Anand Giridharadas: Winners Take All : The Most Important Book on Tech in 10 Years

/in Personal/by StartupYardWe don’t post book reviews often on this blog. Sometimes we recommend books we think our startups should read. We have a reading list, which deserves an update as well. More often we talk about books with our startups in person, and many that the management team recommend are standard fare for startups and business. Dale Carnegie, Al Ries, and business classics like Zero to One, Crossing the Chasm, or books and articles by Malcolm Gladwell.

This post is a bit different, because the critical consensus on Anand Giridharadas’s new book Winners Take All : The Elite Charade of Changing the World, has not yet been formed. Still Giridharadas’s well known views, first as a columnist for the New York Times, and then as a member of the speaker circuit he himself criticizes in his new book, are rare harsh words from a tech industry insider who knows of what he speaks better than most.

In truth, the book is a kind of validation for us as well. StartupYard has been publicly critical of “Thought Leadership,” and the incestuousness of the idea space that tech startups and corporations tend to occupy. We have been publicly in favor of many of the solutions that Giridharadas suggests, including Universal Basic Income. Still, his book comes as something of a wake up call for our industry. One that should not surprise anyone, but probably will.

“Making The World a Better Place”

When we refocused StartupYard 5 years ago on global projects with an emphasis on novel technologies, part of our thesis was that it would not be enough for us to “make the world a better place.” This is not least because “making the world a better place,” often functions as an excuse for failing to take on important, and yet smaller issues. Instead, we focused on developing the ecosystems in which we live and work, be they the city of Prague (in multiple cooperative hackathons with the city, and by investing in local startups), the Czech Republic, CEE, or finally, the globe. We also live on the globe.

We also tried to focus on problems with a deep impact on the world that could be widely felt. That led to our investments in companies like Gjirafa, Neuron Soundware, OptioAI, Rossum, or TurtleRover. Each of these companies does more than simply allow large companies to increase profit margins. They create new markets and new ways of looking at old problems. They create opportunities for small actors who can’t afford to compete with the bigger players. They drive competition, not individual competitiveness.

What we tried hard not to do was to choose startups and make investments solely based on the idea that these companies might be financially successful. Moreover, would their impact on real people’s lives be meaningful, measurable, and tangible, ultimately, to the founders and to us?

That might sound like “Making the World a Better Place,” but it’s not the same thing. To develop and push the world towards a more just, more fair, and more prosperous future is not to simply “make the world a better place.” In fact, it should not surprise the reader that new technologies can make the world a harder place to live in. These are issues that we must face as moral actors in the world. Thus: will the automation, or new ways of working and living our startups are trying to invent, make the lives of the individuals it is most important to, better in a meaningful way to them?

When we talk about a better world, we often just mean a better world for us. One in which we feel better about ourselves. Yet, this is not enough to help a person sleep at night. At least not to help this investor sleep at night.

Giridharadas gives shape to these thoughts in his book. He asks us: who suffers so that we may succeed? These are the people to whom a debt is truly owed, no matter who they are. Our responsibility to the world around us does not end with the interests of our shareholders. It extends to all who our technologies touch, directly or indirectly. It extends to promoting a moral worldview to the founders we work with – one in which greed is not good. Giridharadas also asks something more: what happens when success does come? What will we do when and if we do win?

Facing Win-Lose Scenarios

One of the themes of Winners Take All, is pointing out and challenging the insidious idea that any technology company can do essentially anything it wants to do, and still one can find “win-win” scenarios, in which the impact of their choices can be seen as positive for everyone involved. It’s ok that Uber destroys the taxi industry, because the net impact will be good. It’s ok that Airbnb might raise property prices, because in the long run, it will all balance out. Having personally met with and heard talks from executives at these companies, along with many other major tech players, I can assure you that they do not have a concrete view of how this balancing act will work

In tech, most do not take responsibility for this balancing out. We disrupt, but we don’t fix the problems we create.

Worst of all, investors and startups may justify their negative impacts on the world around them by spending the money they earn on fixing the very problems they created, via charities, or via yet new startup businesses. This can be like treating a hangover with more alcohol. It tends to lead to similar results. New approaches are needed.

Thus tech companies can disrupt and invalidate systems that employ and support large numbers of people, and they can justify this disruption by pointing to a possible future in which their impact will be seen as positive by those who suffer today. Often the worldview is passed down from the investor, to the startup, to the individual team member: “it doesn’t matter if we wreck a few lives… eventually they’ll thank us for it.”

This is not good enough. That is why StartupYard is in favor of Universal Basic Income research, among other governmental and regulatory approaches to protecting individuals, classes of people, and regions from the negative effects of the very innovation we invest in. We simply will not profit from a world that we are destroying. That’s also why we have consistently criticized governmental approaches to innovation that idealize the tech industry as a cure-all for social and economic inequality. We can do many things, but we cannot replace democratic institutions, or be the voice of unheard people.

Sometimes winners win, and losers lose. In a just world, and in a world we do want to live in, the losers don’t have far to fall. Losing is, after all, what almost all of us have to do at some point before winning. The waste and the pity of a winner take all world is that so many great things come from those who have lost something before – people who fail know the value of succeeding.

Survivorship Bias – The Nose Goes

Finally Giridharadas asks important and difficult questions about what it means to actually be a winner. Can we ever know, if we do succeed, that this success is due more to our abilities and our hard work, than to luck, or to the simple fact of who we are?

He reminds us of something that is also part of StartupYard’s DNA: the belief that someone’s CV is not their life. In our business, it is easy and in some ways much simpler to follow the signals of success that follow certain people through their lives. Did the person go to Harvard? Did they have a good position in a previous company? Did their past startup succeed?

We focus very little on these details, because they don’t tell us that much about people. There are plenty of idiots in C-level positions. There are plenty of bad founders from Yale or Oxford. Hard experience has shown us that a person’s CV doesn’t always have a strong relationship with their individual potential when it comes to founding and building a company. If we were to only look at Ivy Leaguers from prestigious tech companies as founders, we’d miss people who have no such credentials, but have far more important qualifications than that. Qualifications like knowing their customers better than anyone else. Like being more devoted to what they do than anyone else in the world.

What is interesting about the culture of startups is that we “celebrate failures,” but actually we celebrate learning from mistakes. True failures, like not working hard enough, not getting good enough marks in school, or failing to even act on an idea you had in the past, are not celebrated this way, because we don’t tend to learn from them. A story of real failure is not interesting, because it doesn’t have a happy ending. It just ends. Somebody who failed at 25 is inspiring. Somebody still failing at 50 is pathetic. We celebrate people who almost succeed, and probably will succeed in the future. That isn’t the same as failing.

The heuristics you use for making decisions about people should be based on your own experiences, and not those of others. This is what we call “instinct,” which for some reason has become taboo in the technology world, where everything is data and metrics driven. We believe in following your nose. Your nose tells you things your eyes and ears will never quantify.

Read the Book

Enough of my opinion on the topic. Read the book! I promise you’ll at least learn something you probably didn’t know before.

Guest Post by Ondrej Krajicek: What It Means to Be a Mentor

/in Interviews, Life at an Accelerator/by StartupYardAbout Ondrej Krajicek

Ondrej Krajicek is Chief Technology Strategist for Y-Soft, and Y-Soft Ventures, a Brno-based printing and 3d manufacturing tech company where he has been a team member since almost the beginning. Ondrej is a dedicated startup mentor, and a longtime member of our community, where he has published his thoughts and unique perspectives on the technology business and other topics many times. Today Y-Soft is one of Czechia’s few technology “unicorns,” and serves large and small companies all over the world. At Y-Soft, Ondrej considers it his mission to grow the Czech economy by encouraging technologists to focus on crafting superior products and relying on their best skills, rather than focusing on cheap labor and manufacturing.

What It Means to Be a Mentor

Thank you StartupYard for giving me the opportunity and looking forward to the next cohort.

I should have started writing this article after my mentoring day at StartupYard, which is November 21st. Having past experience with several cohorts, I just could not resist and started as soon as I got the idea. So it is rather sunny day in Texas and I am looking forward to working with StartupYard and the incubated startups once more. I am writing this to give myself more clarity on why am I doing this, what should I deliver to the startups I am going to talk to and what should be my take aways from the day. I also have a tiny ambition that this may change somebody’s perspective on mentoring and improve the experience for any mentors out there and those being mentored as well.

