Your Ideas are Worthless. You Should be Glad.

Yesterday we received an email that I can only describe as an “hysterical screed” from a disappointed startup founder who felt that his ideas had been “stolen” by the likes of Y-Combinator some years ago. The email included links to an elaborate set of documentation including YouTube videos that compared two products that sort of, kind of do similar things.

Note, neither the message nor the documentation ever contended that any actual intellectual property, such as code or wireframes, had been stolen. Only the ideas behind them.

What was more arresting was the content of the email, which verged into conspiracy theorism and fantasy.

We get our fair share of weird mail. Investors seem to attract people who combine sad desperation with megalomania. Some just want money. Still when Cedric sent me this email saying: “Maybe a blog post?” I responded: “Hell yes.”

I am not posting this to defend the good name of startup accelerators worldwide, nor to defend StartupYard against such an accusation. I’m also not posting it to ridicule this person, because I am sure their problems are deeper than professional disappointment.

Rather I’m hoping to show startup founders how insidious and destructive the concept of “Idea Ownership,” really is, and why they ought to think very hard before making accusations of IP theft. Again, not because these accusations are particularly damaging to those who are accused, but because they are quite damaging to those who make the accusations, and to the many people out there who have great ideas to share.

You’ve Got an Idea? That’s Nice Dear.

The general gist of the supposed conspiracy was summed up in a few bullet points I will paraphrase (though I won’t give free publicity to the author):

Step 1: Accelerators Collect Startup Ideas (via F6s)

Step 2: We “Steal those Ideas” and Give Them to “Our” Startups

Step 3: We Exit Companies 5 Years Later for $300m

Please understand, I am not exaggerating. It was taken as a given that finding the best ideas out of thousands of applications would lead to multi-hundred million dollar exits.

If only that were the case! How easy life would be for accelerators like StartupYard. Not to mention those lucky startups we would give the stolen ideas to.

But sadly no, it just does not work that way. Your ideas are pretty much worthless. Let me explain why that is:

-

Your Ideas Aren’t New, and We Don’t Care

The central plank of this theory is that investors and VCs are out digging through your garbage and listening to your phone calls trying to steal your ideas.

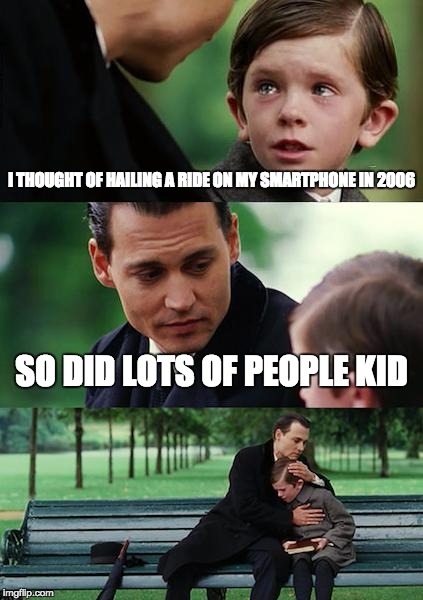

We’re not. You know why? Because we’ve heard them already. Yes, even that one. A typical VC is pitched a couple of hundred ideas a year. I see around 400-500 a year. Every year. It gets so that when I hear a pitch these days, I sometimes struggle to remember whether I have already met the founder who is pitching, because I know about the idea already.

What was funny to me about this particular email was that the idea the author purported to own was not only not a new idea, it was a problem already being solved by existing enterprise software. The pitch was for turning existing functionalities into an SME level product. That’s what we call “an execution play,” in investor lingo. It means the idea is the market, not the product.

You should know this if you’ve ever been to a pitching event with a Q/A. There’s always a smarty-pants judge who points out he’s heard every idea before. Most of them have, it’s just that lazy judges say that instead of something more useful. We’ve all heard the ideas before. There’s nothing new under the sun.

That’s ok because we don’t care much about ideas. We care about finding big problems to solve, because that is going to determine how successful your company is. The thing about big problems is that everyone knows about them. If they didn’t know about them, they wouldn’t be problems to begin with.

So our biggest problems with picking startups is finding the right team to solve that problem, and doing it at the right time.

Just think about this logically for a minute: you have an idea, and it’s a pretty good one. Genius in fact. What industry is it in? How big of a problem does it address? How many people work in that industry? How many people are customers or users of the products of that industry?

Even if we’ve never heard an idea before, it usually takes about 30 seconds of googling to figure out it isn’t a new idea. Even if we can’t figure that out, one of our alumni or mentors can, and frequently do. The question is not whether an idea is new, but whether the problem being solved is real.

The bigger the problem you’re solving is, the higher the likelihood that somebody, somewhere (and more likely many people, everywhere), have had the same exact thought. Their description of it might be different, and their way of fixing it might be different, but the idea is effectively the same.

2. Ideas are Easy to Copy. Vision cannot be copied.

We choose startups based on their vision, and how that vision makes sense for that team, that technology, and the problem they want to solve. It is mostly about people.

To someone not familiar with our thinking, it might look like we hear ideas, then “give them” to our startups. But, thats pretty misleading. It would be like accusing a filmmaker of watching other films, or being inspired by literature. Ideas are wonderful and sometimes very clever. They are just never really entirely new. If they were, they wouldn’t make sense when you heard them.

Of course the iPhone would have been a truly new idea before the invention of electronics. But then, nobody ever had any reason to imagine such a thing before the discovery of electricity, let alone computing and the million other nested inventions in a smartphone. Inventions are always a blend of established knowledge with new approaches.

This popular phenomenon of “idea theft” is more pronounced today in the tech industry than in almost any other- and it’s particularly true in products that rely on a simple central value proposition that is easy to copy. Many products can “do the same thing,” but very few can do it in just the right way.

