Last week, we were happy to invite 9 really promising startup teams to StartupYard’s March 2015 acceleration program. As with all rounds, there were loads of questions, and a few startups that weren’t quite sure what they wanted to do. StartupYard was, when it started, one of the only options in Central Europe for the kind of program that we have.

But today, with increasing competition from other accelerators in the region, as well as the muddying of the waters between what defines an “incubator,” vs. an accelerator, and the myriad different terms that startups can be offered, these decisions are becoming harder to make. As the level of progress for the startups we accept has risen, so has interest in those startups from other organizations. It’s a confusing time for startups, and we’re seeing the results today.

An Untypical Situation

One of the startups we accepted last week came back to us with a strange problem. Strange, from our perspective, because it actually *isn’t* a problem at all, but from their perspective it seemed a vital concern. The startup (who we will not name), informed us that they would be attending a competing accelerator in the region, but that they’d welcome us to call and have a chat about the decision. I called them immediately. While it’s obviously their decision, and their responsibility, to choose the best course, I was interested in their reasoning so that StartupYard could improve either in our communication about the value of our program, or in our program itself. What was another accelerator offering that was more attractive?

The founder was expecting my call. The other accelerator, was “going to give us a higher valuation,” he said, gravely.

I wasn’t sure what he meant. “Ok. I understand that any deal you have with another accelerator is confidential… but may I just ask what you mean by that? Are the terms they’re offering different from ours? Less equity for more capital?” “No,” came the answer. The terms, it appeared, were the same: 30,000 Euros for 10% of the company. “Well, in that case, I am just wondering how you think that your company’s valuation would be higher if the terms are the same.” “Well,” came the response, “they are offering a higher valuation based on the costs to the accelerator.”

To make a long story short, what happened, I think, is this: the other accelerator, in their communications with startups, or even in their terms, was implying that their costs (the amount of money they spend internally on operations and on benefits for startups, like food, events, offices, housing, travel, or anything else) would be figured into the total amount of money they were investing in the startups.

That’s a little bizarre, not least because it’s redundant: the costs and risk that an accelerator incurs are part of its justification for such a high percentage of a startup, at such a relatively low valuation: we take 10% of companies, and give only 30,000 Euros because it costs so much, and because it is so risky. There are not many other types of investors who would commit to that level of investment in anything after a very brief application, and a handful of meetings. Nor would many investors put money into the companies that we fund at the stage at which we fund them. Most investors wouldn’t have the time or expertise to make those kinds of judgements. That is why we exist, to fill that gap in the funding cycle, and improve the chances of standout startups to succeed in later rounds of funding. We don’t “give” startups a valuation. They arrive at a valuation with their investors as part of broader negotiations. The investors and the startups decide together how much the investor wants or can put into the company, and how much of the company that investment ought to represent.

It’s bizarre too because it is so transparent, and so arbitrary. If we were to include the costs of accelerating a startup as part of the “cash” investment that we give startups, we could theoretically state that our “investment” in the companies is around 60,000 Euros. That would give the company a theoretical pre-money valuation of 600,000 Euros. But that figure, and its basis, would be meaningless in determining the value of the company, either in pre or post-money rounds. We could go further even, and state that the value of our program (which includes over 250,000 Euros in perks packages from selected partners) is “worth” over 300,000 Euros. At 10%, that would give our fledgling companies a “valuation” of over 3 Million Euros. Now we’re talking!

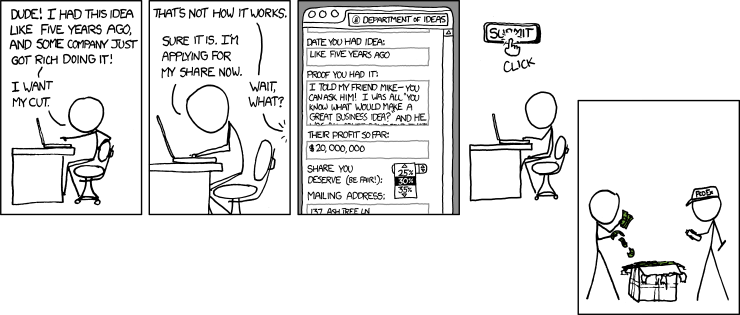

Funders and Founders does a decent job of breaking down the difference between a “pre-money” and “post-money” valuation. And why they are so different.

