseeable futures: one in which people throughout society benefit from technological advances, and one in which the majority of us suffer from them.

There’s a good reason that the UBI, or Universal Basic Income, has been such a fêted topic among those who have benefited most from rapidly advancing new technologies. While Silicon Valley and other centers of tech innovation have become rich and bloated with cash, they have duly observed that the economies and societies around them have failed to be transformed in quite the same way.

While standards of living have risen steadily in cities around the world, rural regions have failed to keep pace, and have even slipped further behind economically than they were a half century ago. Every day, the tech industry works to eliminate jobs. From Uber to Apple, automation and machine learning are now the focus of most of the attention of the tech industry.

And that’s a problem. Because the tech industry, as it works tirelessly to automate and digitize much of the economic productivity of the world, has begun to sense a threat to the core of that growth. It has begun to grasp that there are fewer and fewer people who will be able to buy the products that it produces. A collapse in the consumer economy would mean an end to demand for all that innovation, and the high profits that these companies now enjoy.

Like the oil industry decades ago, with its early awareness of the dangers of global warming and tetraethyl lead contamination, the tech industry is keenly aware of the economic contagion it is now spreading. Rampant automation’s natural conclusion is the end of the modern economy; the end of innovation. That is, unless we do something about it.

First, a bit of history: the Universal Basic Income, (as well as its other flavors and cousins such as the “Social Dividend,” the “Prebate,” and the MBI or “Minimum Basic Income”), as a modern concept dates back to economists and intellectuals of Enlightenment Period, including political theorist and American revolutionary Thomas Payne.

The idea is in fact much older, dating at least to the Roman Republic, when inhabitants of the city received food stipends from government dispensaries, to keep people (the source of cheap labor) from fleeing to the countryside in search of a living wage.

And the concept has in fact already been in practice in developed countries for at least the past century, such as in the American Social Security System, and perhaps most famously in the earned-income tax credit, created in the 1970s, and based upon the work of conservative economic theorist Milton Friedman. Friedman wrote in 1962:

“The advantages of this arrangement are clear. It is directed specifically at the problem of poverty. It gives help in the form most useful to the individual, namely, cash. It is general and could be substituted for the host of special measures now in effect. It makes explicit the cost borne by society. It operates outside the market.”

Friedman’s support of the idea, formerly one favored by more progressive economic theorists, helped to cement the concept as one of interest to many philosophical viewpoints. Today, thinkers across the political spectrum favor some form of the UBI, viewing it in turn as a poverty relief measure, a way of decreasing government bureaucracy, and a means of redistributing wealth more evenly in the consumer economy.

Today, it is enjoying a renaissance, with governments from Finland to Switzerland considering it seriously, and nonprofits and private companies like tech accelerator Y-Combinator undertaking actual experiments with it in the field.

For a more complete history, read this fascinating piece by 538, an influential and popular blog that deals with topics related to data and statistics, including in economics, sports, and politics.

The details of Universal Basic Income and how it works vary according to the source, but principally all agree on the broad strokes.

First, advocates for the UBI call for the elimination of most of the modern welfare state. Unemployment, disability, retirement, child benefits, food stamps, and other government assistance programs would be replaced by one program. That program would give each citizen, regardless of financial situation, a single, equal stipend, which would represent the basic needs of an individual in that nation.

Many flavors and approaches to accomplishing this outcome have been proposed. In some versions, the UBI is meant to provide a subsistence level of income for an individual (as is the case in Finland’s much publicized proposal for a UBI experiment in 2017), and in others, it is enough for each citizen to “become an active participant in society,” such as in Switzerland’s recently rejected referendum proposal.

Each scheme currently proposed has its unique stated goals, from increasingly the willingness of individuals to retrain and to work part-time, or to pursue entrepreneurism, to minimizing bureaucracy, to encouraging volunteerism, family togetherness, and social cohesion in societies with aging populations. All seek eventually to end chronic and destabilizing economic uncertainty.

Despite their different approaches, most proposals seem to agree upon are the basic facts: administrative costs of social welfare programs are high, and produce poor incentives among the working and non-working population, keeping able members of society out of the workforce, and keeping unproductive works within it.

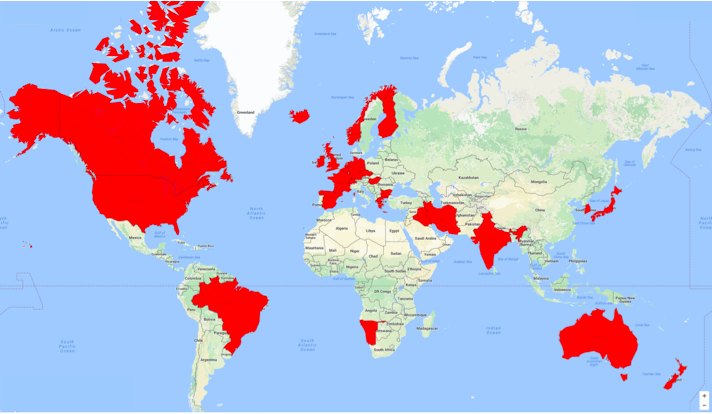

A map of countries around the world that are either experimenting with, or seriously debating the UBI

One of the key objections to the UBI is the fear, largely associated with cultural mores of capitalism and post-communist societies, that a guaranteed income would produce an idle population with no work ethic.

