6 Things Our Startups Learned in 2016

As our 9 startups leave us, and begin the real journey of growing into their own companies with their own bright futures, we thought it would be valuable to look back on some of the things that many of them learned in the past 3 months. I asked our teams: “In what way has your thinking changed in the last 3 months, and why? What lesson did you learn that you couldn’t have learned any other way? Some of the answers are collected below. Here are 6 things our startups learned in 2016:

The Customer is Not Always Right, and a Customer is not a Client

Many of our startup teams have experience in business, but many have also spent the earlier part of their careers working on technology projects as consultants, engineers, or project managers. That’s vital experience for any startup founder, but experience is a double edged sword. We as often as not encounter situations where our founders’ experience in business works against their judgement as startup founders.

As a consultant, or a project manager, one works at the behest of a client who understands what they are paying for, and why. Their needs have already been laid out in clear terms, and the solution, including the work needed to solve it, has in a sense been sold even before the work begins. Because projects have clearly established parameters for success, a project manager or consultant has something to work towards, and clear feedback on the work already done.

But it’s just different with startups. Startups typically have customers, not clients. They produce something new, and find people (customers) who understand and want the value that product provides. A client asks for something, and it is delivered. A customer doesn’t know what he or she wants yet, but can be convinced that they need what the startup provides.

Most of the time, startups are working on concepts and products that customers not only didn’t ask for, but may not even understand. Much of the early work of a startup is to figure out what a product actually is, and how that can be communicated to a potential customer. Instead of working toward a common goal, a startup has to do the work, and then convince a customer that what they’ve made is worth buying or investing in further.

Because so many founders are used to tailoring their work to the needs of a client, they can start to adopt the objections of the potential customer as their own objections. Every week, we hear some variation of the result

SY Team: “What about x feature you were working on?”

Founders: “we talked to a potential customer, and they said they didn’t want that.”

SY Team: “How did you try to convince them that it would be valuable for them?”

Founders: “We were really just listening.”

Just listening is what a consultant does in the first meeting. But a startup is pitching something new; something probably unexpected, and something that customer doesn’t yet know that they want. First meetings with customers have to sound out the idea, in order to see if it is being communicated properly. If the customer doesn’t like the idea, then it may be time to talk to others, before changing the product.

We also hear a variation of that story, where the startup adopts the ideas of its first potential clients, instead of selling its own vision:

Sy Team: “Why are you doing x feature now? Why focus on that now?”

Founders: “Because a potential customer said they wanted that.”

Sy Team: “Did they agree to buy from you if you had it?”

Founders: “Well… not yet. But we think they will.”

This is of course an ideal circumstance of a customer, They now have an expert team developing a dream product for them, and best of all, they’re doing it for free. If the customer doesn’t like the result, they lose nothing in the exchange; while the startup has invested time and resources into something it may not be able to sell at all.

A Pilot is Not Just a Pilot

We happened to have quite a few companies in this cohort that struck deals for piloting their products with prospect customers.

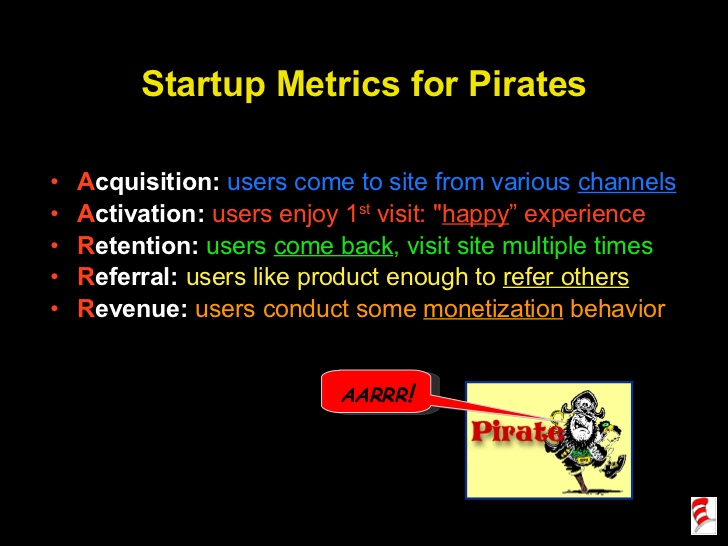

That’s great progress, and it opens the door to future business. But it’s not the customer’s job to push the sale, or to evaluate the pilot by themselves. A startup that runs a pilot without specific goals and success metrics is like a car dealership that finishes test drives by dropping the customer off at home.

Maybe the customer will come back after the pilot, maybe not. But you’ve failed to do your part in the transaction if the pilot you run doesn’t have a clearly defined goal.

If possible, a startup should run a pilot that can easily become a long term business relationship. There should be a conversation before the pilot begins, that covers these questions: “What will define a successful pilot?” “Who will determining that a pilot is a success?” “What will be the next step after a successful pilot?”

Ideally, a pilot doesn’t end, it just becomes a business relationship. If a customer wants to “evaluate” a pilot after it concludes, then very convincing evidence needs to be prepared that the pilot actually worked. It should not be a question of expense for the customer, but of opportunity: the pilot should prove that an opportunity exists, and that the customer can’t afford to skip it.

