Our Top 3 Reasons Startups Fail: Featuring CB Insights Data

This is going to be a post about what makes startups fail. But first of all, if you don’t regularly read CBinsights and receive their newsletters, then stop reading this post and go sign up. There’s a reason most newsletters don’t have 400,000 weekly readers.

If you do, then you may have seen a bit of content that CB insights has been updating consistently since 2014: The Top 20 Reasons Startups Fail. This is a list compiled from a sample of over 100 “Post-mortems,” written by founders and employees of high profile startups that failed.

The list is ranked by the number of times a specific reason for failure is cited – each post-mortem contains some combination of these reasons:

StartupYard’s Top 3 Startups Fail, and How to Avoid Them

We won’t detract from this piece by hashing out every reason startups might fail. Instead, we’re going to focus on 3 of these reasons, and how to avoid letting them kill your startup before it starts.

Some of these reasons also explain why we choose not to work with some startups that apply to our program. If you’re thinking about applying to an accelerator or talking to early-stage investors, then these are important questions to ask about yourself and your business.

-

Ignoring Customers

Oh boy. This is a big one. For me, this is the big one. The mistake that kills a startup dead like a beautiful rose in a dry vase. Ignoring your customers, refusing to think about them and to be driven by their needs, is the kiss of death.

It all starts so innocently: a humble coder working nights and weekends on a passion project. That’s the way a startup should start, but the nature of a startup is to grow – not just in size but in mentality.

Every startup investor and mentor has had this conversation:

Mentor: who are your customers.

Founder: Well we are our own customers.

Mentor: Yeah… but who is going to be your customer? What do they need?

Founder: They need our product.

Mentor: Why?

Founder: Because it’s awesome. They’ll love it.

Mentor: Yeah but… why your product? What not a competitor?

Founder: Because we are newer/smarter/cheaper/better UX, etc.

Mentor: How do you know that’s what they’re looking for?

Founder: Because we are the customer.

Points to you if you can spot the tautology in this reasoning. I strongly agree that a problem you are passionate about solving has to be one that affects you. In that sense, you should be your first user, you just need to remember that the customer is somebody you can also learn from.

A good way of remembering that is this: you didn’t buy your product. You built it. Your customer will buy it. Even if you both have the same problem, you are not the same person.

Again, it’s essential to create something you would use yourself. It just isn’t enough. Great products involve a deep insight into the motivations of customers; even when that insight is a very simple one, or an instinctual one, it does not come about by chance, but by observation and curiosity about people.

Thinking About Your Customers:

How to avoid this one? It happens that we’ve shared a lot of content on this theme. Positioning for Startups, Bulding a Killer Customer Persona, and The “We” Problem, are good places to start.

In short, it comes down to having a process. Here is one you can try:

- Develop customer focused product/messaging frameworks (aka: Positioning)

- Make educated guesses about your customers in that framework (aka: Personas)

- Test these frameworks with real people and an early product or mockup.

- Redevelop your product and business strategy based on what you’ve learned

There’s not one way to do this, but there are plenty of ways to do it poorly. Not having a clear idea of what you know and don’t know about customers is a mistake that’s easy to avoid. Paul Graham put it this way in one seminal blog post:

“When designing for other people you have to be empirical. You can no longer guess what will work; you have to find users and measure their responses.” -Paul Graham

2. Lacking Passion

“You need passion,” we are so often told. Less often are we told what that means.

I think this is why some founders confuse “having passion,” with “being energetic,” or “assertive,” or “dominant.” These are not the same things.

Passion comes from within – it’s not a performance art; it guides what you say but also how you think, what you are willing to do, and what setbacks you are willing to accept. In short, it’s not about how you behave, but about who you really are.

Everyone has some passion. It’s the thing that keeps you up at night, and bothers you throughout the day. A little voice in your head telling you something needs to be done.

Understanding their own passion is pretty hard for some people. We’ve seen that a lot. We spend a lot of time with founders trying to find out what gets them really engaged and excited about their work. What gets you out of bed in the morning is what’s most important in your work.

One of the first thing we ask applicants to StartupYard is: “Why are you doing this?” The answer says a lot about your passion.

A lack of passion is easy to spot, if you know what to look for. Here’s an overview of the qualities that typically tell us a founder lacks the passion they need to move forward:

- Risk Avoidance: Founders who are unwilling to take risks, such as leaving a job, moving to a new place, or bringing on a co-founder.

