2 Mental Tricks That Will Make You a Better Entrepreneur

This week at StartupYard, our current batch of companies has been in the tall weeds trying to finalize their marketing and messaging for our press launch, which went off last week.

The cliché expression for the feeling they are experiencing is “jumping off a cliff and building your wings on the way down.” A version of that quote is often attributed to Reid Hoffman, who uses it to describe entrepreneurship generally. In fact, the quote originated with the science fiction author Ray Bradbury, in a review of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C.

In a way that makes much more sense. The quote describes inventiveness and forced creativity. It can be the realm of the entrepreneur, but it is more generally the realm of anyone creative.

The reason I mention this is that a founder can be both very strong in creativity, and still very unconfident in their ability to creatively communicate with customers. That’s what my job with them is all about.

Creativity and Empathy

This week I’ve done two workshops with our startups. One on “Storytelling,” and the other on “Customer Personas.”

To me these are essentially the same topic. Stories are the way that the human mind invents and creates the future, and how we understand our past. It is about how every “character,” or person undergoes an arc, and how those arcs interact and impact each other. Building personas, in the way I see it, is how we examine our assumptions about people, formulate tests of our insights, and discover ways to empathize with and understand those who use our products.

Here we’re going to talk about some simple mental tools that are going to help you ideate and test your own assumptions about your customers, in order to better serve and sell to those who need your products most. In many ways these will not be unfamiliar concepts, but to the mind of an engineer or a maker, they are often mysterious and elusive in terms of application, particularly when it comes to marketing.

I’ve written a number of posts on this topic, so I encourage you to start with these. Go on, I’ll wait.

…

Double Loop Learning

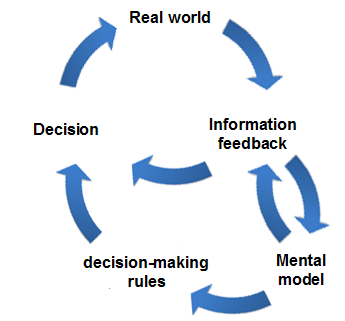

Double loop learning is a basic model for creative and flexible thinking. In essence, it suggests that there are two ways to approach the learning process (such as in product development), a “single loop,” or a “double loop” process.

Here is how they look:

In the Single Loop Thinking:, you begin with assumptions (a mental model), logically leading to a set of rules, which lead to a decision. From there, you adjust your decision based on feedback.

In Double Loop Thinking: You do the single loop, but at the same time, you go back to the initial assumptions and adjust the mental model, which may cause you to adjust the rules, and not just the final decision.

Example of Single Loop: In deciding on buying a car, I imagine the car I want to buy: Color, Type, Make, Model. Using this model, I decide which dealership to go to, and how much I can expect to spend (making rules). Based on this, I decide on a dealership. Now I go to the dealership, and I find out if I can get the deal I want for the car I want. If I can’t find the car, I go to another dealership (information feedback to decision).

Example of Double Loop: I do all of the above. But I also ask myself: should I be trying to buy this type of car? Were my ideas realistic? Based on what I learned from my visit to the dealer, what other cars got my interest, and might be better for me? I adjust my expectations, and make a new decision about the kind of dealer I need.

Why it Works:

Single loop is in fact the way we are taught to learn in school. We are given rules, and told to apply them continuously, looking for the correct decision given the stated rules. Just think of all that math homework you had to do.

That kind of singular repetitive learning works most of the time, particularly when a desired outcome is pre-determined. However, this can also lead people to forget that the initial mental model may be flawed, particularly after gaining real experience with it.

The most typical case in startups, is the startup that makes some early decisions about who the customers were and what they wanted, but never came back to those assumptions, and ends up serving a smaller niche than necessary, because all their later decisions are based on data they’ve gathered so far. The longer a company remains in this “single loop,” the less likely they are to challenge their original assumptions and thus be able to successfully pivot to a new market.

Here is a concrete example using a classic business case many people face even as kids:

Single Loop:

1. I decide to sell lemonade. I choose a location for my lemonade stand and a price for the lemonade, based on my intuition about what people will pay.

2. I observe the sales cycle. How many people visit, and how many people convert to buying a lemonade.

3. I slightly adjust prices and location to optimize my sales.

4. Go to 2.

Double Loop:

- I decide on a location for my lemonade stand and a price for the lemonade based on my intuition.

- I observe the sales cycle.

- I slightly adjust prices and location to optimize my sales.

- I re-examine my initial strategy, and try a new location, or even a new product (maybe ice cream?)

- Go to 2.

The OODA Loop

Ok, maybe running a startup isn’t exactly like flying a combat mission in a $50m fighter jet in the U.S. Airforce. Still, you can learn from the mental training that fighter pilots, spies, and military strategists use on a continuous basis – often minute to minute.