Customers can readily agree to a pilot, if it costs them very little of their time or focus. They can agree to a pilot just to get out of a meeting with a startup- and we’ve seen that happen plenty of times. The startup comes back with the good news that they’ve agreed to a pilot, but when it comes to taking the steps to make that pilot customer a paying customer, no progress has really been made.

Partnerships Should Cost Something

Like the aforementioned pilot, a partnership can be an easy thing to agree to. We’ll put your logo on our website, and you put your logo on ours. That is the extent of a great number of tech company partnerships, and there’s nothing inherently wrong with that. It is good to give customers a sense of who you are connected with in your industry.

However, a partnership in name-only is not as good as a partnership that costs both you, and the partner, something real and tangible. I’ve touched on this in the blog before, but it bears repeating here: you should partner with companies that need something real from you, and which you need something real from in return. Without a mutual interest on the table, a partnership is at best an unnecessary distraction

Play to Your Strengths as a Founder

One of the hardest things about being in an accelerator, from what I’ve observed, is that every mentor has a different view of the kind of company you should be. Often though, a mentor’s ideas about your company are as much a mirror of their own desires, as of what kind of company you should really be building.

That kind of feedback is very valuable- it gives you insight into what makes others passionate, but it can’t replace your own passion.

Founders sometimes run into what I have started to call a “passion gap,” between the passions of their advisors, and their own desires. They try to be like the mentors they admire, instead of trying to do what they really love doing. This can lead a founder to feeling frustrated and worthless, when he or she isn’t as good at what they’re trying to do, as at what they really love doing.

What we’ve learned over the last few years, is that you need to play to your strengths. You just have to do what you love- and you can’t make yourself love whatever you are doing. It can be a magical thing to see a founder find the sweet spot between what they love to do, and what makes sense from a business perspective. That balance can be very hard to find, and it may only come up after many brainstorming sessions, and a great deal of work that doesn’t go anywhere.

In one case in recent memory, a team in our program went from a pervasive sense of failure and disappointment, to make increasingly positive steps- and it all started when they took themselves off the hook for what they thought others expected of them. Once they started doing what they were actually good at, things turned around in a hurry.

How to Ask For Help

The startup life attracts a certain type of personality. You have to be a little crazy to want to start a company, with no guarantees that there is a real market for your product, or investors actually interested in funding it. We look for the type of person who is comfortable dealing with uncertainty, rejection, and oftentimes, failure.

We stepped down from being managers lecturing and teaching rookies in our business workshops to becoming students and listening what others had to say. Others that we by all means respected. So the chance to realize and re-discover humility or meekness was not only useful in the process of mentoring but also further down the road as this attitude helped us see things we might have not seen in our previous business, or wouldn’t have seen without Startupyard.

What that means, is that we attract founders who don’t take “no” for an answer. That’s a good thing generally, but it also presents problems. Knowing when one should listen to negative feedback makes the difference between a naive founder, and one who is able to adapt and thrive despite problems. Drive and independence of thought can as well lead a founder to ignore important feedback, as it can cause him or her to persevere when others would quit.

Listening well and actually getting the help you need often comes down to what questions you’re asking. To me, there are essentially 3 types of questions that founders ask most: “open” questions, “closed” questions, and “save me” questions.

An open question can be: “what type of email marketing service should we use?” That’s fairly straightforward- the founder is just asking for input and options. Nothing amiss here.

Closed questions are productive as well: “do you think this landing page is good?” While it’s a yes or no question, it starts a useful conversation.

Finally, “save me” questions are where some founders run into real problems. “How do you reach out to the press to get good PR?” Or, “what should we do to improve our sales funnel?” Worse still, would be a startup founder asking an investor: “is there any appetite for this kind of investment?”

These are “save me” questions because they aren’t really questions, they are cries for help. The founder is really asking: “what should I be working on?” “What should I do right now?” These questions first fail to instill any confidence, and second, don’t elicit very useful responses. The response will depend almost entirely on the mood of the mentor, and put all the work on their side of the table.

A far better question is an open or closed one, which essentially asks: “Am I doing the right thing?” “Am I missing something?” A mentor or advisor is far better equipped to react rather than to dictate. And when a founder puts the work in ahead of time, shows their thinking, and asks questions that shed light on that thinking, they are much more likely to get substantive and useful feedback.

It’s Not About Dreams, It’s About Vision

“It is not about dreams. It is all about a vision. And StartupYard helped us to find a path, how we can make our vision a reality. So we just need to roll up our sleeves and get busy. There’s a lot of work to do. “

One of our founders told me this week that for them, the realization that the work of a startup is about vision, instead of dreams, was a core part of their experience at StartupYard.

I had never thought about it that way, but I think he was on to something. A lot of founders have dreams, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But dreams don’t necessarily come with a coherent plan for dealing with the reality of any given situation. You may dream of big valuations and great achievements, but without a clear vision for how you will achieve them, they’re just dreams.

Vision, on the other hand, is about having a concrete, realistic set of objectives, and a way of achieving them that makes sense, is aggressive, and can be clearly communicated to investors, advisors, and partners. While we look for startups that have big dreams, we end up pushing them to pursue a clear vision.