Anatomy of A Bad Idea

Why Some Startups Are Doomed to Fail

Last week, StartupYard finished its selection for the first 2015 acceleration round. We can’t tell you anything yet about the teams that we’ve chosen to invite to the accelerator, but we can say that it was a great experience to meet the teams, and the final choices were very difficult- much more difficult than they ever have been before.

Often, it is very tough for an evaluator to separate his or her impression of the team being evaluated, from the impression of the product. As I’ve said here often: the team is almost everything. We have taken, and will continue to take, teams that are working on products we don’t necessarily think have found a product/market fit. Sometimes it’s up to the teams to convince us that their ideas will work, and sometimes it’s up to us to convince the teams to change directions.

What we don’t do, is take teams we don’t believe in. This is not to say that we never have taken teams that presented us with certain doubts. But even those doubts have almost always been justified in the end. The biggest point of failure in startups is not the product design, the marketing, or the investment plan, but the willingness and ability of the team to adapt and persevere.

Having now read over several hundred applications, and heard scores of pitches over the last year, though, I’ve identified a few common issues among the teams we have rejected. These are not hard and fast rules, and they’re very subjective. Plus, almost every team we accept *has* at least one of these issues to some degree. The difference is that we believe in the team enough to give them the chance to overcome it. Here are a few of those issues:

It’s a Feature. Not a Product.

By far, the most common product issue with Startups that are rejected from StartupYard’s final rounds of evaluation has to do with the strength of the product vertical. It’s one thing to help a strong team to focus its efforts on a smaller market than they envisioned originally. It’s quite another to ask a team that has devoted considerable energy to a niche, to take the wider view of their product category. Many strong startups *do* start with relatively narrow market approaches- but they also bring ambitions for expanding into new areas. Sometimes, however, we see startups that are so focused on a particular aspect of what they do, that they’ve effectively lost sight (or never had sight) of their place in the bigger market. A common question for us when we meet these teams is: “what happens when X (Google, Microsoft, Apple, Facebook) copies this feature?” Many a potential startup has been crushed by its functionalities being added to an operating system or platform it depends on to survive.

Having a feature that mimics your product’s behavior doesn’t have to be the end of your company. There wouldn’t be successful calendar apps, email services, browsers, timers, messengers, and 100s of other services if that were true. But if your product category is so narrow that your customers only identify it with a specific functionality, rather than a whole market, then you may have problems.

We have had to reject very interesting projects for this reason: the team has just worked so long and hard on a single feature, that they have become unable to envision its place in the market as a whole product. Because no matter how ingenious a particular feature is, and no matter how useful it may be, it has to be something that can be marketed and sold. Otherwise, it will inevitably become a part of another product that can be.

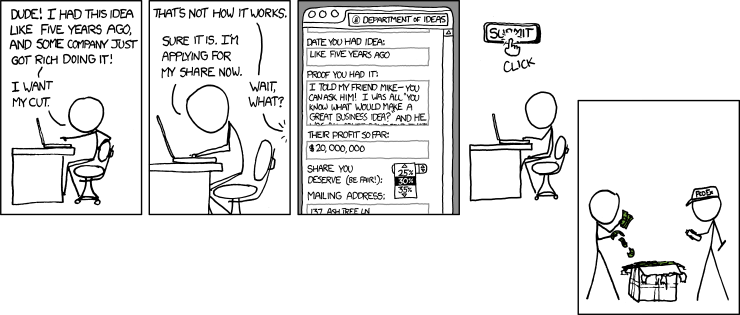

Doing it For the Wrong Reasons

Not everybody in tech wants to be a Steve Jobs or a Mark Zuckerberg. If that’s what you want though, get in line. There are probably people a lot smarter than you with the same ambitions. But these luminaries, and the thousands of others who have made real, deep impacts on the world of tech and business, did so by channeling their passions, for many years, through wise, careful business decisions that accomplished goals unrelated to making mountains of money. The money is the by-product, a useful sideline to their missions to change the world for the good. And those two gentlemen both gained some notoriety for not caring that much about it to begin with.

If you want to be famous, you’re much better off going on auditions for television dramas (or worse, reality shows) than you are starting a company. In fact, starting a company in the hopes of being famous is sort of like trying to invent a new camera in the hopes of becoming a moviestar. There are shorter routes to fame, and ones that don’t involve wasting the time and energy of dozens of other people.

It’s Not a Business

I don’t think many people would argue that any modern day startup founder was smarter than Alan Turing, or that any CEO of a large tech company was a brighter mind than Alexander Graham Bell. Both contributed enormously to the world that we now work in. But neither Alan Turing, nor Bell, were really businessmen, and though they respectively invented modern computing and telephony, neither profited much from it during their lives.

Some of the most creative and interesting startups we talk to are like this. They have engaging, intriguing ideas, and they are good at talking about them. But when it comes to laying out a plan for growth and profitability, it becomes clear quickly that what they have is not really a business. It *could* be a business, but even though they’ve done incredible intellectual work in developing their ideas, those ideas are about as relevant to starting a business as Einstein’s work was to the Manhattan Project. Einstein discovered that nuclear fission was possible. The skills needed to do that were unrelated to the skills necessary to make a nuclear bomb, or building a nuclear energy plant. A startup is not that different. The world needs visionary programmers and thinkers to come up with ideas we couldn’t previously imagine- but the world will take advantage of those ideas in ways that those thinkers may not have the skills to help with. The cruel reality is that most inventors have an uphill battle to fight, if they want to capitalize on their ideas. And history is full of visionaries who failed to profit from their own ideas. The perfect startup has visionaries and executors in the same team, but few have enough of both.

Local Niches are not a Path to Global Markets

We see a fair number of startups that aren’t exactly “me-too” products, but that don’t exactly have global appeal either. These are the niche products: the ones that work for reasons apart from their core functionality. They appeal to a specific type of person that doesn’t want to buy a mainstream product. . A niche product can be highly successful, with a devoted fan base. Given time, a niche product can spread itself to all corners of the world, finding like minded customers in many diverse cultures and markets, and binding them together over a single idea.

But local niches are something else. If a product is designed to serve a single market, and a single pain in that single market, and it doesn’t lend itself in any way to growing its userbase, or expanding its territory, then its days are probably numbered. Either international competitors will slowly eat the ground from under them, or the circumstances of the local market will shift, and customers will have fewer reasons to use their products. Having done all the work to develop the market for their product, the local niche company will quickly be challenged by better, shinier, newer, cheaper products to fill the niche, or international companies that can leverage userbases and investments 10 times larger, will push their way in, and starve the niche company out. Local dating apps eat each other, and then they are all eaten by Tinder.

Sometimes great, interesting, truly useful products will fail because, while they don’t have a product problem, they do have a business problem. They don’t have a way of growing and sustaining themselves against shifts in the market. And a company like that can never expect to be successful on a large scale, or for a long time.