I have been working with StartupYard since 2014 and it has been a tremendous experience. They truly have a great team with three people who really stand out: Helena who handles all the scheduling, Lloyd who does a great job with no-nonsense PR (a true rarity in Europe) and Cedric, who leads it all.

You are not the smartest guy around…

I will never forget two immortal quotes from Bohumil Hrabal in Slavnosti sněženek: “Máte štěstí, že jedu kolem.” and “Říkají o mně, že jsem odborník.” Apologies for Czech, it really never gets old.

10 years ago, having been invited to be a mentor, I would probably feel honored and entitled. If repetition is the highest form of flattery, than asking someone to be your mentor is definitely the second highest. And after the thrill of being asked to mentor dissipates, the first thing I need to consider is my responsibility to the teams I am going to work with.

Being a startup team in a world class accelerator is an overwhelming experience. There is little time for everything and spending time with a mentor is an important investment on the team’s side. They are investing time, energy and money in that discussion, regardless of its length. And as a mentor I should never forget that.

I am not a mentor because I am the smartest guy around. I am not a mentor because I am successful. I am a mentor because I had to solve problems, perhaps similar problems in different contexts and I, my team and company survived to see another day.

So how can I make sure that the discussion is worth their while?

Be Useful

One of the best mentors I had the chance to meet, Ken Singer taught me one of the key principles of Silicon Valley: Pay it Forward. If someone seeks your help, help them — without expecting anything in return from them. Someone else, some other time, will help you too. Next time you are pondering how to replicate Silicon Valley success in the Czech Republic, think about this and the culture which is preventing this simple approach to take of here.

How does this apply to being a mentor? Do not expect any tangible benefit in return. You will not get shares or money just because you graced someone with your presence and shared your experience. Certainly not by answering few questions.

Being useful means adopting the mind set of freely sharing anything and everything which feels relevant to the situation. Connecting people with people.

Tell Stories

The real problem is that sharing is difficult. Robert Kaplan gave a great talk about mentoring which is available on YouTube.

If there is one principle I need to follow, one thing to take from Robert Kaplan, than it is that I should not tell them what to do. Kaplan claims that mentoring advice is only as good as the story, but what if it’s you telling them stories. Stories are about context, problem, solution and lesson — just like bedtime stories of our childhood. Just this time, it’s about business.

Instead of asking them to tell me their story and risking, that my advice would only be as good as their story, I should tell them mine and let them take what they feel they should.

I see mentoring as a form of leadership. This is the less obvious kind where I do not manage anyone, certainly not the team I am talking to. My biggest power over the team is listening.

That is easier said than done.

Ask the right questions

I usually start with three questions:

- How can I help you today?

- What can I help you with?

- Can I have a whiteboard please?

But no, these are not the right questions. As Kaplan teaches, leadership is about finding the right questions and my “right” questions are about users, employees and customers.

- Why is anyone going to pay you for your services or products?

- Why should people work for you?

- Why should your customers choose you and not your competitors?

The hard part is not asking these questions, but feeling the answers.

Own It

In 2015, Harvard Business Review published a nice article about how it is impossible to put yourself in the proverbial shoes of your customers. Cutting to the conclusion, I am not trying to put myself in the shoes of their customers.

I need to become one. This is where my stories help. May be, sometime in my past, I was in a situation which would require products or services of the team I am talking to today. My experience, if it is relevant, kicks in when we start debating the need, the constraints involved and how is their solution solving the problem. Which is now — for the time being — also my problem.

Mentoring is like acting. I love theatre: drama, comedy, opera, but I would be terrible actor. But here I can immerse, I just need to be authentic.

Share beliefs

Authentic means that I need to tell them the truth. Not that I expect to lie or think that some mentors lie, but if I am not authentic, they cannot trust me and probably won’t. This is not a place and time for rhetorical alchemy as I am not here to influence: no careful dosing of ethos, logos and pathos. I am a stand and a big bazaar and the mentored team shall pick only what they like. I am not a major stakeholder as I am not materially vested in the team’s success. I am here as a volunteer.

Acting, management and mentoring are alike at least in one more thing: filtering does not work. So how should I establish authenticity? I need to share my beliefs. How can I prove myself? By story telling again. After all, marketing is all about proof points, isn’t it?

When the team shares my beliefs and values, they understand my story and how is it relevant to their products and services, they are in the position to take some advice.

Teach? Share failures!

Merriam-Webster defines the noun “mentor” as a trusted counselor or guide. Having the right context from the team, being their customer at the moment and consistently with my beliefs and values, I am ready to share advice. What I did and how it worked. What I did and how it failed.

In my experience, the best way to share knowledge with others is to share your failures. When I succeed in something, I am seldom completely sure why I succeeded. When I fail, sooner or later I find out why exactly I failed. Failing gives me clarity and confidence. I am never giving up and I dare say that I learned to patiently and diligently study the failures I was part of, my failures or failures of my team.

That clarity and confidence also enables me to share it with the team. It is their choice whether they want to repeat mistakes of others or make their own mistakes.

Not that I agree with the failure worshipping, which seems to be a thing in the startup culture. As Tomas Sedlacek put it in his tweet, I strongly preffer trial-success than trial-error. I also believe in failing fast and measuring hard, which I will probably never fully learn.

And I am not as selfless as it may seem. There has to be something in this for me.

Why am I here today?

Mentoring is a learning experience, so first and foremost, I am hear to learn. Occasionally, I learn about new approach, business model or technology. I used to focus on that.

Today, I am here to train. To stretch my muscles in a different way than I am stretching them every day at work. If you ever exercised with a trainer, you know that your trainer is changing your exercise quite often. You are doing something else on Tuesday than you did on Monday.

Change is good as human body excels at adaptation and always finds equilibrium of achieving results with minimal energy. Human brain is no different and is actually great at building and making mental shortcuts. I am here to train active listening skills in extreme conditions (time is short), maintain an open mind and apply what I know on problems I do not have. I am here to push myself for patience, which is one of my biggest weaknesses.

And I am here to relax. Other teams and other people struggle with difficult issues too. Others are also trying to do what they believe in.

I am not alone in this.

Your Landing Page Sucks (Yes, Still)

/in Marketing, Startup Tools/by StartupYardThe Landing Page. Yes, in 2018, this is still an important part of your arsenal of marketing skills as a startup. That’s why at StartupYard, I still do a full-on workshop on just this topic, and why with every startup we accelerate, we drill these basic themes over and over again.

Why? Because the ability to write and execute an effective landing page depends on a very clear grasp of good marketing in general. A landing page is a “single serving communication,” or a piece of marketing that has to speak for itself, and be judged on its own. So it is also a great testbed for ideas, and seeing what works, or doesn’t work.

Since we face many of the same challenges with startups year after year, I thought it was high time to publish a post about the basic principles behind an effective landing page. These strategies can be used in many forms of communication (like email), because they focus on understanding the *why* of messaging decisions, rather than the *what* of any particular message.

What is a Landing Page?

For the purposes of this discussion, a landing page is a part of your website (or online product) where visitors “land” first. Depending on what kind of company you are, you might have only one landing page: your Homepage. Or you might have many. A blog post can serve as a landing page if it is meant to draw people in via search or social media.

Here are some examples of successful modern landing pages of different kinds. Take a moment and appreciate what about them is consistent and familiar.

In this discussion, we’re going to follow the KISS principle, and only talk about one kind of landing page, which is the single-purpose landing page, with one target audience, one message, and one call to action.

