Exponential Innovation: Past and Present

(Part 1)

(Part 1)

“Software substitution, whether it’s for drivers or waiters or nurses…it’s progressing…. Technology over time will reduce demand for jobs, particularly at the lower end of skill sets… Twenty years from now, labor demand for lots of skill sets will be substantially lower. I don’t think people have that in their mental model.”

This post is a part of our series on Exponential Innovation. In this series, we explore the roots and consequences of rapid technological and social change, specifically related to the tech industry, but also as it effects all aspects of modern life and the modern world.

This post will take a tour through the history of employment, from the early 20th century, to today, and talk about how technology’s relationship with employment has changed during that time- and will change still more in the years ahead. What will your job be in 2026, and what relationship does that have to the history of automation, and the concept of employment?

This is a two-part post. Part two will be released later this week. You can read other entries at the bottom of the page.

Two years ago, Inc.com labled the above missive from Bill Gates on the future of employment as “chilling.” But in this series, we’ve tasked ourselves with asking a simple question: “is it really?”

There’s no doubt that automation has eliminated millions of jobs from the modern economy in the past century, and that in recent years, that trend has not slowed. Today, the “gig economy,” is rising as a replacement for the staid and steady paradigm of the 20th century, in which a typical white collar worker spent his or her career receiving a paycheck (and a nice pension) from one or two organizations.

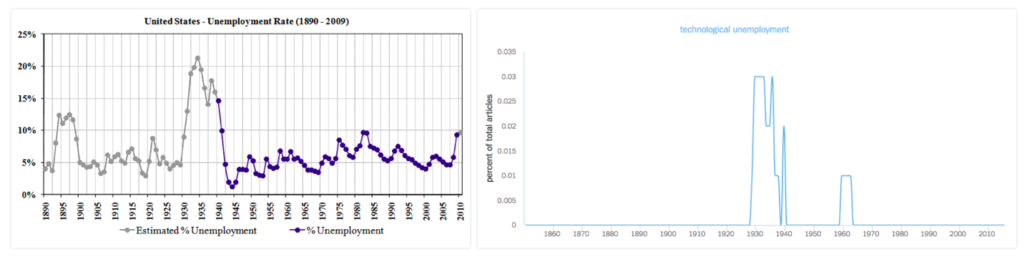

But on the other hand, people, including the media, have been blaming technology for unemployment for at least 125 years. Here’s a handy graphic to prove that:

(source: Louis Anslow’s fascinating Medium post. Link above)

(source: Louis Anslow)

The data shows that the media is much more likely to write about technological unemployment when unemployment is rising. But unemployment, according to US government statistics, rises and falls in a predictable pattern: it spikes, and then it slowly falls until another spike.

This suggests that the real proximate cause of unemployment is not automation, but rather a sudden shift in the financial markets: booms ramp up, but busts are sudden. Every major financial upheaval of the last 20th century had accompanying job loss- and each time, existing industries did not fully replace their pre-crisis work forces.

As busts happen, there are corresponding rapid shifts towards automation, as industries look for ways of saving costs while maintaining outputs to stay competitive. That is a feature of market capitalism, as much as it is a bug. Necessity is the mother of invention. History tells us that rapid automation usually follows a financial upheaval, but doesn’t necessarily cause such upheavals.

For this we can find many examples, such as the hollowing out of the US auto industry from the 1980s on, which followed on the OPEC crisis of the late 70s, and pushed consumers toward lighter, more gas efficient cars manufactured in Asia.

It’s no coincidence that Japanese car manufacturers were relying on automation to undermine American competitors in the 1980s. Job losses were real, but they were a symptom of an inefficient industry, that wasn’t moving fast enough to keep up with modern demands. New technologies destroyed these jobs and consequently the economies surrounding those jobs, but the net result was a sharp rise in the quality of cars, and eventually, a rise in the standard of living, even in the areas affected by the bust in the car industry.