Double Or Nothing

But any investor smart enough to chew gum and walk at the same time would want to know one thing, and one thing only about these figures: how much of that is cash? What relationship does the amount of cash spent have to the number of users/clients/sales the company has, will have, or could have in the future? Traction. That’s it. That’s everything. And if anything, the idea that a company has a 600,000 Euro valuation, and still has the user numbers and traction of a 300,000 Euro company, is worse than the alternative. And to pile on, a startup that receives in-kind services and accelerator help, and actually represents that help as a form of asset to the company is lying and misrepresenting itself to any investor.

They are deceiving the investor as to the real market value of the company, because while an accelerator program absolutely should raise the profile of a startup, the results that an accelerator brings should be evident in the skills of the team, the company’s go-to-market strategy, and the actual gains in traction the company has made already. To include the dollar value of an accelerator program would be to ask for double the credit, for the same amount of work. It would be like charging an administrative fee for processing an administrative fee. Credible investors, the smart kinds of investors that startups should be courting for their first investments, will not view that kind of sophistry with kindness. They will punish a founder for it. And, having lied and misrepresented itself once, the startup and its founders will have poisoned the pond with that investor for any future deals.

The Valuation Trap

This is all what I’d like to call the “valuation trap.” The idea that investors are going to be impressed by the pretension of talks about a higher valuation without the fundamentals to support it, and that this will push investors to put more cash into a startup for less equity than they normally would. That is a lie, and a trap. While you may trick a naive investor, early on, to buy into your company for vastly less equity than the investment is worth, that will work exactly once. And all future investors, the more sophisticated ones that will look with concern at your actual cash resources, and their implications when it comes to your team, your traction, and your userbase, will see the scam for what it is. Valuations have to go up, not down. If they don’t go up, early investors aren’t rewarded for their faith in your company. And allies, people who are more likely to be supportive of your efforts (and have backed up that faith with real money), will be burned, and may turn on you.

If you bring a naive investor in at a low price, based on a dishonest representation of your company, then the next investor will be wise to the scheme, and will not invest at the multiple you are hoping for. Instead, they’ll insist that the valuation needs to either not go up at all, or to go up only slightly. This may be the only way that you can get investment at all in later stages. And what will you tell that first investor, the one who believed in you the most, when another investor comes in and gets even more equity out of your company, for the same price? If an angel investor comes in at 50,000 Euros for 2 percent, and the next investor comes in at 150,000 for 20 percent, you’ve just cheated that angel investor out of either a great deal of money, or a good chunk of equity in your company. That’s how he/she is going to see it, even if you had no choice. The numbers are supposed to go the other way, and suddenly the angel investor has paid 50,000 euros for something worth 15,000.

Given all that, the idea that you would even want an artificially high valuation for your young company is specious, at best. What about your company is more attractive to an angel investor at 600,000 Euros than at 300,000? If he/she looks at your burn rate, your traction, your product, and your team, and sees real value there, the lower the valuation, the more attractive your company becomes as an investment. You always have to give more equity to early investors. So keeping your valuation grounded is an important thing when considering an angel round. And an angel round or a seed fund is how most startups we work with are going to raise their first serious investment after the accelerator. Few have enough traction, enough history, or enough of a convincing business plan to attract a serious VC deal early enough to avoid having angel investors or doing a larger seed round.