The Trust Pizza

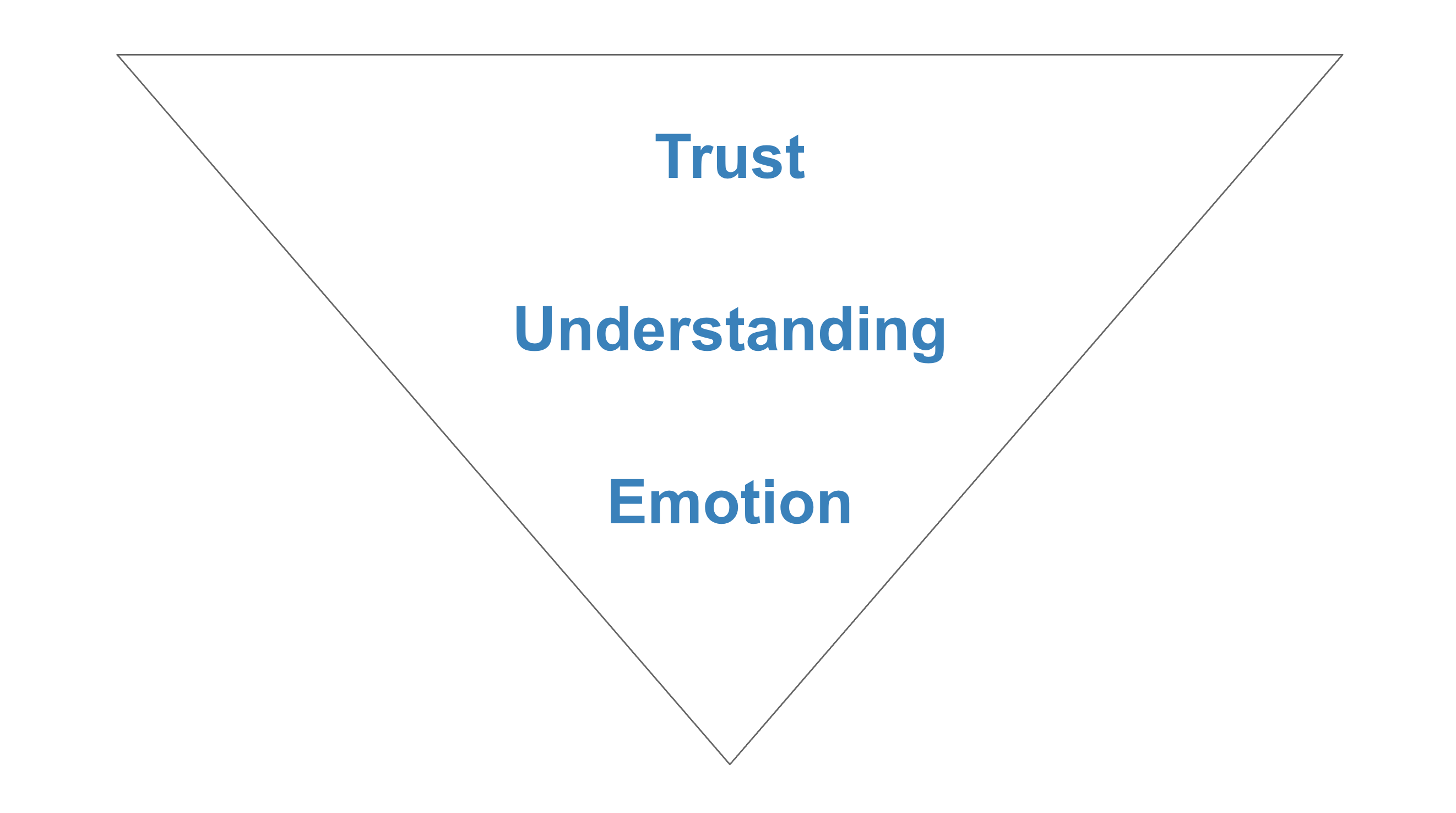

Over the years, I’ve worked as a copywriter on uncountable landing pages, and other single-use marketing materials for scores of startups. I’ve devised a very simple formula for determining whether I am being effective with a particular page.

Content is King, as we say. A great message is most important. But an effective message follows from the right approach. Having a formal structure that is designed to be foolproof is important in helping you shape a message.

My formal approach is simple. I call it the “trust pizza.” Here’s what it looks like:

What is important about the Trust Pizza is its shape and the order of ingredients. Follow this simple strategy, and you’re much more able to judge whether your landing page is likely to work or not.

-

Trust = Crust

The most boring but essential element of the pizza is the crust. Not only do we grab a pizza by the crust, we also use the crust to judge the pizza overall.

Just think about evaluating a pizza. If the crust is burnt, what does that tell you about the overall quality of the thing? On the other hand, if the crust is soft and inviting, then you know the pizza will probably be good. Looking at the middle of the pizza tells us very little about it: it might be good, but we can’t know.

The “outer layer” of a landing page is just like that. Trust is composed of every background element of your page. Do you have a header and footer? Do you have appropriate links and contact details? Is the font, color and any background image on-brand?

You should spend as much time on these details as you do on the central message of a landing page. These things tell us whether you can be trusted at all, much less believed in this particular case. Get them wrong, and forget about anyone taking a “bite” out of your landing page.

The trust crust also reminds us not to get too clever. At the end of the day, no matter how revolutionary the idea, a pizza still looks like a pizza. So it is with a landing page. The content should be interesting, but not *less interesting* than the format.

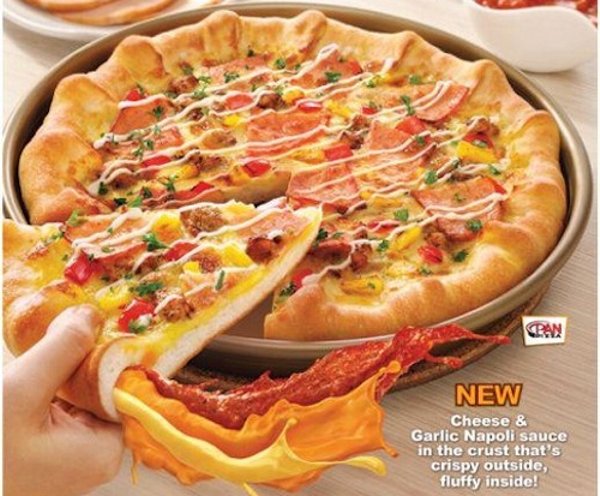

Not only confusing, but actually disgusting.

If you want to give the impression that you’re incredibly hip and modern, do so with the understanding that this may be the only message that gets across. I may admire a pizza shaped like the Eiffel tower, but I don’t want to eat it.

2. Understanding = Toppings

The “understanding” aspect of your landing page is the heart of the message. It is the information you want to convey. It’s often a number or a date. It’s a key point. If a visitor remembers anything about you, it should be this.

Of course when you order a pizza, the toppings are the focus. They differentiate your pizza from all other pizzas. Cheese and pepperoni is totally different from a cream sauce with BBQ chicken.

But remember: an effective pizza has only the right combination of toppings. Go too crazy, and you turn something good into something truly nasty. Burgers are good. Fries are good. Nuggets are good. But all 3 on a pizza are not good, they’re gross.

Adhere to the KISS principle (Keep it Simple Stupid), when choosing your toppings. If you aren’t sure how to blend two ideas together, then don’t try. Choose the most important one, and go with that.

Better a few good toppings than a mess of bad ones, right?

All of these things individually are amazing. All of them together are horrifying.

3. Emotion = The First Bite

Finally the good stuff. The pointy edge of your landing page pizza is the spot at which a customer will “bite.” So you need to give them a good reason to do so. You’ve presented an appealing crust, a nice set of toppings, and now you want a nice, crisp wedge shape to finish the job.

This is the Call to Action. The button, or other cue which should prompt a person to do something (take a bite of the pizza), and be led somewhere else on your website, or in your customer funnel.

The call to action is the simplest but often most important part of a page. It prompts the user with their next move, and at the same time must show them exactly what happens when they click the button, follow the link, or enter their information. The “ first bite” has to be rewarding enough: it has to be mouth watering.

The Pizza Shaped Landing Page

The above is a tool for planning and assembling the elements of your marketing message for a landing page. But remember that just as you must form a pizza from raw ingredients into a certain shape, so must you shape a landing page to be enticing and “edible.”

One of the keys here is “visual momentum,” or what I call the pinball effect. That is, the attention and visual interest of the page should eventually lead down to the place where you want eyeballs to be. It can’t *start* there, but it shouldn’t end somewhere else. No big exciting things to see off to the side. No distractions: just one bigger message leader to a smaller one, leading to a simple action.

In principle, you should try to keep the three key sections of your landing page organized in order of interest:

- The Headline

- The Body (or Subhead)

- The Call to Action

The Headline

The headline, while simple, should grab the most interest from the beginning. It is something bold and maybe unexpected. It is not, I repeat, *NOT* a list of buzzy words like: “Analyze. Evaluate. Innovate.”

That’s just lame folks. Your headline needs to be a statement about why you’re different. It should be something ripped straight from the “unlike” section of your positioning statement. It can even be negative: “Don’t Be Lame,” or “Had Enough BS for One Day?”