So technology did create unemployment. More on that in a bit… but first, it’s important to keep in mind that:

It’s easy to discount the fact that modern conceptions of employment are not a sacrosanct part of human history, but a recent phenomenon. The concept of a worker, of a person’s worth to society being judged according to an hourly or monthly wage, is linked with the rise of automation from the 18th century onwards.

Until about the 14th century, western societies were divided into a set of essential castes: landowner aristocracy, clergy, serfs, and a small subset of artisans, who fulfilled skilled trades such as blacksmithing, weaving, masonry, and other marketable skills. Because about 70% of the population was needed to produce food, economic mobility was extremely low, and over the course of a thousand years, serfdom had become so institutionalized as to become a part of the fabric of society- landowners came essentially to own those who worked the land, locking up the majority of the population in an inefficient agrarian system that did nothing to incentivize innovation.

But beginning in the 14th century, catalyzed by the Black Death, in which as much as 40% of the European population, and 30% of the world population died in the space of just a few years, the economic order rapidly began to change. As the European population was decimated, two things happened: first, food and available land became abundant, and second, available labor to work that land became scarce. What followed was a period of rapid economic and social reorganization, in which many who would normally have spent their lives working on farms, began to enter trades that were needed to meet the demands for automation.

At the same time, workers gained new and unprecedented access to literature, entertainment, and new goods that were being produced by the swelling population of artisans who were no longer tied to the land. The consumer class had begun to take shape, and it began a cycle of economic growth that drove yet more innovation, more wealth distribution, and more technological and social change.

As individuals gained more control over their economic lives, and began to be able to demand fair compensation for their work from the abundant food now available, median wealth skyrocketed, and the power of the landed aristocracy began to crumble. Over the course of 3 centuries, the aristocracy was challenged at every level, eventually culminating in a series of revolutions, and the birth of the modern nation state. The state, now organized around the political objectives of common people, became a servant political class, and later, a professional class, as aristocracy largely died out across Europe.

As economies around the world gained access to exponentially more efficient modes of energy production (steam, then coal, then oil, etc), there was a simultaneous and sustained boom in the invention of devices which took advantage of these new power sources. The power loom moved textile manufacturing away from the piecework system of the agrarian age, and into the factory. The tractor and combine harvester then moved agriculture from the small farm to the factory farm.

From the 18th to the 20th centuries, there was no aspect of the world’s economic life that was not profoundly changed by automation. And for the vast majority of the world’s inhabitants, this meant better access to an ever higher quality and range of goods. The social changes were not always smooth, nor were the new economic systems always humane, but nevertheless, on average, the world’s wealth exploded during those two centuries, in a way never before dreamed of.

And somewhere along the way, the locus of most human lives became “the job.” As automation became an essential characteristic of growth, the need to tie the value of labor directly to the value of its output became ever more pressing. We don’t have to stray that far from the story of the American car industry to see an example of automation shaping the modern concept of employment.

In 1913, Henry Ford, the father of assembly line production and massive automation, faced a massive shortfall in available labor for his car plants. A typical assembly worker stayed in his position only a year or two, and new workers were expensive to find and train. The problem wasn’t so much that workers had many other options, but that even at $2.34 per 10 hour day (at the time, a very competitive wage), the work in Ford’s plants was seen as boring and repetitive. So much so that workers would quit to take lower paying jobs that were less monotonous.

Ford, characteristically, took the long view of this problem. He shocked the world in 1914, by announcing that he would slash the workday to just 8 hours -an unheard of luxury- and simultaneously more than double the wages of most of his workers to $5. At the time, analysts predicted that Ford would bankrupt himself in the process, costing his business over $10 million a year, and zeroing his company’s profits.

But as we now know, this did not come to pass. Instead, Ford attracted a new cohort of workers who remained loyal to him throughout their working lives. Instead of an average employment period of less than two years, Ford’s average employee stayed with the company for 10 years or more. Many worked their entire lives in his factories, increasing their efficiency by building a vast store of working knowledge about the machinery, and about each individual task, and contributing from the bottom up to make the manufacturing process ever more efficient.