An Accelerator Is Not A Typical Investor

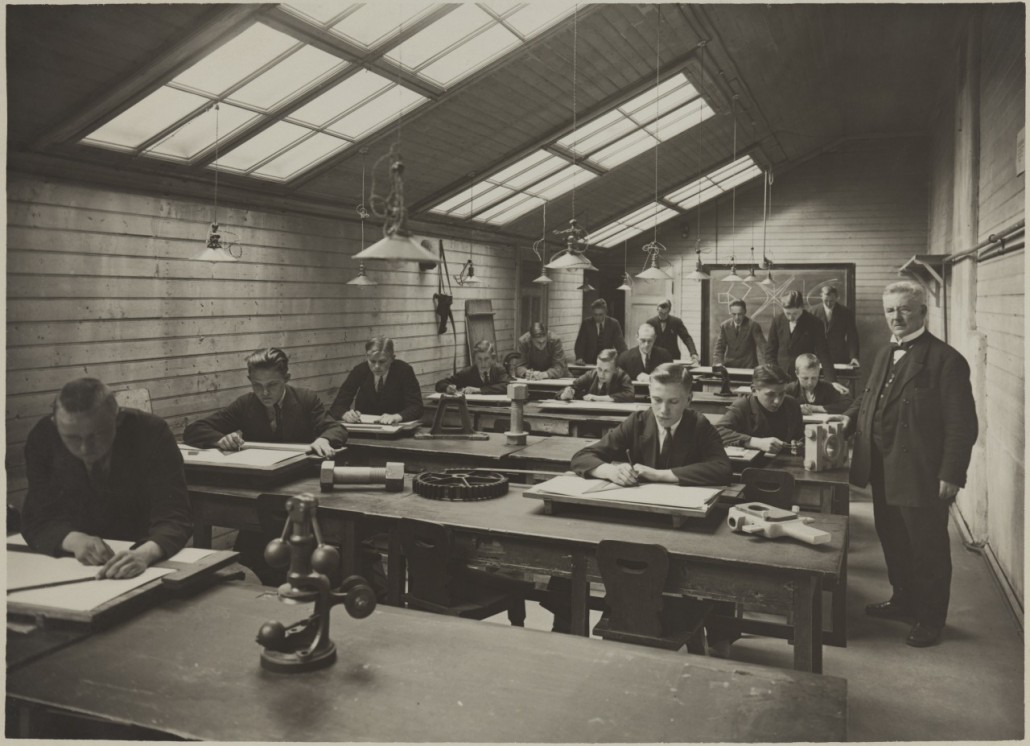

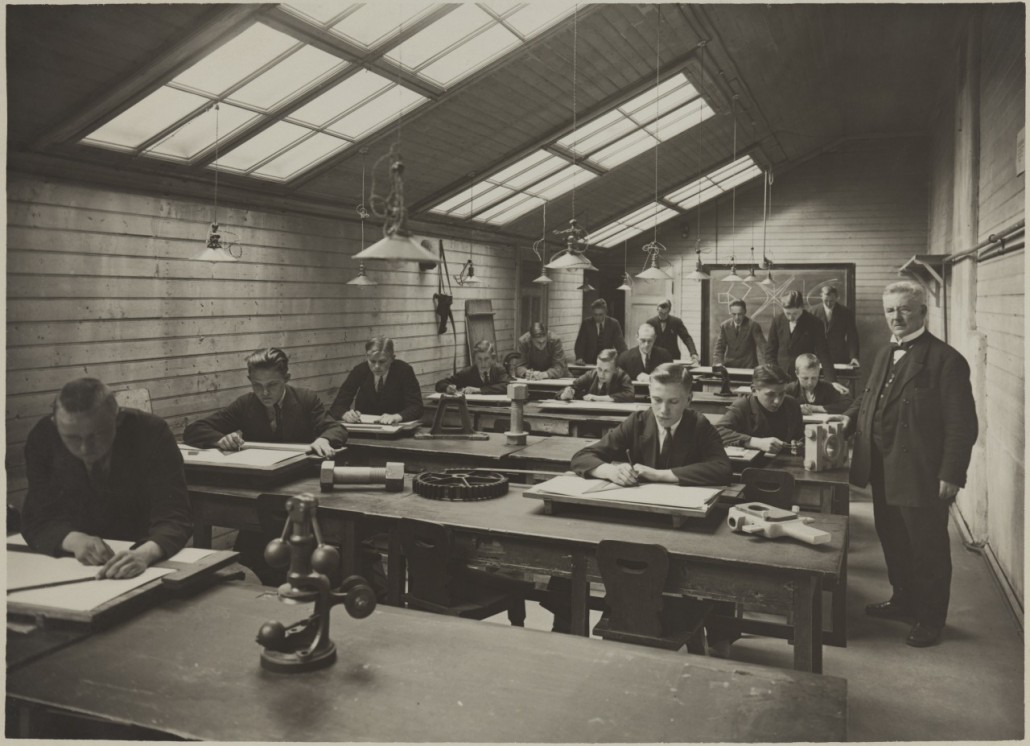

StartupYard at its founding in 2011. We’ve come a long way.

If you’re looking at an accelerator as a potential source of cash, and nothing more, then you’re looking for what will ultimately be a pretty bad deal. The equity split will not be favorable for the amount of money involved, and you’ll waste a considerable amount of your own time in the accelerator program- time you may see as wasted. We always have a few applicants who are obviously treating us like a potential source of cash, and a hassle they’ll have to deal with, rather than an opportunity. We’re not insulted by that. Some startups don’t need our help, and wouldn’t benefit much from joining us. Either they’re already accomplishing what they need to, or they aren’t, but they aren’t equipped with the humility necessary to use the help we would offer. Startups that don’t think they need our help, but are willing to take a 30,000 Euro investment for a 10% equity stake, probably do need our help. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t need the money either. But needing help and accepting help are two different things. And we’ve become more practiced at spotting the difference.

An accelerator is not a typical investor. And the equity it takes doesn’t define the value of the company it invests in. Investors should know this. If they don’t know it, you should tell them. A good accelerator should deliver enormous value to a company it invests its time, knowledge, and money in. But at the same time, a company coming out of an accelerator has to justify its valuation based on its own merits, which I’ve enumerated above. An accelerator can’t and shouldn’t “give” any valuation. A valuation is a number you arrive at as part of a negotiation with your investors, and should represent both the interests of the investor, and the interest of your company. Your interests as a company are 