- Waiting: The founder who bases their decisions on the actions of others; who waits rather than acts with intention. “I will leave my job if you give me funding.” “I will decide what to do based on what investors say.”

- Focused on Money/Valuation: Some founders who are overly focused on “getting the best deal,” do so because they value control and personal gain more than achieving their stated goals.

- Motivated by Opportunity: I sometimes say: “don’t pitch me an opportunity, pitch me a company.” A founder who talks about getting a piece of a huge market might not be doing what they do out of a love for the work.

- “Win At All Costs” Attitude: In my opinion, this happens when founders confuse passion for ambition. Ambition isn’t a bad thing, but it isn’t passion for what you do- it’s a passion for winning. Your passion for helping customers has to ultimately outweigh your personal ambitions, or else you won’t make decisions based on what’s right for them (and thus your business), but rather what fulfills your ambition.

Seeking your Passion: How do you know you’re doing things for the right reasons?

In my view, this is a simpler question than people often make it. We are taught from an early age that we should emulate those who are successful, but education systems often don’t help us to really understand why successful people are special to begin with: because they have a passion for what they do.

For all the tactics, tricks, and habits of the rich and famous, passion underlies everything. People succeed when they do what they are good at, enjoy it, and are willing to work harder at it than anyone else.

Just consider the following questions if you want to get in touch with your true passion:

- If I were rich, would I stop doing this?

- Are there better uses of my talent?

- Am I waiting to enjoy what I am doing?

- Am I doing this in order to be able to do something else?

If your answer to any of these is “yes,” then you ought to think hard about what you’re doing. You haven’t yet found your passion.

3. Missing Product-Market Fit (PMF)

“When a great team meets a lousy market, market wins. When a lousy team meets a great market, market wins. When a great team meets a great market, something special happens.” – Andy Rachleff, CEO, Wealthfront

Even if you’re doing something you really care about and you’re doing it for customers you understand really well, you can still fail to make the right product for the right market.

Andreessen-Horowitzs has a fascinating post on product market fit, in which they quote Andy Rachleff who developed the PMF framework, starting with what he calls a “Value Hypothesis:”

“A value hypothesis identifies the features you need to build, the audience that’s likely to care, and the business model required to entice a customer to buy your product. “

There are two sides to the PMF equation. Market, and Product. Missing PMF means failing to address a specific market with exactly the right product, at the right price.

Right Market

Andreessen-Horowitz heavily emphasizes finding the right market first, which is another way of saying that you must identify the right problem to solve. If you pick the wrong market, you can end up building a product that people love, but won’t pay for.

This happens more than you’d suspect: plenty of popular products have never gained good PMF. Even mega-popular products like Twitter can teeter on the edge of failure, and take over a decade to achieve PMF (which Twitter seemed to do only in 2017, with their advertising business and focus on media and news).

Other orphans of bad PMF are products like Tumblr, Vine, Soundcloud, and BetaMax tapes. Each of these has either failed, or is now on life-support. The latter example of BetaMax is included in this extensive list from Business Insider. In fact, virtually all the products in this list failed because of lack of PMF. Not because the products were bad, but because the business model didn’t work: the market didn’t sustain them.

The Right Product

“First to market seldom matters. Rather, first to product/market fit is almost always the long-term winner.” – Andy Rachleff

So picking a problem you can solve, for a market that wants a solution critical. Still, you can manage this and still fail. The product that solves that problem also has to appeal to the customer enough for them to use it.

