SY Alum Turtle Rover: “You Can Speed Up, But You Can’t Skip Anything”

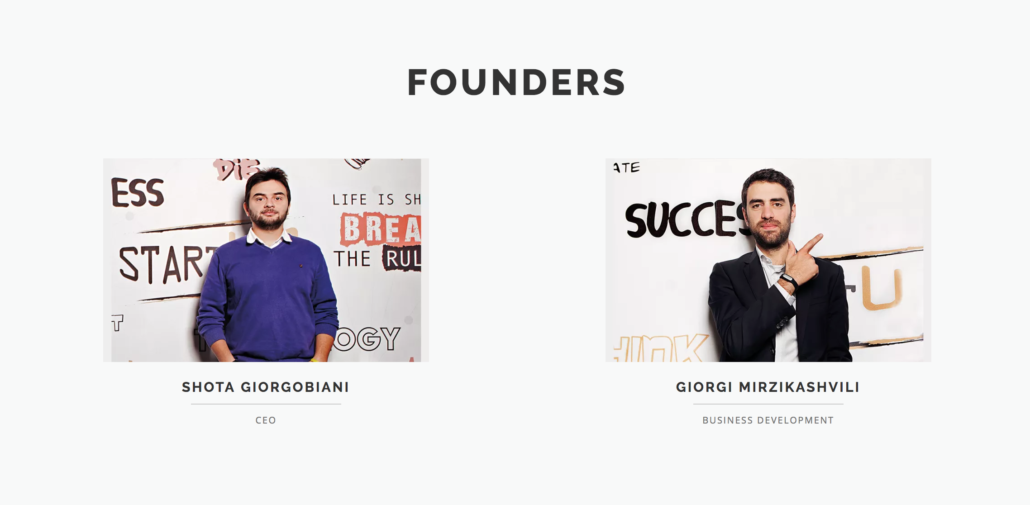

SThis week as part of our ongoing series of talks with alumni, I sat down with Szymon Dwonzczyk, CEO at Turtle Rover to talk about his company’s transition from a pre-product academic startup, to a Kickstarter funded project, and eventually a post-acceleration StartupYard company.

Szymon focused on providing some insights into running a hardware focused tech startup, and shared his experiences with crowdfunding, venture capital negotiations, and his philosophy of customer-led product development. In particular, Szymon talked about the process of a small company building its confidence and sense of self through exposure to customers, advisors, and investors.

Here’s what he had to say:

Hi Szymon, as you know, this series is about giving advice to our current members and your fellow alumni. What do you think you’ve learned in the past year that you didn’t know before?

It can sound a bit formulaic, actually, but I think since joining StartupYard, I have realized that self-confidence is probably the most important quality that a founder can have. You have to be focused on building up your self-confidence and self-esteem. Without that, you can’t get anywhere.

So why are you so much more self-confident today?

I think in a year the Turtle team have grown enormously in our confidence about our ideas. We are able to see more clearly that the best way forward is the way that we believe in most. I think today I am much better able to say that I can adapt and learn how to grow the company in a way that makes sense for us.

I would like to point to three ways that I think anyone can build that kind of confidence, and explain why they have been important to me.

Number one, being forced to speak and perform in public. I can say I was not afraid of speaking in public before joining StartupYard. However I always had issues getting my point across to people. It was not hard for me to speak to people, but hard for me to express how I felt, and not only what I thought. The mentoring process and prepping for the Demo Day is an emotional experience, and it made me much more open.

I can say this changed for me a lot, leading up to, and after our Demo Day. It turned out that I really enjoyed the experience of refining our company’s story, and getting the pitch exactly right. I found I enjoyed expressing my feelings more. I liked seeing in people’s faces that they understood and were suddenly excited about this crazy robotics guy from Poland. I was excited too.

Szymon presents Turtle Rover at StartupYard Demo Day 9

If people can see the same thing you can see, this is enormously good for your self-image. You can be sure you’re doing something valuable.

Number two, I think is talking to a lot of people who may disagree with you. Talking to people often, and early on in your thought process, is really important as well. I realized I think that because of the mentoring process, we probably made as much progress in product development in 1 month as we had done in the previous year.

That is not even because mentors gave us new ideas. Just because they confirmed many things that we initially believed, and helped us to dismiss other things that we were not sure about. Mentoring strengthens your ability to fight for what is naturally right for you. You lose this fear of making mistakes and going against your instincts, because everything you believe has been tested with over 100 experienced people.

Talking to people early and often about your ideas helps you to see them more clearly and take action. Talk to a lot of people.

Lastly, I think being forced to think more about our competitors has helped us to understand ourselves, and to value what we do even more. As you say yourself Lloyd, your competitor can be anything your customer is doing. Your customer themselves can be your competitor, especially in our case because we provide a product that is targeted at makers and robotics people.

I think we saw our competition as always these companies we wanted to be like. Like Boston Dynamics for example, or even companies like Tesla- if they started to make autonomous rovers, we would be screwed!

That’s the way we were thinking, but we saw increasingly that our true competition is not as strong or as well-defined. We compete with behaviors and ways of thinking; what is possible, and what is not possible. If we can convince you that it is possible to create your own robot, with a never-before-seen set of abilities, from scratch, then we have won against our competition in that way. If you decide to build on top of our platform, then it’s a success for us.

You mentioned that your understanding of competition changed quite a bit. How did your understanding of your product change in the last year?

:laughs: It’s funny because the product, just looking at it, changed very little. It is still Turtle Rover. It looks the same, essentially. What changed was our understanding of the product and who it is for.