That’s an eye-catching statement. Something weak and defensive is not eye-catching. “We Care about You,” is not compelling. “Our Customers Come First,” is an eye-roll at best. Say something definitive about what makes you different, and more importantly, why your customer should even care.

Remember: the Headline is about letting the visitor know what they’re in for. It’s a signal of what’s to come. So it needs to be a strong one.

The Body (Or SubHead)

Here you have the most freedom. It’s toppings time! You should include numbers, or statistics, or outcomes that your product or service will provide. What’s the difference between a pizza you love and one you hate on sight? The toppings.

“Trusted by 3 of 4 Startups,” for example, or “Proven to lower your costs by 30%.” These are informative, direct statements about what the product is promising to do for the customer. They’re beautiful sausage and pepperoni, or olives if that’s your thing.

If the landing page is for an event or a sale, then it might be time to include the date or time.

Remember the It’s Not About You principle. This is not the time to explain that you are a bio-organic-cruelty-free-lactose-intolerant team of albino hemophiliacs who identify as lawn ornaments. The customer wants to hear what’s in it for them. You’re trying to tell them you’re using artisanal cheeses made by blind pagan craftsmen in the alps, but they want to know if the pizza is vegetarian or meat-lovers. They want the facts, not the fluff.

Now is also *not* the time to sell or urge action. Don’t jump the gun here. You’re being informative. You’re showing the meat of the offer, not closing the sale.

The Call to Action (Take a Bite)

Now you’re closing. The call to action is simple but very tricky. You want to accomplish a bunch of objectives at once, to some degree or another. You want the visitor to know a number of things:

- What am I supposed to do

- When am I supposed to do it

- What will happen

- When will it happen

And remember, this is a call to action that may be as long as two or three words. It has to accomplish a lot in that space of time. It needs to rely on context and build upon the preceding elements to do that.

But always consider the call to action in this context: Is it clear to the reader exactly what will happen when they press that button? And is what they think is going to happen the same as what will actually happen? As a landing page is meant to create a relationship, you need to start it off by delivering on what you’ve promised.

Don’t offer something in your call to action that you can’t deliver. Don’t lie. Don’t even get close to maybe being a little bit dishonest. Just don’t do it.

Here are some common “Call to Action Lies” to avoid, along with the reasons they suck:

- It’s Free! [But give us your credit card lol it’s not free]

- Start Your Trial [Actually give us your contact so we can sell you]

- Get it Now [But you have to wait a while]

- Get the Beta [When it’s ready if ever]

- Learn More [Just kidding lol buy now]

Instead, a call to action should do exactly what the user expects. If you want their email, say: “Enter Your Email,” if you want them to buy, say: “Buy Now, Save X.” If you want them to demo the product, then make the demo accessible when you say it will be.

Remember: If you’re thinking it’s a cheat, then your visitor is too. Don’t treat your customers as dumber than you are. Assume they’re smarter.

Stick to the Trust Pizza

Remember, whatever decisions you make about *what* to communicate, never forget the importance of *how* you communicate it. In my experience, more than half of the message is not the words you use, but rather their format.

Does it look right? Does it make visual sense? Is it weird or somehow off? These details make or break a landing page much more easily than a less than perfect turn of phrase. Stick to the pizza. Don’t reinvent it.

SY Investor Launches DOT Glasses: The $3 Glasses That Could Help the World See

/in Interviews/by StartupYardOver 1 billion people in the world need glasses, but can’t afford them or don’t have access to them. That’s why StartupYard investor and mentor Philip Staehelin launched a Czech startup – DOT Glasses – to try to solve this massive problem 3 years ago.

Today he believes they finally have the solution, and are about to launch large-scale production of the world’s first, one-size-fits-all eyeglass frames (which were designed by a joint venture of Mercedes-Benz and AKKA Technologies), along with a transformative lens concept.

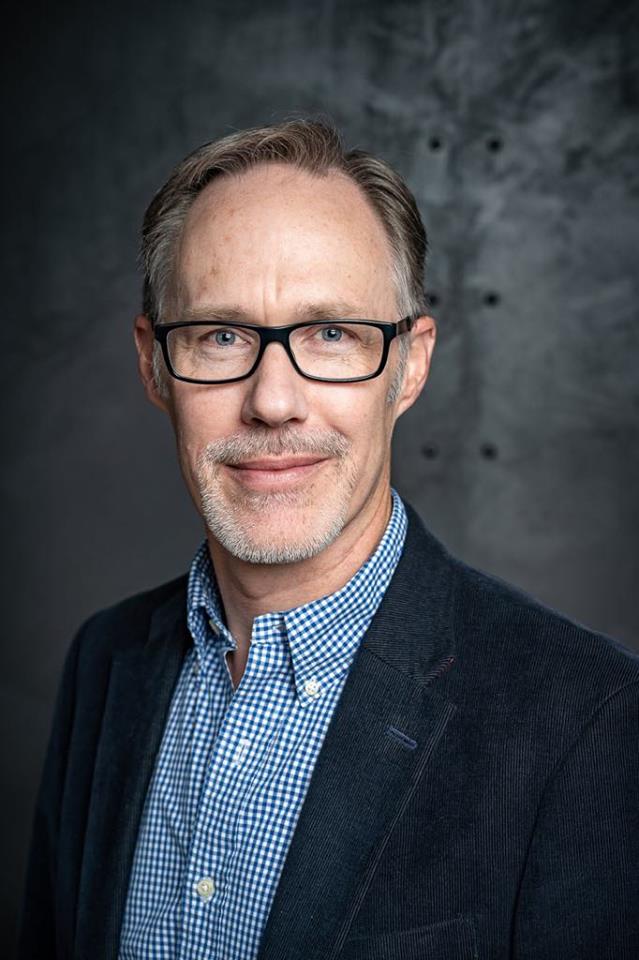

Philip is the former CEO of CCS, the former Managing Partner of Roland Berger, and an alumnus of many other international companies like Accenture, T-Mobile and A.T. Kearney.

Earlier this year, DOT Glasses received a “matching funds grant” from CzechAid (up to CZK 5m over 3 years), and they’ve recently won a place in the EU-funded Startup Europe’s Soft Landing program to India (called the “Ecosystem Discovery Mission”). They were one of the 24 European representatives selected for the program.

I sat down with Philip this week to talk about the launch of DOT Glasses, along with the crowdfunding campaign to support the company on hithit (you can check the link to contribute). Here’s what he had to say:

Lloyd: Why glasses?

Philip: There are a few parts to the story, of course. If you’re asking specifically why I decided to focus on providing glasses to people in developing regions, it’s just one of those weird coincidences that suddenly made me realize that a 700-year-old industry could still be disrupted.

If you mean, why glasses and why provide them to developing regions, it’s because I’ve long been focused on making an impact beyond my immediate “bubble”, and I was at a stage in my career where I wanted to use my time and resources to help those most in need of things we take for granted here in the developed world.

The idea specifically came to me while I was skiing, and it’s funny because at first it seemed like a pretty first world problem to have. I’m mildly nearsighted now (although I used to have very bad eyesight, and had laser surgery 15 years ago to correct my vision), so I wear glasses. I can do without them, but I like the world in sharp focus.

Philip Staehelin, Founder of DOT Glasses

When I ski, I don’t like to wear my glasses under my ski goggles, so I usually go without – which isn’t always good especially when skiing moguls. On the ski lift, I was daydreaming about buying some “off-the-shelf” lenses to pop into some specially-designed ski goggles, providing me improved (if not perfect) vision to make my skiing more comfortable. I didn’t want to spend money on prescription ski goggles – it wasn’t worth it, and it was a hassle – but I started thinking about what could be “good enough” vision and how I could stock some limited range of lenses on the shelf next to ski goggles, so people could just select what lens helped them enough.

The next ride up on the ski lift brought me a eureka moment. “Good enough” vision was all about smartly limiting the selection of lenses. It’s kind of like the 80/20 rule that’s prevalent in so many facets of life and business. 20% of the effort for 80% of the gain. 20% of the lenses to achieve 80% of the vision clarity. If it was true (and the implications came crashing down on me all at once)… it could transform an industry. But not the ski industry with a few million customers at best.

Rather, it could disrupt the eyeglasses industry for people in need. Actually, “disrupt” is the wrong word in this case, because more than 1 billion people need glasses but have no access to them or can’t afford them. So there is not a current player to disrupt. It’s more about tapping into a new, massive customer segment that has been unaddressable because of the challenges of costs, logistics, lack of optometrists, etc.