Another thing happened too: Ford’s workers, with more leisure time and more pay available, along with a heavy dose of loyalty to their company, bought Ford’s cars en masse. As other industries responded to Ford’s model by raising wages and shortening days, a new class of working people with money to spend transformed America into the world’s mecca for the personal automobile- along with a host of other luxuries the rest of the world’s working classes could scarcely imagine for themselves.

Ford’s innovation not only affected the lives of working people in America. It served as inspiration for an entirely new view of how an economy could function, and subsequently how the government could influence the economy in times of need. The economist John Maynard Keynes, for example, expanded on the results of Ford’s experiment (among much else) to develop the basis of what became known Keynsian Economics.

Previous economic theories relied on the idea of an “economic equilibrium,” in which the demand for goods and services would always be greater than the economy’s ability to produce them. This meant that all the goods that the economy produced must eventually find buyers, and that any goods that were not bought, were thus overpriced. The economy could react by either lowering the cost of producing the items (by driving down wages or increasing efficiency), or stopping production of excess goods.

Ford’s experience was in contradiction of that model. Instead of lowering his prices, or lowering his costs of manufacturing goods, he instead raised his costs, and increased his prices over time. The subsequent increase in demand for his cars meant that his profit per car was lower, but that he sold many, many more cars overall.

Keynsian Economics recognized this phenomenon and theorized, essentially, that economic output was closely connected with what Keynes termed “aggregate demand.” This meant that the growth of the economy was not necessarily driven only by the cost of production, but also by the diversity of consumer needs, and rising consumer demand for higher quality. Thus, Keynes theorized, the economy would grow faster if more consumers had more money, forcing producers to make a wider selection of goods, at a broader range of prices.

Government then, according to Keynes, could stimulate economic growth by increasing the demand for workers through government funded projects. The wage competition generated by these new jobs would push wages higher, and force manufacturers to seek new efficiencies, which would lower the cost and raise the quality of goods, while also distributing a larger share of the economic output in the form of wages.