When we first were making Turtle, of course it was just for us. We are robotics engineers. Then we thought as you always do, that it must be for people who are like us. This assumption we held for way, way too long without any real feedback.

Then two things happened: first we successfully ran a kickstarter campaign, and then we were accepted at StartupYard. In that space of time, we started to see that our customers were not like us, actually. They were photographers, teachers, engineers, makers. All kinds of different people actually.

It was this sudden realization: “oh… this product isn’t a robot to you, it’s a way to do what you really wanted to do.” Maybe it sounds obvious, but it wasn’t.

Then we were suddenly hearing from a lot of mentors and investors, and again they were telling us, “there’s something here for these people, there’s something for them.” There are suddenly many more possibilities.

What I learned, most importantly, is to make assumptions and test those assumptions more quickly, and more consistently. We had many ideas over the years like: “you can use Turtle to do X,” but we would just think about it. Then actually working with live customers and mentors, we decided “ok, if someone says we should do X, let’s try it.” We actually saw them how complicated it might be to sell that idea, or to make it work. Or we can see how easy and natural the idea actually is.

I think this is something I have learned: do less planning, and do more doing, in general. If you have ideas, get feedback, and get that idea to the MVP stage as fast as you can to get the right kind of feedback from the right people.

So basically, you’re following the Tesla approach to product development…

Yes, I think that’s fair. We are not doing anything at scale like Tesla, so we don’t face the downsides of this approach.

There is a big advantage in shipping a product to the right people even before it is ready. For example, we had a case recently where we were delaying shipping a bunch of rovers to customers because of an issue with Android/iOS compatibility. FInally I just said: “screw it guys, ship it and tell the customers about the issue.” And we shipped it, and you know what? The issue was with our own systems, not with the product. The rovers we shipped worked fine for the customers.

There are many cases like this, where you allow something internally to become a big deal, and actually to customers it maybe isn’t a big deal. Particularly since we have these early adopters, and we are still in the test phases, we have learned you have to have more faith in these people to help you and to solve problems themselves.

The result for us is that many times our customers show us how to do things because we have given them that opportunity. One customer ordered the rover for a museum exhibit, for example, to demonstrate the technology. I found I was almost trying to talk him out of this idea, because I saw that there were going to be some connectivity issues that would be hard to solve. I wanted to help him set this up so it would not fail.

I needn’t have worried because the museum guy is also a tech guy, and he anticipated these issues, and had his own solutions. Actually his network solution was better than ours, so it’s something we benefit from. I had to trust him to do that, and trust that we were sending him something that would not be embarrassing to us when he tried to use it.

Do you think this strategy is something startups should do more, generally?

Yes. Totally. I didn’t realize to what extent early stage companies really ignore their customer feedback and don’t trust their customers to understand them as a small company, and accept errors.

You end up basically fearing the power users of your products because they are the ones who will cause the most “problems” for you in customer support etc. That’s wrong, because these people help to build your knowledge base, and discover a lot of problems before anyone else does. You can use them to make you stronger.

You see so often these small startups that try to act as if they are big corporations. That is a shame to me, because they are missing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to have a different relationship with customers. Later on this is not going to be possible so today, we really choose to open up and be transparent with our users as much as possible.

Do you have any concrete advice for a hardware startup in a similar position to Turtle?

Yes. If you are thinking about crowdfunding, such as Kickstarter, then do your research on the most common failures. Don’t believe every catchy bulletpointed list of “tips & tricks.” The people you want on Kickstarter are the ones supporting you, not just the product.

Most importantly: do not outsource your development from the beginning. That is my view, particularly if you are crowdfunding, you will be tempted if the campaign is successful to outsource more and more, and depend on more and more others. This is where most kickstarters tend to fail: they get a lot of traction, and then they try to outsource too much.

If you outsource too much, you don’t gain enough experience. You get the job done, but it doesn’t help you to streamline or improve your processes. It doesn’t help you understand what you are capable of on your own.

We intentionally kept our campaign limited in size, and only accepted true first adopters. This is because if you fail to deliver on one project on Kickstarter, basically you can never do it again. That failure will follow you everywhere. People will think you’re a scammer, and you can’t even prove them wrong if you’ve outsourced the failure, and don’t have anything to show for it. That’s why we were very conservative in our goal, and we are still today working on completing it. If we go back to crowdfunding, we have to have that good history of delivering.

The other thing I want to say is that if you are talking with VC investors, you really need to understand the Venture Capital approach to business. You have to decide if that is the right way for your business to grow. I am open about not being convinced of this today. I believe it may be better for us as a company not to raise money. Startup founders need to be open to this possibility, that it can be better to leave money on the table.

That’s just my feeling. I’m a very Slavic guy, and VC culture is very American I guess. I see VC money as a way to scale, not a way to survive. If I had something I was absolutely sure would scale tomorrow with more money, ok, VC is a good idea. However if you are thinking VC money will save your business or help you to develop a product that is not proven yet… well I think you will have a harder time.

To me, it is a lot easier to build a business model not counting on the investment, and simulate where can you be in 2, 3, 5 years from now. Then use the VC money to speed that up – instead of 5 yrs of development, be there in 2. But anyway, don’t underestimate the power of time – you’ll always need time to learn all the processes in your company, learn how to run the team and prepare the product – it’s not about money, not about finding the right mentors, it’s about gaining the experience that most probably you don’t have – and it needs time, and time only.

At the end of the day, you can speed things up but you can’t skip anything.