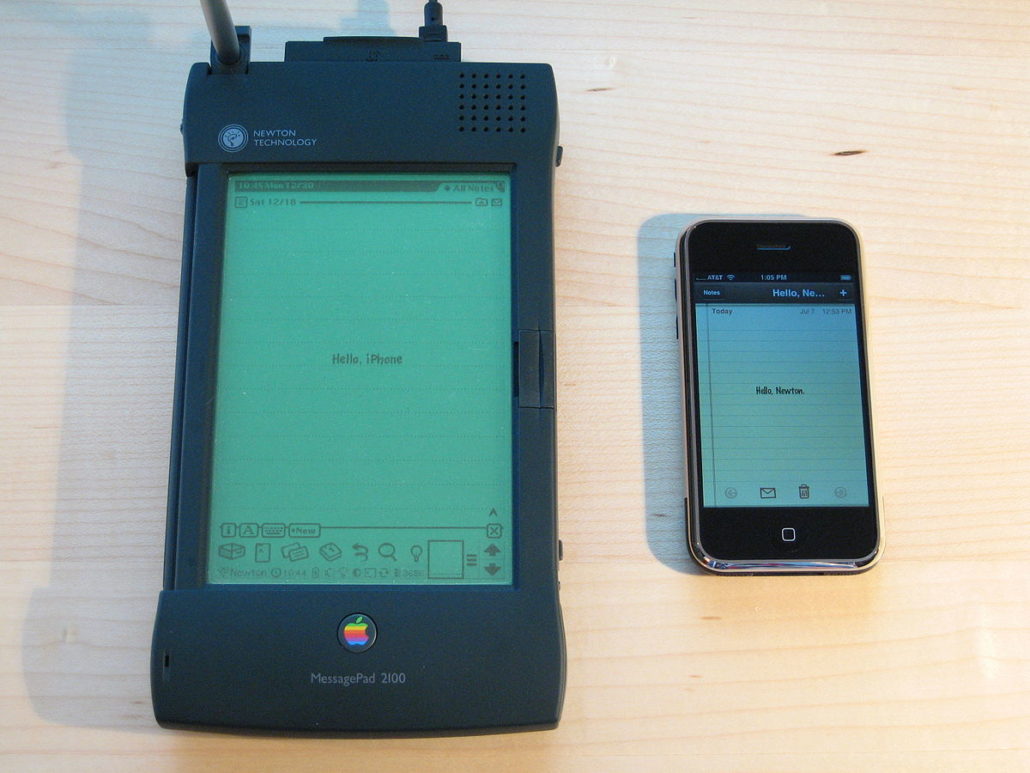

A great example of this also comes from BI’s list: The Apple Newton line, which lived from 1993 to 1997, and which Wired later called a “Prophetic Failure.” What most people don’t know about the Apple Newton line was that they very accurately predicted three distinct product categories, which would emerge in the following 15 years: the smartphone, the tablet computer, and the modern consumer laptop.

In many ways, looking at a Newton from 1995 feels like looking at a cyberpunk version of a modern device, made to look like a 90’s product.

The Newton failed in three categories that would go on to be the fastest growing market categories in history for computing, but still failed because the technology wasn’t ready. As the project lead Steve Capps said later: ““We were just way ahead of the technology. We barely got it functioning by ’93 when we started shipping it.”

The series failed at least partly because the market was not ready for such devices, but also because of its infamously bad character recognition feature. Even though later editions of the devices improved on the original, it was too late for Apple, which would spend the next 20 years rebuilding itself and slowly reintroducing all of these concepts in the form of the iPhone, iPad, and Macbook.

Testing the Value Hypothesis:

Like listening to your customers, PMF is all about trial and error. Make certain assumptions, test them with a minimum viable product, make more assumptions, and test them. The clearest milestones for PMF come from customer feedback about the Value Hypothesis.

You can begin to test this hypothesis right away, even with just an idea- with no product to show. It’s pretty simple: if you get confusion, lack of enthusiasm, or even hostility, either it’s the wrong product or the wrong market. Find out what the person you are talking to does want, and also look for others who do want the product you’re pitching. Chances are the answer is somewhere in the middle.

This is a bit like fishing. Either change the location or change the bait. It just takes time and consistency. Fish long enough, and you can get lucky.

For example, I was attending a tech conference a few months ago, when I got the chance to meet the former Senior Vice-President of a major electronics company. He mentioned that he helps early stage hardware companies find PMF, and I mentioned we had just such a company seeking PMF: Steel Mountain.

He asked me what the company did, so I gave him the 90 second water-cooler pitch. Within a few moments he was nodding. When I got into some of the features, he was saying: “yes… yes.” When I finished, he exclaimed: “I can’t believe no one has done this! When can I buy one?”

This, I must repeat, was the former Senior VP of a major electronics company, whose products you probably own. Nobody had ever pitched him this particular idea in just the right way before. That is a powerful indication of PMF. You don’t have to convince the customer they need the product, because they know they need it.

Still I may lack some important information. Is this customer representative of a distinct market segment? Is the business model workable for the target market? Does the product work the way they want and expect?

You still have to explore all those details, but enthusiasm for the product’s core value proposition is a great milestone. It was then the Steel Mountain team’s job to continue testing the product with the same customer and others like him.