What “Mentor Driven” Means To Us

What an Accelerator is For

A journalist visiting TechSquare this week asked me an intriguing question. I say “intriguing,” because as it was coming from an outsider to this business, it demanded a single answer to a question that is not often taken by itself: “what is a tech accelerator really for?” That kind of question demands an answer that applies to all parties: to the investors, to the startups, and to the general public. What do we do that adds value to the world in which we live? The answer I arrived at was this one, and I think it covers all of that: “a startup accelerator helps to manage, facilitate, and encourage intelligent risk taking.”

As Techstars has explained about their own roots, the current mold of accelerators was formed in reaction to risk aversion. Angel investors and VCs were, from about 2002 onward, inflicting far too much pain on startups to prove their worth before securing seed investments, which probably led more than a few worthy startups to stall out for lack of access to funds. The tech crash in the early 2000s had soured many investors on the market, and introduced big barriers to entry. Imagine a world in which Facebook didn’t have the money to get to its millionth user that first summer. This was a real danger at the time. But today, a service that has added half a million users in a period of several months would be unlikely to have that particular fear. The accelerator movement has been an important part of that shift away from risk aversion, to more intelligent risk taking.

What “Mentor Driven” Means

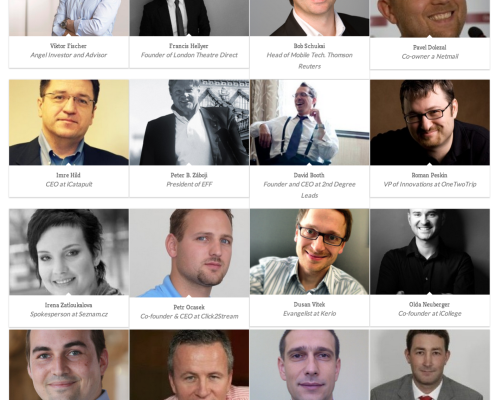

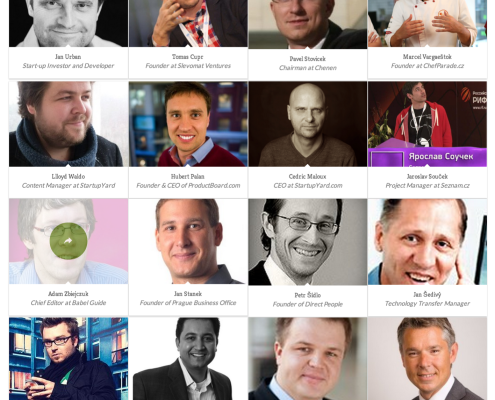

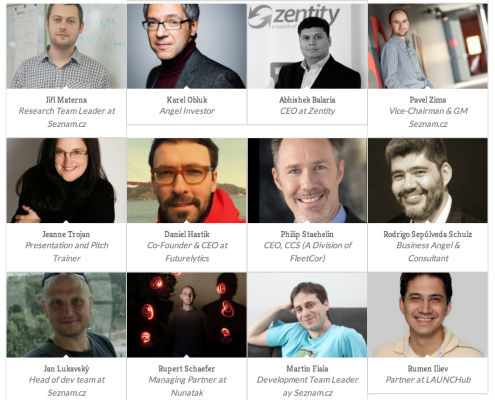

Over the past month, our teams have met with nearly 40 mentors each. That’s 40 meetings with entrepreneurs, professionals from within their areas, and CEOs of companies that have been in the position that our founders are in now. There have been so many meetings, that many of the teams have had moments of frustration with the process. One of the CEOs told me last week: “They all ask me similar questions, and I haven’t had time to do the things they’re all telling me I should be doing.”

Yes, it can be frustrating, but we also view that feeling as somewhat positive. A founder of a young company who is very aware of the potential problems he is facing is more likely to take a realistic approach to solving those problems, instead of avoiding them. He may be tired of hearing the same concerns, but he will definitely find ways of addressing them- if only so that he doesn’t have to keep hearing about them. He knows where he stands, and where he needs to be when this process is done.

Bad habits and false assumptions, when untested too long, can ossify very quickly, and poison sound decision-making. The accelerator is the antidote to that problem, forcing founders to address their toughest challenges first, rather than wasting time and money working in a market they don’t understand well enough. Constant early contact with mentors breaks up patterns of thinking and working that will lead founders wrong.

It’s About Who the Mentors Are

“Mentor driven,” means that the first steps a startup takes are in consultation with people who want them to succeed. Most of our mentors are not investors, and most will probably not end up working directly with any of our founders later on, but they are people who care about spreading knowledge, knowing their industry well, and making valuable and useful connections with each other, and with new startup founders. While basically all accelerators are concerned with helping their teams raise money at some point, at demo day, or later on, the focus at StartupYard is on giving the company the strongest possible foundation as a means to that end, and to making the company a success in general. Knowing and understanding your own industry, how people talk and behave, and how they think, are really vital elements of that kind of success.

Startups are Not in Business to Raise Money

A lot of startups quickly start thinking that they are in the business of raising money. That’s a cycle that’s easy to fall into. The second an investor wants to talk money, a founder has to completely change how he or she is thinking about the business, and fit that thinking to the way the investor thinks. If founders have conversations with investors too early in their own development, both as business people and stewards of their own companies, they can easily be taken in by the investor’s agenda, which is different, on a basic level, from their own.

A founder should be interested in his or her users, in solving problems for the people that will use their products, and in forming a company that adds value to the world in which they live. A good product or service company needs these goals above and beyond profitability in order to shape its future and give it purpose.

But an investor is only interested in realizing gains on their investments. If 1 dollar today can gain 20 tomorrow, they will invest. And likewise, if making a company stop and completely reconfigure its own priorities in order to win investment can turn 1 million dollars today into 20 million dollars next year, investors will encourage that to happen. So having a company planted on ground solid enough not to be shaken by incoming investment is very important. A founder has to have a vision of his company in 5 years. An investor doesn’t buy that vision, just the part of it that has an upside potential. We need investors to make many startups work, but that doesn’t mean investors should run startups, or tell them what they want too early in their development.

Mentoring can be a cure for that illusion. Talking to people who have taken on investments and regretted it, as well as those who have done it well and made it work, is an experience of great value to someone who has never had a conversation about money that involved more than 3 zeros.

But most importantly, mentors remind founders that their businesses have to work, not just as investment vehicles, but as *real* businesses. As I said: an accelerator is about taking intelligent risks. Putting 3, or 6 or 12 months of your time into a company is in itself a risk. So why not make it an intelligent one?

[ssba]