When I got back home, I started researching the issue. You may think, living in Europe, that we are drowning in optometrists, because they are on every corner of every major city. Actually we have something like 1 optometrist for every 3000 people, and about 60% of those optometrists are usually based in the capital cities.

On the contrary, in many underdeveloped regions, such as in parts of Africa, there are not enough optometrists to go around. In some cases, there are only a handful in an entire country with millions of people. In Ghana, there are about 50 optometrists for a population of nearly 20 million, and the per capita income is less than a dollar a day. Getting glasses can take a week’s travel and several months’ wages.

Which means that for a vast swath of the world’s population – glasses are either an unaffordable luxury, or they’re simply not available. If you have +/-1 diopter (also known as 20/40 vision), you can absolutely live a normal life. In the UK for instance, 20/40 is the required driving standard. But once you start getting past +/-3 diopters (20/250), it starts to become difficult to lead a normal life. I have first-hand experience, as I used to have -6 diopters before my laser surgery, and as a kid, I literally couldn’t find my family at the beach if I didn’t have my glasses.

That’s so interesting. Basically there is no existing market to help these people.

Exactly. Poor vision is the #1 health issue in the world, but almost no one talks about it. It causes roughly $230 billion dollars of economic loss every single year, but on an individual level, poor eyesight prevents people from learning in school, it prevents them from having a meaningful job (or any job), and it hurts families and communities. Poor vision literally traps people and families in poverty. But it’s been too challenging to treat poor vision in more remote parts of the world, even though the solution has been around for centuries.

So in the end I decided on a simple concept (I actually call it “maximum simplification”): a set of glasses that are both modular, and cheap, which can reach developing regions fairly easily, and don’t require a professional optometrist to be dispensed to the end user. All you need, to provide a pair of customized DOT Glasses is a very simple testing tool (that we developed), and the components of your individual set of glasses: the 6 pieces of the snap-together frames, and the right strength of lenses (which, by the way, are “left-right agnostic” – a concept we also developed, allowing for the same lens shape to be used as a right or left lens, which reduces lens stock requirements by half). The end result: robust, good-looking, glasses that are available to a buyer for about $3.

$3 is a lot to some people

Yes. If you live on $2 a day, then $3, comparatively speaking, is pretty close to what a person in the developed world would pay for their own glasses from an optometrist. We have worked very hard to make them as affordable as possible, and $3 is the lowest we’ve been able to get it. For those wanting to correct a less severe problem with their eyesight (e.g. -2 diopters), this price point may not be absolutely compelling, but for the more severe cases, it’s the best investment they will ever make. It will be completely life changing.

Why haven’t charities really attacked this problem before?

They have – there have been many projects targeting this problem, but none has been able to address all the issues needed to scale properly. Those that train optometrists are doing a great thing, but the world needs about 100,000 optometrists to bring the per capita ratio even close to a 1st world ratio… and they still wouldn’t be located in rural areas.

There are a lot of economic incentives against optometrists locating themselves in poorer areas. They go where people can pay more, especially if they are in high demand. That means you can train thousands of new optometrists and still have little impact in remote regions. They will go where the money is.

Others focus on delivering self-adjustable glasses with some fairly advanced technologies (two stand out: fluid-based lenses and Alvarez lenses). But in reality, these are over-engineered which keeps costs much too high. They deal with one shortage (optometrists), but they exacerbate another shortage (money). And they don’t look like normal glasses – they’re simply not fashionable enough.

Those that attempt to solve the problem by providing regular glasses as cheaply as possible still run into issues such as: huge stock of frames and lenses needed to address all of the combinations of faces (including pupil distance and ears distance from eyes) and eyesight requirements. This increases the cost of stock, and makes replenishing that stock much more complicated and costly, but it also requires a trained optometrist (or at least an optician) to measure the eyesight to a fairly granular level. All of this adds complexity and costs, which makes it impossible to propagate into more remote rural areas.

Also, I think one of the big problems with the all-charity approach is that they often fail to take the motivations of the people they are working with into account. If you develop real economic incentives for people to distribute the glasses as a product, for example, by supplying a few local people with the training and the equipment necessary to dispense them, then you are effectively creating a new market. That’s the reason we developed our own super easy testing kit as well, because at the end of the day, we want this to be a new viable small business opportunity for people in these remote areas, where previously providing glasses was not economically feasible.

That is why the glasses are not free to begin with. If we relied on charitable donations, we would also miss out on the opportunity to leverage the entrepreneurial energy of these local partners, who, let’s be honest, are going to understand their own local markets and customers a lot better than we do.

This is really the core failure of many NGO projects: they don’t really consider the long-term incentives of the participants and recipients of their help. Of course, not relying on donations also allows DOT Glasses to scale much faster than other organizations, as the business model is sustainable and the revenues are reinvested into growing the footprint to help more people. The more we can sell, the faster we’ll grow. We just need to “prime the pump” with donations and/or social impact investment in the early stages in order to build out our first networks.

So you’re not a charity.

No. We have charitable intentions (and we’re a true social enterprise), but I also believe that it’s in a way disrespectful to people in economically challenged regions to assume that they are not motivated in the same way that people are in developed regions, by the opportunity to pursue success and prosperity with hard work. That’s why we believe end-users of our glasses should be paying for them, and the profits from that activity should benefit the local economies as much as possible. Ultimately, that is the way to help these regions develop.

Also, in many cases, charitable activities can have a detrimental impact in the area they’re trying to help. They may end up hurting developing economies, even though they have the best intentions at heart. Think of food charities that end up displacing local farmers who can’t compete with free stuff. That’s a real problem with charities, and one that is rather insidious.

Even sending volunteers to teach in slums can have negative consequences, because the local government starts to depend on the free handout (in this case, education) and doesn’t develop a properly functioning, stable educational infrastructure of its own. Which means they don’t care about creating their own teachers, and those few teachers that there are may actually have lower salaries because they’re competing against “free”.

With our work, we hope to create microbusinesses, with the help of microloans if necessary. We want to have entrepreneurial people start up their own eye care businesses. In the process, they create a better life for themselves and their families, but they’re also selling a new lease on life to those who can’t see well. And it’s been proven, that there is a tremendous increase in productivity when someone gets their poor vision corrected, which means additional wealth creation for individuals, families and communities. It’s a true virtuous cycle.

You spent a career as an executive in big corporations, as a consultant, and finally as an investor (including in StartupYard). What would you advise someone like yourself, who is thinking about a career shift toward charitable/entrepreneurial work?

It’s a great question. The road from the boardroom to developing DOT Glasses for remote regions of the world was a pretty long and winding one. But the fact that it was long and winding is important, as I learned new things from every role I ever had. Small things and big things. I became more well-rounded, and I could see the world from more angles.

I’m a huge believer in cross-pollination of ideas between industries, between companies, between countries, etc. For example, I brought a lot of my mobile operator experience to my role as CEO of a large alternative payments company, because both had a lot of B2B and B2C customers, both needed customer care, both needed direct sales, both were concerned about customer churn… and in some cases the mobile operator approach could be adapted to create a better solution for the payments company.

This isn’t a unique experience obviously, but the corporate world is set up against this to some extent. They want to hire people with experience from their own industry. But I went through a few different industries, as well as through consulting (which teaches you a lot about how to structure problems, organize projects, analyze data, and find the core essence of the analysis), and I started using that breadth of experience to mentor startups.

Startups (especially with young founders) often know a lot about their technology, their market dynamics and perhaps a few other select bits of information – but they often lack the big picture. They also often lack some key skill sets that they will need, such as sales, finance, and strategy, not to mention, they have no idea how to talk to the corporate world (although I admit I’m hugely generalizing).

So I help them with that. But perhaps even more important than providing some insights into missing skills, is providing cross-pollination. It’s all about identifying new opportunities (even new tangents) that aren’t obvious. It’s about synthesizing new value by bringing together entirely new elements. Which is what I did with DOT Glasses.

Coming back to part of your question though, the answer is to strive to become a cross-pollinator. Constantly learn new things, challenge yourself, get out of your comfort zone as often as possible, get out of your corporate bubble, and go out into the world and do things. Mentor startups, work in a charity, join a business club – but if you do it, do everything actively. Make an impact. Don’t be passive, because then it’s just a waste of time. I like to say that “life is too short to do just one thing”. I believe in side interests. I believe in planting lots of seeds and seeing what sprouts. And eventually one of those things can grow into something bigger and more beautiful than you could have imagined.