There is some validity to this fear, as advocates have pointed out.. Writers such as Tim Worstall have highlighted the fact that traditional social welfare systems have been shown to create so called “welfare traps,” wherein economically vulnerable members of the population are disincentivized to work, for fear of losing their welfare.

However, as Worstall notes, the UBI shouldn’t necessarily create these perverse incentives, because it is not tied to individual means tests. Experimental data has shown, in experiments conducted in Manitoba Canada and Namibia, from the 1970s and 2008-9 respectively, as well as in India starting in 2011, that Universal Basic Income did not produce an incentive not to work, except among members of the population that had out-of-work responsibilities, such as caring for children and family members. Nursing mothers were the most likely to stay out of the workforce for longer under the UBI.

Further, these experiments demonstrated that average household buying power increased, and that economic activity in the experimental regions also increased, with a higher average standard of living persisting afterward.

While data from some experiments has shown that a short-term supplement to income does discourage work, such as in one Canadian study, this effect is tied to the knowledge among subjects that the income is temporary. When the income becomes indefinite; disposition towards work does not appreciably decrease.

In fact, the government of Finland found this evidence so convincing, that its recent proposal emphasized that UBI could increase workplace participation as an average over the whole population, in part because it would end any existing incentives to remain outside the workforce, and would encourage people to seek part-time employment rather than wait for a full-time position to become available.

Clearly, there is not yet enough data to prove categorically that UBI will produce these effects everywhere. However, the evidence in favor so far is highly compelling.

“50 years from now, I think it will seem ridiculous that we used fear of not being able to eat as a way to motivate people.” – Sam Altman of Y-Combinator on the Basic Income.

The economic logic of the UBI system is based partly upon the concept of “aggregate demand,” popularized by the influential early 20th century economist Alfred Maynard Keynes. Essentially, Keynes showed that governments could influence economic growth by directly investing in economic activities -particularly infrastructure development- that private industry had less incentive to invest in.

Keynes’s theories have influenced developed nations for the better part of a century already, and have been responsible for the massive growth in government spending as a proportion of total GDP in essentially all developed countries. The New Deal, and the Marshal Plan are famous examples, though such programs are now pervasive around the world.

Keynes’s theories led to massive expansions in government spending, and to governments becoming the world’s leading employers. Today, the US Department of Defense alone is the world’s largest single employer, employing 1% of US citizens– a population larger than that of over 80 countries.

But more and more, his theories are being accepted in a broader context. Already, these theories have been extended to include direct cash injections into financial institutions, such as in the famous “quantitative easing” monetary policies of the late 2000s. These initiatives were all intrinsically linked with attempts to generate consumer demand and economic activity. Why, some now argue, doesn’t the government simply inject cash into the consumer economy directly?

What makes the UBI unique is that it attempts to achieve these same goals, without the need for expansion of government itself. If every citizen is receiving a stipend, wage competition has a hard lower limit. Employers must provide wages (and working conditions) attractive enough to employees to get them to work, even when working is not necessary to their basic survival.

At the same time, work that is not attractive enough to workers, and not economical enough to allow wages for that work to be increased, would face powerful pressure towards automation. Boring jobs would be very well paid, or they would not exist at all. Dangerous jobs would have to be made safer. Lower paying jobs would have to be more interesting or fulfilling.

In this scenario, demand for goods and services would rise, as many citizens would enjoy both more free time and a higher standard of living. Those with jobs would demand higher pay (as a proportion of corporate profits) and have more to spend. And those who would be put out of jobs because of automation would also have the time and energy to devote to other activities, from starting businesses, to pursuing hobbies, arts, and other non-economically focused activities.

Supporters of the UBI suggest that this process would produce a flowering of new culture and budding economic activity. More art, more music, more travel, more study, more hobbies and more hobbyists. It might produce what some hail as essentially a post-capitalist world, in which the freedom of individuals to choose how to dedicate their lives would create an explosion of innovations in everything from the sciences to entertainment.

And, some hope, these changes in the driving forces of society would produce a new politics as well- one in which class struggle, nationalism, and tribalism would be muted or dismissed entirely, in favor of humanism, environmental stewardship, scientific exploration, and the pursuit of peace and equality.

StartupYard Batch 7: Visualized

StartupYard Batch 7: VisualizedThis site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

OKWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

Privacy Policy