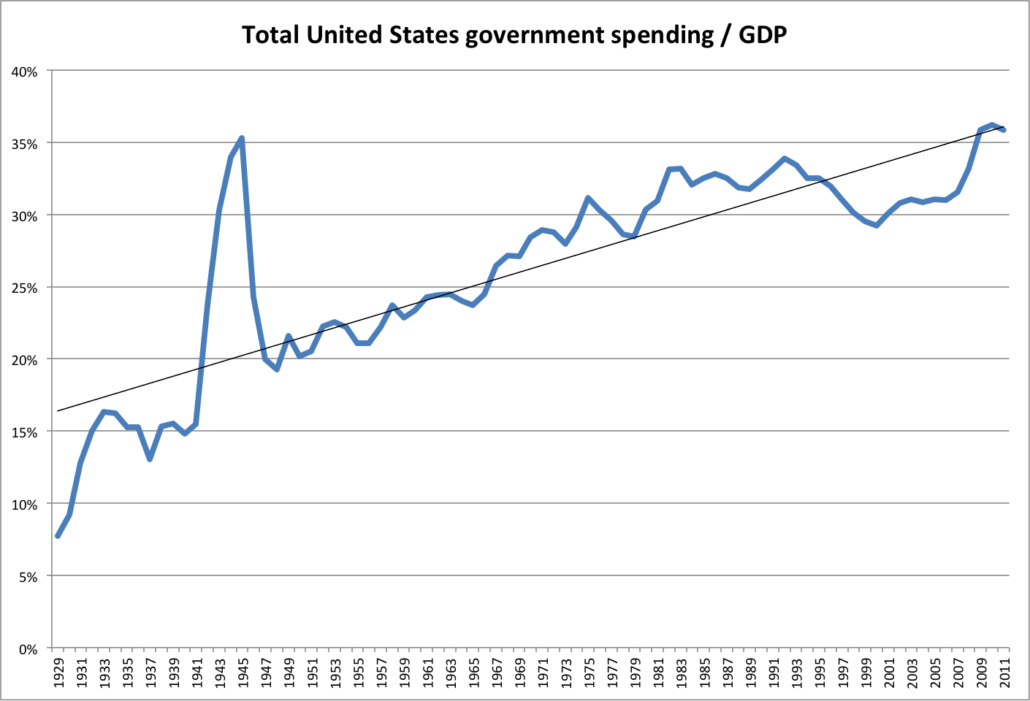

Keynes’ theories became highly influential following the economic collapse of 1929, and would go on to shape Europe and the United States’ approaches to fiscal and government policy for much of the 20th century. Heavy government investment into public infrastructure from the New Deal of the 1930s in America, and the Marshal Plan, from the late 1940s in Europe, institutionalized the approach of governments stimulating economic growth by raising wage competition, and driving consumer demand upward.

Governments in the 20th century went from small operations with limited influence on the economy, to leading employers, nationalizing many services that had previously been either locally administered, private, or non-existent, like the postal system, health care, education, public works, and banking. From the beginning of the 20th century to its end, governments transformed themselves from administrative centers into the economy’s largest single employers and economic actors. Government share of GDP rose throughout the world, often from less than 5%, to more than half of total GDP. Below is a chart of the growth in the share of GDP from government spending in the United States during that period.

All the while, the economies of the western world relied more and more heavily on employment as a model for economic growth. Wage earning, once confined to the manufacturing industry, became the norm for the vast majority of the population, while piece work, self-employment, and trade work declined.

Coming back now to the end of the 20th century, much of that institutionalization of employment was beginning to fray noticeably. Technology’s progress forward meant that more and more, goods manufacturers were able to distribute production to areas of the world where wage demands were lower. This meant that they could reap higher profits, but at the same time, it also put downward pressure on wages in developed economies.

Two things resulted. First, more and more people sought higher education in developed economies in order to be competitive for higher paying service jobs, and second, new industries arose to employ this base of higher skilled workers. It’s no coincidence again that the rise of the computer industry and a demand for skilled engineers and programmers occurred at exactly the point that union labor in manufacturing began to decline. Higher skilled workers made higher skilled jobs easier to fill, and consequently drove up consumer demand for better and better tech products, along with many professional services.

Of course, as a side-effect of this transition to a service/consumer economy, western countries also transitioned to a more debt-based economic model. Now, for the first time, education and housing became pools of debt that would enrich a relative few. This problem has festered for decades, and has yet to be resolved.

At at the same time, new technology and the demand for new services also helped reinvent the service industry, moving many union and low-skilled workers away from manufacturing and labor jobs, to service jobs that employed new technology. The help desk operator, the financial analyst, and the IT specialist replaced assembly line workers in developed economies, staving off rises in unemployment due to the dislocation of manufacturing jobs. Government also began to step in, first with welfare programs like social security, and later with unemployment benefits and different forms of tax redistribution, like earned income tax credits.

Also at the same time, and at an accelerating pace since the late 1990s, the resources necessary to start a global business, thanks both to the globalization of many industries, and the disintermediating effects of new technologies like the internet, meant that increasingly small companies had access to new, unformed global markets in need of software and service solutions that had never been technically feasible before.

The startup then, that creature of the 21st century, was a child of globalization, and a reaction by many young people to the realization that the old system of employment enjoyed by their parents was breaking down.

In part 2 of this post, we will discuss the effects of “financialization” and the rise of the tech industry on modern concepts of employment and government.

Other posts in this series:

Ondrej Krajicek of Y Soft Ventures: Celebrate Results

Ondrej Krajicek of Y Soft Ventures: Celebrate ResultsThis site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

OKWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

The following cookies are also needed - You can choose if you want to allow them:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

Privacy Policy