But don’t forget the lessons you learn in the corporate world about pursuing long-term economic interests, including your own?

Yeah, that’s right. Social impact work is not necessarily charity. We don’t just give, we also look for sustainable opportunities that can grow the overall economies we are focusing on. That in the end is a benefit to us, and to those regions. In my view, there are many, many activities that are currently approached with a “charity” mindset, that might be better served by a social impact, entrepreneurial mindset as well.

Hey, this isn’t rocket science here! We all know the saying: “give a man a fish and he eats for a day; teach a man to fish, and he’ll eat for a lifetime.” Well, it’s not just teaching is it? Make someone your business partner, no matter what it is they’re doing, and make it mutually beneficial, and that is going to create opportunities for you both.

How do you think corporate officers, like you were in the past, can better contribute to this kind of sustainable social impact?

Let’s say this: I think it comes down to really trying to understand, and develop a respect for the people you are trying to help. When I think about social impact, I think about not only looking at ways of improving someone’s life, but also improving my own, and the lives of those around that person. That comes back to you, in the end. There is a part of social impact that should be “selfish,” in a way. I am doing this because I want to live in a better world, for me as well as for you.

I think it is a danger among those of us who enjoy some material success, that we begin to imagine that we are giving and no longer taking anything. However in most charitable activities that just isn’t true. We are taking a lot, in terms of what matters to us: respect, reputation, the feeling of doing good works. That is something of value. You should always be aware of what motivates you to do what you do.

Again, nothing wrong with feeling good for giving back. But I would encourage people to go further than that, and to think about how their actions really tie back into their own lives. This is how we empathize with people in the real world.

If I am helping someone in a remote village in India to see better, then how is this affecting my own life? I can tell you, it does affect my life. Leaving aside that each individual with the proper tools in life has a chance to change the world, to be the next Einstein, I am also helping to make sure that this person is being economically productive.

If people are more economically productive, it is more likely that they will be prosperous, and so will need less support in other ways. Eventually, developing regions become developed, and I can enjoy the benefits of that development in my own life. That is a prosperous cycle, and if you don’t actively look to see it, I think you lose sight of why you’re doing what you do. You may end up not really respecting the people you’re trying to help.

What have you learned from this that you didn’t already know? What has surprised you?

I’m an inventor at heart. I have lots of ideas. But I have learned something really new in the process of moving this project past “idea” stage, and into realization.

What I discovered is that the true “innovations” that end up happening are not only around the idea itself, but rather the things you have to invent in order to get that idea to work. What I mean is, the “solutions around the solution,” are actually where a great deal of the creative work happens.

So I start out with the lightning strike about “good enough vision” which creates a transformative lens concept. But to realize the potential of the lens concept, I had to work very, very hard to develop one-size-fits-all modular glasses (only my 3rd industrial designer cracked the nut – the first two didn’t find a solution), because I realized that the combination of those two elements could be the magic bullet to solve a vexing problem that no one else had managed to solve.

But after I had the glasses, I realized I needed some tools to facilitate the streamlined process I was imagining, so I had to design a vision tester and a pupil distance measuring tool. And then to bundle all that together into one “kit”, and designing an end-to-end process around that kit in order to get the glasses to those people that needed them… it was one problem after another that had to be addressed.

Each step required an innovation, but the innovations built on each other. Would someone have designed my pupil distance measuring tool without my modular glasses? No. But they were required for the entirely new ecosystem that I was building. So building the entire ecosystem took much more time than I expected.

So in the end, the work is more creative than the ideation.

Yep. It is. That’s something you can’t know until you try. I’m happy to have found that out, because being really creative and solving real problems every day is how I like to live my life.

If you’re interested in contributing to the DOT Glasses project, you can do so today by clicking below and pledging to their crowdfunding campaign:

Notes on Scaling: Building the Right Team

/in StartupYard News/by StartupYardTeam building isn’t easy. The other day, one of our founder alumni was complaining to me about a problem he’s been having in his growing company. The problem is that as the company grows, he is finding it very hard to find people to join the team who feel as “engaged” with what the company is doing as his earlier hires.

He described what happens with his most recent hires: they go through the interviews, the onboarding process, the initial training and background on the product and train for the role they will play in the company… and then they lose interest or quit. He described a batting average of less than 1 in 3 new hires who “make it” on his team.

What he expects is what I think most Startup founders come to expect, even long after that expectation may be reasonable: that new hires be as excited about their business as they are, and that they each bring a creative energy to the team that contributes to the whole in an important and unique way.

It reminded me of the story of almost every founder I’ve known who grew a company beyond a certain point. Mergim Cahani, in his last interview with StartupYard, told a similar tale.

Finding the “Right Team”

Of course there are some aspects of this problem that are beyond a founder’s control. You don’t control the job market, for example. When unemployment is low, people may be less desperate to get a job, or stay in a job once hired.

However, in the interest of focusing on things we can control, I’m going to go through a few ideas for the founder who is finding his or her later hires harder to retain or to motivate. I’ve seen these approaches work among our own startups, although you may find they don’t fit your needs in every case.

1. Hire Contractors for Jobs that Won’t Scale

While you’re busy looking for the perfect employee, you may miss out on the perfectly adequate contractor. Some founders get so focused on the idea of team building and culture making, that they forget the immediate reasons they are looking for talent is to get specific things done.

One of our alumni recently told me about how he wished, looking back, he had hired more contractors as he was scaling the business. He realized, too late, that he had hired a number of people with the idea that they were each individually a good fit with the team, and would be long-term assets to the company. But when a pivot in the business was necessary, their jobs could not be justified in the short term.

He ended up having to let people go after making a significant investment in finding the right people for his team. That caused not only a disruption in the company, but also a good deal of pain for the core team, who lost coworkers they cared about.

There is always a danger in under-investing in your team and culture, but there is also a danger to over-investing. Some jobs may simply be better left to contract workers who are not expected to become a key part of the team.

Contractors are not only easier to work with in the short term, but they may have a mentality towards their work that the company can benefit from. A focus on getting things done quickly and correctly can be important as an antidote to mission drift within a small team.

2. Question Your Typical “Hire Type”

The definition of insanity is trying the same things over and over, expecting different results.

An interesting story one founder told me was about this very problem. He had been hiring mainly younger employees, with the idea that they would bring “creative energy” and “spirit” to the company thanks to their lack of experience and their youth.

This is the “fresh eyes” idea, and it can have a lot of merit. Many CEOs focus on hiring people who are “unspoiled” by previous experiences, and can bring positive energy to the group. The problem for this particular founder was that the strategy wasn’t working. New hires didn’t contribute much beyond what they were asked for specifically.

The other problem was that the actual work he wanted these people to do was not that intellectually challenging or difficult. The result was that new hires were not as excited or as eager to contribute as he hoped.

“They’ll all so timid,” he told me. “They don’t even ask questions when they should. They don’t know how to express any interest in what we’re doing.” Anyone who has been the new kid at a school will know that feeling. Being young and fresh may give you perspective, but it doesn’t necessarily make you ready to share.

I asked this founder, “why don’t you hire someone older? Maybe even someone near retirement age?” The thought had never occured to him. Yet, someone with a lifetime of experience may be just the right type to do a job. A startup with an average age of around 30 may lack the life experience of somebody who has had a career, and may be less ambitious or restless than a younger hire.

If you’re hiring for a role that doesn’t require up-to-date technical abilities, then there is something to be said for hiring someone older, at the end of a more humble career, rather than at the beginning of an exciting one.

3. Reconsider Worker Incentives

In the same vein as the previous point, consider also that a person hired as Employee No. 3 is not the same type of person as the one who is hired as Employee No. 30 or beyond.

Namely, the bigger you get as a company, the less attractive you are to risk-taking hires who are interested in equity participation, and the more attractive you are to the kinds of people who are looking for a steady paycheck more than the opportunity to be in on the ground floor.

Yet some startups continue to incentivize their later hires in much the same way they incentivize their earlier ones. The problem is that offering someone equity, or the “opportunity to grow in your role,” is less meaningful the larger a company becomes. Employee No. 3 knows that there is room for advancement if the company is growing. Employee No. 30 may be less sure of that. Employee No. 300 may not believe it.