1) to get enough money to operate and grow, 2) to leave room for future investment rounds for the same reason, and 3) to become ultimately profitable. A sky-high valuation can work against some of those goals early on, making it harder for you to get investment, and leaving no room for your valuation to grow and attract new investors, while rewarding the early ones. A higher valuation will also set expectations for future profitability that may never materialize, hurting your chances of selling the company, and of appearing successful in comparison to the competition.

An accelerator like StartupYard works to make sure that your product, your team, and your plan are solid, and worthy of investments. Then we work to connect you with investors, and get you ready to work with them. It is in our interest that you not only get investors, but that you get the right investors for your company, at the right valuation. Some accelerators take less equity than StartupYard, but the amount of equity taken is not a function of how greedy an accelerator is. I can assure you that StartupYard, while it gives less cash to startups and takes more equity, is not seeing the upside that Techstars and Y-Combinator are. And the moment StartupYard can afford to, we will offer more cash for less equity than we currently do. We would have to, but it would also be in our best interest. That’s why we tripled our cash/equity ratio just this year, and are seeing even better prospective startups for the program as a result.

But even as we tripled our funding for startups, and made significant investments in our team, our program, and our facilities, we didn’t triple the red tape necessary to be accepted to StartupYard. We are offering, with each successive accelerator round, a more attractive package for our investors, and for our startups. It’s a process, and we’re not at the end of it. Just as we can’t and won’t sell our investors on value we don’t yet have, we would never advise a startup to do so either.