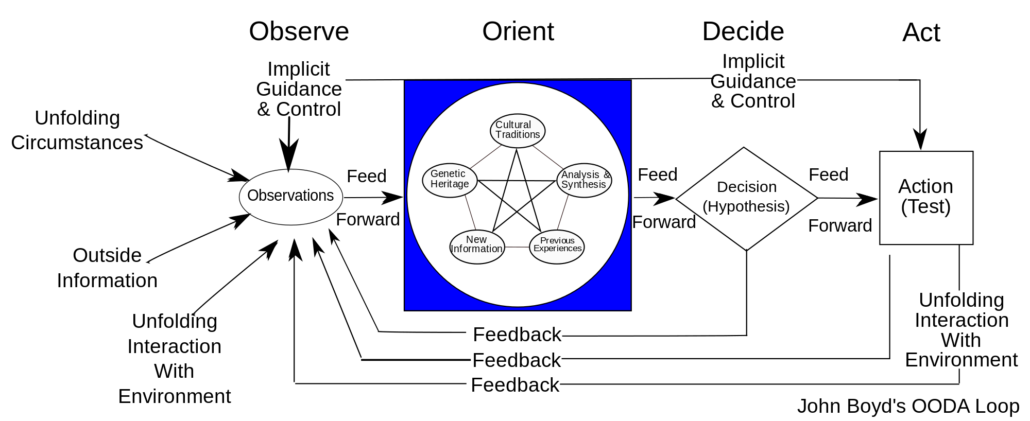

It’s called the “OODA Loop,” for Observe Orient Decide Act, invented by Air Force strategist John Boyd, called by some “the greatest military thinker no one ever heard of.” Here is a very thorough explanation of the general philosophy behind it, written for a popular audience. In as simple terms as possible, the OODA Loop is a mental tool which forces its user to continually adjust their future expectations, based on current realities.

Why it Works:

The OODA loop is a tool for forcing oneself to continually affirm their past decisions using current information, and to drop previous assumptions and goals based on current circumstances. The OODA loop is used as a mental tool to keep you focused on the current moment, and what is happening around you, to avoid sticking to a strategy which is not working, and to continually notice new opportunities.

Boyd’s central thesis has become a core principle of modern warfare, and a frequently used technique in sales training, and even by professional chess players. The core tenet is this: the mental models one holds tend to lose their usefulness in chaotic situations. Therefore, updating our mental models, or “orienting” our expectations can help us to make better decisions for any given situation.

What does that look like practically? I’ll refer to a thought experiment that Boyd himself proposed:

“Imagine that you are on a ski slope with other skiers…that you are in Florida riding in an outboard motorboat, maybe even towing water-skiers. Imagine that you are riding a bicycle on a nice spring day. Imagine that you are a parent taking your son to a department store and that you notice he is fascinated by the toy tractors or tanks with rubber caterpillar treads.”

Now imagine that you pull the skis off but you are still on the ski slope. Imagine also that you remove the outboard motor from the motorboat, and you are no longer in Florida. And from the bicycle you remove the handle-bar and discard the rest of the bike. Finally, you take off the rubber treads from the toy tractor or tanks. This leaves only the following separate pieces: skis, outboard motor, handlebars and rubber treads.”

The thought experiment then asks us to orient to this new situation by putting all the elements together, not in reference to how they were introduced, but rather only focusing on what the elements themselves are, or can be.

You are on a ski slope. You have skis, you have a motor, you have handlebars, and you have rubber treads. What’s going on?

Spoiler: You’re on a snowmobile. That’s what’s happening. Nothing you learned to this point other than those facts matters. To master the OODA loop, you have to be able to clear your mind of these details when they are no longer useful.

The OODA loop focuses on observing the current situation, combining that data with experience and knowledge, and making a decision focused on what is happening right now.

Actually we are quite familiar with elements of the OODA loop in pop culture. Films like The Bourne Identity, or the recent Bond films show classic outcomes of the use of OODA loop, which is the result of real special operations personnel training the actors and consulting on the scripts and fight scenes.

The tension that arrises from these films, in which we observe someone using the OODA loop, comes from the audience being slower to understand how the protagonists are processing situations. As an audience, we have a hard time dismissing details and living in the moment, so it is exciting to see characters who are unpredictable, and yet acting very logically.

This scene from The Bourne Identity is a classic example of the OODA loop in action.

Here’s another from the classic film Top Gun, handily labeled so you can follow the steps that the fighter pilots are using. This video has an added bonus in that Maverick, played by Tom Cruise, fails to use the OODA loop, and suffers the consequences.