Yet if we step back and recalibrate the incentives for new hires, we can find more relevant motivators for a different kind of person to hit the ground running in a young company. If you’re hiring for sales, for example, the opportunity to make bigger commissions may be more attractive than an equity stake. If you’re hiring for a technical role, then goal-oriented compensation schemes may make more sense.

Don’t be afraid to experiment with new incentive structures for newer workers. The strategies that work for the earliest team members may not work later on, as the company gets bigger.

4. Hire People Smarter Than You

A friend of mine once told me: “Maybe you’re a one in a million genius, but on the other hand, there are a thousand more like you in China.”

It may be hard to admit to yourself, but you’re probably not good at everything. Hiring people who are smarter than you is a good practice for building a team that can master new challenges together. There are many kinds of genius, and many kinds of geniuses. Recognizing ways in which people are even smarter than you are can help you hire and motivate those people to contribute to your company.

In a sense, this point is more about your mentality than about your choices. If you are looking for people to hire who are smarter than you are in some respect, you’re likely to find that there are many ways in which potential team members excel that you may have been undervaluing.

Ask yourself with each candidate: how is this person smarter than I am? Maybe they have a better “EQ” (Emotional Intelligence), instead of a higher IQ. Maybe their genius is in art or in the sciences. The deeper you dig with people, the more likely you are to find some area in which they far exceed your own abilities.

A CEO who recognizes and values the talents of other people is more likely to use those people well, and make them feel valued along the way. So hire people smarter than you.

5. Hire “Failures”

Simply put, hire people with all kinds of experience. Hire people who have started their own businesses and failed. Hire people who have made mistakes, and learned from them. Hire people who aren’t from the best schools, or who don’t have the most experience.

Data shows that the average worker today will hold about 15 jobs in their lives. That’s over 3 more than the average reported by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics in the 1960s. Today, the average length of employment has dropped in developed economies to under 5 years.

What that means for you as a growing company is that you’re likely to see more turnover in your team than a small company 50 years ago. However, you’re also likely to be able to hire people with a broader set of experiences than before. It doesn’t necessarily follow that someone who has left a job after 5 years or less has “failed” at that job. Still, it’s likely they’ve made mistakes and earned experience your company can benefit from.

The tech industry practically fetishizes failure, but only failure of a certain kind. Never personal failings. Always a failure of reaching too high, and striving too hard. Never a failure caused by a simple lack of knowledge or inability to compete.

As economics author Malcolm Gladwell noted in his seminal piece on college admissions, and later in his book The Tipping Point, the average graduate of an Ivy league school like Harvard or Yale fares no better in the long term than a similar student who chooses to go to a lesser school (or is not accepted to an Ivy League school). In fact, long term, the effect on individual performance of being placed in “prestigious” surroundings and being compared to ever more successful colleagues is to cause individual productivity to drop.

The thinking goes: if I always succeed, and yet others around me are always better than me, then I must not be worth as much as they are. The “little fish” syndrome that high performers experience can extend across their whole careers. Michael Lewis, another economic writer, noted in Flashboys: A Wallstreet Revolt, that high performing software engineers at the most prestigious financial firms like Goldman Sachs were typically paid less than their lower-performing counterparts at lesser firms.

The reason? The competitive environment in high-profile companies made these employees less aware of their value to the company. In effect, those who failed to get these jobs, or who failed to stay in them, ended up benefiting financially from not being employed in the top firms. In failing at some point in their lives, these “lesser” individuals learned something their top-performing peers did not know. They learned how to value themselves.

Michal Kratochvil: Budgetbakers CEO Talks Profitability and Pivots

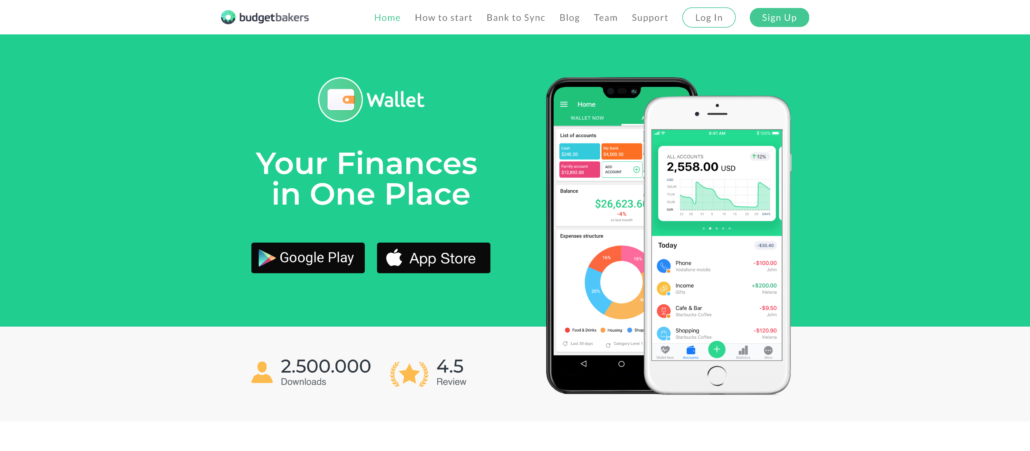

/in Interviews, StartupYard News/by StartupYardMichal Kratochvil is a StartupYard investor, former head of Accenture Consulting for Central Europe, and currently the CEO of StartupYard Alum and popular personal finance management platform BudgetBakers (SY Batch 5), a role he took up in 2016.

BudgetBakers informed investors this month that they are now cash flow positive and, in fact, that monthly revenues had nearly doubled in just a few months, after 2 years of mostly steady growth. This news came just months after BudgetBakers nearly halved the size of its team, and pivoted to focus developing some the flagship app’s core features (like integrations with banks).

I sat down with Michal to talk about the last 6 months at the company, and what he’s learned from the ups and downs of running a tech startup for over 2 years. Here is what he had to say:

Hi Michal, so you’ve been with BudgetBakers for over 2 years now. What were the surprises? If you could go back to the beginning, what would you do differently?

Michal Kratochvil, CEO at BudgetBakers since 2016

I should say I did everything perfectly, and everything went according to our brilliant plan, right? :laughs: Ok, there are always going to be things you would want to change because you know the outcome, but this is cheating. If you’re asking how I would have changed our general approach, there are a few things I would do differently. I would try and make some of the “surprises” less surprising.

How would you do that?

Let’s be concrete. When I joined BudgetBakers, Founder Jan Muller and I explored many options as to where we could take the company. I spent a few months getting to know all the possibilities, and coming up with plans.

We decided to focus on a couple of core activities. One of them: continuing to develop our B2C product, which was already enjoying a lot of popularity, with tens of thousands of active users (it was then in Version 2, we are now up to Version 6). Today we have added tens of thousands more, and recurring revenues have grown from nearly zero, to tens of thousands of Euros per month.

The other activity was to explore the second pillar of our business, which I believed was going to be our partnerships with financial institutions, particularly banks. There are a lot of opportunities for personal finance management software companies to help banks and their customers. Banks are very much in need of new ideas and new ways to serve their customers, and we have a personal finance product that people choose to pay for. So I think we have a lot to offer, either as a white label, or in some other form of partnership.

Of course, working with a bank is a difficult process, and matching up and actually managing to make a deal at the end of the day is very tough. They have dozens of priorities, you have just a few.

What I think is interesting is that my advice about the former (B2C), and my advice about the latter (B2B) will slightly conflict. I believe now that we had to be more patient when it came to developing our B2C product, particularly in our release schedule, and I believe we should have been less patient in our B2B activities with partners.

Why more patient with the B2C product?

You know, I think it comes down to just human nature. We keep making the same mistakes, because we don’t really change that much as people. We are startup guys. We want action! Get the products out the door.

When I joined the company, I saw that our dependence on platforms like Google Playstore and iOS App store was a vulnerability. You are getting most of your business directly from these places as an app maker.

What I did not expect, which I found out quickly, was that your fortunes can really hinge on these platforms on a day to day basis. When we went from, I think v2.x to v3.0, it was a major shock to me how violent the reaction was from the user base. Instantly, your rating drops from average 4.5 stars, to under 4. Closer to 3. Then slowly, over months, it starts to go back up as you fix some of the things you got wrong, and customers sort of get used to some of the changes.

BudgetBakers provides a complete personal finance solution for individuals, families and small business.

Why does this happen?

Please, if I knew why, then it wouldn’t happen. :laughs: I think people just do not like change. When we make major changes to the apps, even when we have to make them and the long-term results will be better for the users, still nobody likes change. You moved that one button, you disrupted my flow in the app, so I’m pissed. One star. That’s what happens.