Look at Facebook, and the endless accusations of their “stealing,” the Stories idea from Snapchat. It’s true that Facebook recognized an opportunity when it presented itself, but the idea of using media to create a narrative was invented in the past few years is ludicrous. Do we accuse Uber of stealing the idea of a livery service?

One of my favorite ever blog posts about this topic is from the creator of the game 3s. When I first read this piece when it was published, I was a fan of their copycat competitor, 2048. Since then, I’ve adopted 3s and actually played it on a near-daily basis for the past 3+ years. Today I understand the piece very differently. What I saw then as mostly whining about competition, today I see as a powerful argument in favor of vision:

“We wanted players to be able to play Threes over many months, if not years (…)The branching of all these ideas can happen so fast nowadays that it seems tiny games like Threes are destined to be lost in the underbrush of copycats, me-toos and iterators. This fast, speed-up of technological and creative advances is the lay of the land here. That’s life! That’s how we get to where we’re going. Standing on each others shoulders.

We want to celebrate iteration on our ideas and ideas in general. It’s great. 2048 is a simpler, easier form of Threes that is worth investigation, but piling on top of us right when the majority of Threes players haven’t had time to understand all we’ve done with our game’s system and why we took 14 months to make it, well… that makes us sad.”

What this really is, is a startup founder talking about how simple his idea was, and how important his dedication to his craft was to the delivery of a special product. He was absolutely right to point out that comparisons between his product and the copycats were unjust, and would eventually be judged premature.

He may not have ended up with the most popular game, but he did end up with the best game, and customers paid for that game, not for the copycats (which were free). They “lost” in terms of being a market leader, but they succeeded in their vision for their users and product.

When you actually stop to think about it, it’s hard to name a lot of first movers in tech who managed to dominate their industries, or even survived. As CBinsights has pointed out using data supplied by failed startups themselves, “late to market” doesn’t even qualify in the top 20 reasons for failure.

-

First to Market Isn’t a Predictor of Success

Shockingly, being first on the market is not a powerful predictor of success. In fact, study has shown that it may be associated with a higher risk of failure. MIT Sloan Management Review noted over 20 years ago that claims of first-mover advantage among successful businesses across a broad base of industries was caused by an effect known as “Survivorship Bias.”

Survivorship Bias, a form of selection bias, occurs when we attempt to judge the relevant qualities of a group, such as a group of startups, after they have become successful, while ignoring the qualities of those who don’t make it. This can lead us to misjudge the importance of some qualities in survival, because we are not looking at all the data.

The logical error is easy to spot when you know how. If I told you that a study of billionaires shows that 75% of them wear white shirts, but only 25% wear other colors, you could conclude that having a white shirt improves your own odds of success. But you would likely be in error. The population as a whole might be 90% white shirts, meaning that in fact another color is even more correlated with success when looking at all the data.

Think about that the next time you dress a certain way because Steve Jobs did. That would be aggressively missing the point.

Survivorship bias arises when we don’t have good data on failures, obviously because they have failed. However, there are ways of determining that survivorship bias is at work. For example, the inconvenient truth that the failure rate for Silicon Valley based startups is actually *higher* than in many other regions. As the Guardian suggests in the above article, this is precisely because so many successful companies are based there. The local standards for success are higher, so failure rates rise.

Does that mean you should or shouldn’t move to Silicon Valley? I don’t know. I know it does mean that moving to Silicon Valley is not guaranteed to help you.

Want even more proof of why first to market is overrated? Of the top 10 startups according to StartupRanking.com, not a single one of them was first to market. Some, like Slack, were not even the first multi-billion dollar companies in their own category. Booking.com offered private flat rentals in the 90s, a decade before Airbnb, and Couchsurfing was founded in 2003, a full 5 years before.

4. Most Ideas Don’t Come from Startups Anyway

A dark and terrible secret of the tech industry -just kidding, it’s obvious- is that most of the ideas that end up getting made don’t come from the founders themselves anyway. The core idea is there, but the final product with market fit is usually a distant cousin of the prototype- the work of many minds.

Where do most actionable ideas come from? Users, customers, advisors, investors, partners, friends, family, and hatemail. I’m only sort of kidding on that last one. The point is that startup founders generally start with wanting to solve a somewhat unclear problem in a somewhat unclear way. They attend accelerators and get early users, investors, and corporate partners on-board to help them make the problem and the solution more clear and actionable.

The really successful founders are not idea machines, they are execution machines. They know how to listen, recognize a good idea when they hear one, make it work, observe the results, and adapt further. There is great creativity and invention in this process, but it is not about ideas, it is about empathy, passion, and skill.

You Should be Glad Ideas Are Worthless

Now that I’ve ruined your beautiful vision of the perfect idea that will make you rich, I will give you a moment to thank me.

You should be happy after all: now you can get on to the stuff that really matters, like building a company you can be proud of, that provides something your customers really value.

Here’s another reason you should be celebrating: you can work on anything you want to. Somebody else already tried it? Not like you will. The problem is already solved by somebody else? I bet some of their customers aren’t happy.

Oh and nobody can credibly accuse you of “stealing their idea,” since ideas are not automatically intellectual property. Intellectual property is the work product of an idea, not the idea itself. Copyright applies to words and images and code. Patents require you to actually design an invention and describe how it works in detail; even then, it’s not automatic. A patent is for the bread slicer, not the sliced bread.

Call the lawyers. We’ve got a live one.

If someone has already done what you want to do, thank God somebody has already proven you can make money in this field- that makes your job a lot easier. Or thank goodness somebody else tried this and failed. Now you know not to make those same mistakes. See? Now that ideas don’t matter, the world is truly your oyster. Go forth and start up.