The Monty Hall problem

The OODA loop is a practical tool in decision theory. Probably the most famous case of a practical application is the so-called “Monty Hall Problem.”

The problem was first articulated in the 1970s in response to an American game show called “Let’s Make a Deal.” The problem goes like this:

“Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?”

What’s important here is differentiating between a decision strategy, and a single decision. While the chances of the original choice being correct are indeed ½, the odds that the initial choice would be correct over many iterations are only ⅓. That means that if you consistently stick to your choice, you will only win ⅓ of the time, whereas switching will give you a win ⅔ of the time.

Why?

Think of the problem again, but with different numbers. Suppose there are 100 doors. 99 with goats, and 1 without. Now suppose you picked a door, and the host them revealed to you all 98 other doors with goats behind them. Now do you switch your choice? Whereas your initial choice had a 1/100 probability of success, your new choice, has a much higher probability. This time it’s 99/1.

If you don’t believe me, you can actually test the phenomenon here.

Applying the OODA Loop

Now that we see the difference between decision theory and probability, we can begin to understand better how the OODA loop works. Because it requires that we observe according to the latest data, we begin to see that applying decision theory in real life becomes more practical.

Take this situation:

You walk into a bar, and observe a group of large men in military outfits standing at the bar. The men are sweating profusely and breathing heavily. No one speaks. You see that all of them are carrying rifles or pistols. They appear not to notice you.

Your observation moves to orientation: your judgement says there is probably trouble. Based on the available data, you decide that turning and walking out will draw attention and cause them to panic, or even attack you. Challenging them is too dangerous, as you are alone and unarmed. You decide to continue past them to the bathroom, where you know there is probably an exit.

You get out of harm’s way and look and listen from safety. The men stand quietly. Eventually a bartender appears and they order beer. The men begin to laugh, and one of them explains to the bartender that they are just coming back from a game of airsoft.

Orientation Leads to Better Decisions

Notice first of all that observation and orientation happen always before a decision is made, or an action taken. The decision is then subjected to another round of observation, where the first set of data are taken together with the new set.

We see from this example that quick reactions are, over the long run, less important than correct decisions. Anyone who has been trained to drive a car in mountainous areas has probably been told that the best decision when a deer runs across the road in front of you is to hit the brakes, but not to turn. This is not because turning is unlikely to help you avoid the deer, but rather because swerving away *is* more likely to cause you to crash the car (possibly into another car).

Those with relevant experience know that the deer will mostly likely run away if you slow down but don’t turn. If you turn, the deer can become confused and may hold still, causing you to hit him anyway. Even if you hit the deer front on, this is less likely to endanger your life than a side collision or losing control of the car. Either way, your best decision is not to turn: no reaction is better than an overreaction.

If in the former example of the OODA loop in the bar, you had reacted as quickly as possible to the situation, you would have made mistakes. First of all, you would have suddenly run out of a bar that was perfectly safe. Or worse, you might have attacked a group of men who were armed.

If you had challenged the men, you might have been killed, or beaten. If you had run out, you might then have called the police, causing further trouble, and perhaps even unneeded violence. If you think that’s overselling it, keep in mind that police shoot civilians with distressing regularity, in some countries, for such offenses as holding a mobile phone, or a toy gun. That often occurs because the police are not trained properly – such as with the OODA loop. Your effective use of the OODA loop could prevent that from happening.

Thus, in this situation, a slow reaction was preferable to a fast one, which is why you made a conscious decision to continue to the bathroom, rather than to engage with a situation you didn’t understand yet. You then moved back to observation and orientation. Discovering that the men are just coming back from a game, you may decide that no further action is necessary. If the new situation, by itself, does not appear dangerous, you may then decide to dismiss your concern, or you may decide to continue to observe.

OODA for Entrepreneurs

As Malcolm Gladwell points out in his book Blink, which explores decision loops in human interactions and business, as well as in historical conflicts, an ability to continually orient to one’s current circumstances is the greatest predictor of failure or success- a predictor more powerful than numerical data or objective observations.

Consider how this can be applied in the thinking of a small business. In the fact of numerical advantages, or sudden threats (such as bad PR, or even a troll on twitter), to what degree is your decision making purposeful, and designed to accomplish a known goal? Are you capable of altering your strategy to take advantage of new information and new events?

Observing new facts is easy to do. But consciously challenging an existing mental model is much harder. Reacting to data only after deciding *how* to react, can make the difference between a major gaffe, and a well-handled situation. Those who are able to act according to the most relevant information in any given moment are likely to win in the long run. Just as in picking stocks, or playing poker, success is found in not allowing your initial strategy alone to determine your future actions.

As John Boyd himself put it, to paraphrase: “in any game, the winner is most likely the one that can orient to new developments and alter their decision making as a result.”