Not to mention, there are bugs that appear when you make major releases. This also provokes a harsh reaction, especially from your biggest fans.

So how would you try to be better at this?

What I would do differently, which frankly I have still not gotten 100% right, is to make us a bit more patient with the release of a big new version, and try and take the release in smaller steps. Try to create more of a transition in the product from one version to another, and game out more of the steps needed to get from here to there.

You need a bunch of things to work really well in order to push a major release. You need to migrate data and settings, you need to create a path for the users to move from the old UI to the new UI, and still be comfortable with the product.

We do testing, and we try to get everything working, but if I’m being honest, the temptation is always to push too fast, and to get the release out before it is really ready. I am saying this, knowing that we will still want to move too fast in this regard.

Do you think you will ever get the timing exactly right? This is a problem even for huge software companies.

I think it will never be totally right, but it can definitely be better. What you do not want is this sudden shock reaction from your userbase, who are suddenly giving you one-star reviews because of what is really a dumb mistake, or a series of small errors that can be avoided.

As you grow in maturity as a company, you have to get better at this, because your customer base is growing also. It is starting to include people who do not have patience for these kinds of issues. They don’t know the history of the product, and their level of engagement is not as deep. You can become really invested in big changes to the product, and then fail to explain these changes well or to justify them to the users. Then you have problems.

We are no longer in the land of early adopters at BudgetBakers. Our hardcore, long time users, while they are still really important to the way we think about the product, and test the product, are not the average user anymore. They become increasingly the edge case, and this means you need to be casting new hooks and talking to less engaged customers as well.

I would say our power users are 20% of our paying customer base. So the 80% are the silent majority, and these are the people who you need to aware can very quickly change their mind about you. These are also the people who will not tell you what they need. You have to really dig in to understand them. They won’t spell it out for you.

Your 20% might be very vocal about changes, but they will not walk away either. What they tell you is important to them, may be important, or it might not be. The more casual users, who are seeing you in a less personal way, can be less forgiving. If you don’t give what they need, they go elsewhere.

Part of growing your product maturity is to understand that your customers’ actions are more important than their words. If people complain, and yet we can see that they are using the product, maybe even using it more, then we should take this under consideration. Everyone likes to complain about changes.

[Author’s note: at the time of writing, the current rating for BudgetBakers’ flagship app, based on nearly 89,000 reviews, was 4.5 Stars on the Google Play Store]

One of the biggest mistakes you can make is to deprecate a popular feature without a real replacement.

Yes! That is a huge danger. Worse if you really don’t appreciate how important something is until you take it away from your average users. That can be surprising. Every time we do a big change, it does surprise me, even though I know now to expect this.

Just spending a little more time on something and getting beyond “it works, get it out the door now,” is what we have to work on. Just sleep on it, and play with it for a little longer. 3 weeks more of testing. I keep saying this, but every time the temptation is the same, to rush the release. You want those new features to be out in people’s hands, and you want that feedback.

It’s a bit of an addiction, maybe. We can’t stop the cycle. It’s like the binge and the hangover. You load so many things into the big release, and then you deal with the hangover, which is negative feedback, complaints, etc. You feel that all the way down your funnel, for weeks and months.

In Node5 where we work, as you’ve seen yourself, there is a sign about “the better is the enemy of the good.” This is it. We always want to be better, but sometimes you just have to be good.

Mentor, Investor, Startup CEO: Michal Kratochvil talks about life at StartupYard

StartupYard investor, mentor, and CEO of StartupYard alum BudgetBakers, Michal Kratochvil joined the world of startups after a career in corporations as Managing Director of Accenture Consulting in Prague. Michal gives us an idea of how working with startups has changed his view of business in the past few years, and how he became a believer in Acceleration.

Posted by StartupYard on Monday, January 15, 2018

In 2017, Michal spoke on video about his experiences as a StartupYard investor, mentor, and CEO.

So be more patient with your release schedule. What about being less patient with your partners?

Let’s say not “less patient,” because you have to be persistent in this business. Instead, let’s say: “more opportunistic,” or “less confident,” about the likelihood of any one deal working out.

A big danger for any small company, particularly just after raising a seed investment as we did, is that you commit too many of your resources to one deal. You can spend a lot of money and effort working on this one deal, and if it falls through, for whatever reason, this is money that is not coming back.

This can be just bad luck. A deal can fail to happen because somebody changes positions, or gets fired. That happened with us. The deal we hoped would happen just didn’t. It not in our control, nor in theirs. It just didn’t happen.

So if I had this to do again, I would remind myself that you need to be constantly building up your pipeline of opportunities. You can’t stop building a pipeline, because when you stop, you inevitably become increasingly dependant on what others decide to do. Basically, more dependent on chance and luck, because you aren’t making the opportunities actively.

When you are working towards one particular deal, you get focused on the value this deal can provide for the company. However, that deal is worth nothing until it is signed. Until it is signed, you need to be constantly working on alternatives in your pipeline. That is a best-case scenario, which is that you have to tell partners, “sorry, we made another deal.”

You know, going back to someone who you dropped 6 months ago means you start the process all over again. You can’t afford to do that. They can move on in that time. You are basically starting at zero, so you need to be building that pipeline until the moment you make a deal.

Do you have a new appreciation for the role of luck in this process?

Yes, in a way. Of course luck doesn’t matter if you don’t do the work. We did well by really investing in our technology and building up our products from the ground up. We did the work. At the same time, this work in the case of this particular partner, didn’t pay off. It was bad luck.

That being said, this same hard work can pay off in ways you don’t expect at first. When this deal fell through, for example, we had to make a really hard pivot to focusing on growing our B2C product faster, and adding more features that we were very sure would attract more customers.

As a result, we sat around really asking ourselves: what can we do in a matter of days or weeks to increase the sales of this product? That led to some big changes, and as we’ve seen, some dramatic results in the end. Our revenues basically doubled in a few months.

We absolutely could not have done this if we had not been investing well in the development of our backend. We would not have had this resiliency that we had, and the pivot would not have worked without that.

Still, and again, there was an element of luck here as well, in that in the moment we turned away from the B2B business, there was a new opportunity in the B2C space that was just opening up. I’m talking specifically about the ability to connect our user’s accounts directly with their banks, so that they can get a view of their finances without doing any manual data entries. This was the perfect moment to really focus on that functionality, and as a result we made a deal very quickly with a big data provider to connect with two or three times more banks than we had before.

What have been the hardest moments in the transition to a cash-positive operation?

When we had to make this particular pivot, we had built our team with the hope that we would make this B2B deal. When it didn’t happen, we had to change the team. Letting people go and shrinking the team has been very tough on us. No easy way to say it. It is not fun.

I have plenty of experience with this, but quite honestly, it is not something you want to get used to. It is not nice, and it does hurt.

You don’t have to talk about that…

Well, it is fresh, but also there are some things I think we can learn from it. We can do better, always. I want to be clear first of all that I still believe in each individual that we had to let go. This was not about them, but about where we needed to be as a company. That is important to emphasize for me: it was never a mistake to work with any of them. If I could keep them all, I would.

Have you learned something you didn’t know about building a team?

Yes, I always believed that you need to consider several things when hiring someone. First: you need to consider the immediate goals of the company, and the talent you need for those. Then you need to consider the long-term health of the company, and just as importantly, you must always consider the personal development of the people you hire.

I believe strongly in this, that you must invest in people when they join your team, and also in the case that they may choose to leave, or you are forced to let them go. Still, I believe we owe it to people who we hire to see that they land in the right place. I’ve put a lot of effort into making sure that these people have their next steps and are secure. That’s something I believe we promised them from the beginning, and you must keep your promises.

I’ve been managing people for 25 years. There are those managers who keep their promises and commitments, and those who don’t. If you do keep commitments, and if you are focused on the good of your employees during and after their time with you, then you are going to have a better time in life, and an easier time finding people to work with you.

But hiring for a startup is different than hiring for a big company…

Yeah, because the promise is a bit different. You are building this little family, and you’re asking people to be more flexible, and find their role in the company over time, instead of having that pre-defined by an HR department or something.

That means to me that I have asked people to have faith in me and the company, and I have put faith in them as individuals. I could not sleep at night if I did not believe I was doing all I can to help those who have helped us. That is a core commitment that you make to people as a leader. You must follow it through.