Meet Printsyst: The Only AI 3D Printing Expert You’ll Ever Need

/in Interviews, Startups, StartupYard News/by StartupYardPrintsyst co-founders Itamar and Eitan Yona are brothers, and they represent our first startup from Israel as members of Batch X. They are also the 3rd generation in a family of a printers, carrying their family tradition into the realm of 3d printing. Their startup, Printsyst, is for companies that use 3D printing, but don’t have internal expertise. PrintSYSt is an AI-powered management solution that provides a complete automated 3D printing workflow. Unlike standard existing solutions, PrintSYSt requires no expertise, allowing users to focus on design instead of production.

Itamar, the older brother at 34, plays the role of CEO, and has a degree in Electrical Engineering. He provides professional engineering advice, lectures, and workshops about additive manufacturing worldwide. His articles being published on well-known industry magazines and blogs. Eitan on the other hand focuses his attention on marketing and communication, and can be found frequently on the team’s YouTube channel, connecting with experts and educating his audience on 3D manufacturing.

Printsyst Co-Founders Itamar (left) and Eitan Yona (right), with StartupYard CEO Cedric Maloux

Hi Eitan and Itamar. You are not actually our first pair of siblings at StartupYard, but I think people will be interested to know how it is you both came to make 3d printing your focus in life. What’s it like to do this together?

We will answer these questions in one voice, because that’s really the way we are as a team. We know each other so well, it’s like one hand working with the other. It’s muscle memory.

Working with family is unlike anything else. You can have colleagues, and you can have people whom you rely on and you trust, but these are not your family. We are a 3rd generation family in this business. Our grandfather was a printer, our father is a printer. We are carrying that tradition forward, and in that sense we see ourselves as a part of that tradition, just bringing it forward.

Our father taught us growing up that individually, we would never have the strength that we have together. Perhaps you can tie this in with the history of our country and people as well. We have to cooperate as one to get things done. As brothers we are able to learn collectively, and to multiply our strengths.

That is the secret sauce in a family business, which is that you are building upon a foundation that is rock solid. In most tech startups, we think this is missing. That sense of belonging to the industry and the sense that you are born to do what you do is very appealing. Our family is not just in the printing business, but rather we are in the technology business, and always have been. The technology just changes. The business part is not so different.

It’s fun as well. We can laugh at and scream at each other, and change directions in 10 seconds. We don’t have to forgive each other for every mistake. We can be angry, and we can share our feelings with each other. One can rely on the other.

Is there a downside to the family dynamic?

Sure. We are very monomaniacal about our work. It can be hard to stop talking about work and switch to other topics. How are your kids? What did you do this weekend? We get very comfortable talking about work topics, to the point where the separation of work and life is a bit blurry.

But again, this is in the family for generations. Our parents worked together all our lives, with our grandparents too. Life and family is business. There is no distinction sometimes. I don’t know if you consider that healthy. Maybe it’s good for some people and not good for others. We make it work. We are happy with what we do now.

Do you think that family background, being a 3rd generation printing family, gives you an advantage over others who come into this business from a different background, such as in computer science or manufacturing? What are the intangibles of a printer’s life experience?

So, it’s important to emphasize that we are technologists, by tradition. Printing is just the technology we know. A family business is not something that should stay the same for all time. That is not progress. Instead, a family business gives you the roots you need and the stable base you need to grow with much higher confidence and the right connections from the beginning.

It may seem like we are departing from tradition. Our father and grandfather were in 2D printing (Printing Press). We are in 3D. It’s a different world. However, our father made the switch from offset to digital printing. That was equally difficult, and equally transformative in its own time. The needs of customers change continually, and having a deep empathy and respect for people is something that takes a lot of life experience.

In that sense, what you do in 3D printing is no different at all from any other kind of printing. People always have the same flaws and the same needs from you. You are the person helping them to take advantage of the technology and see what is possible for them. If 50 years ago it was that they could print a photo or a book, today it’s that they can print something like a pair of glasses. Still, you serve a human need: to start a small business, to realize a creative dream.

That human level is where everything important is happening. The business that can get down to really sharing a bond with the customer and understanding and appreciating them for what they are, is going to be successful. The money will follow. That’s our view.

It seems rare to me in technology to see people follow their parents as role models and mentors

Yes, it is more rare than it used to be. Technology is no longer seen as a trade, but rather as a skillset. So you are not a craftsman or a journeyman, but an engineer. That brings the focus out of customer-minded, traditional practices, and toward institutional ideas and practices. The engineer thinks as the university teaches him to think. Not as his father teaches him to think.

That is not always bad of course, but there is a reason that trades have been passed down from

parent to child for all of time. In the formalization of some knowledge, you will lose that which cannot be written down. I can teach you to code out of a book. I cannot teach you to run a business out of a book. I cannot tell you what use that code will be once you know how to do it. That is experiential, and it is something people can get from their parents, and should get from them.

So in a sense you would like to see the tech business be more conservative?

Maybe. What does this mean, conservative? There is simply a great deal of value in growing up in an industry, just as there is value in coming into an industry fresh with a new perspective. Both approaches must always be considered.

In the “entrepreneur industry” today, ego is heavily monetized. Right? It is all about the founder and the singularity of them and their vision, and how no one else is the same as they are. No one can do what they do. But this is nonsense. This is not how knowledge is gained in the real world or passed on for our shared benefit. We are not islands to ourselves. If you build to last, then what you build is more than you are.

When you look to the great fortunes of the 21st century, it is sad in a way that they belong to people who are in many ways isolated in time and place. They have no sense of their past or future. Disruption in the sense that the technology industry means is often just an ego trip. Technology always changes. It is a question of whether we are better as people, or worse. Do we do good for people, or not?

What attracts you to working on 3d printing in Europe? Why not somewhere else?

Well, of course we were attracted to StartupYard! But also the fact that Europe is a really fertile ground for change and innovation in 3D printing. We see it as somewhere that we can bring a lot of value, and where businesses and people are ready to take advantage of our technology.

We love Israel as well, so we will always be home there. However, 3D printing is not like the old printing business. It is language independent. It is global and digital. So we must be where other companies are doing this work. The business may be global, but being physically present is still very important. We have to make ourselves unavoidable and inescapable for the future of 3d printing.

Let’s talk about the technology because I think most people see 3d printing in a really simplistic way. What is the current state of 3d printing, if you can provide some analogy to traditional printing technology? Are we in the Gutenberg days? The Franklin era?

Yeah, that’s a good question. So decades ago, when our father was taking over the family business, there was no really good software drivers available for professional, quality printing. People who were going digital were doing this stuff on their own. You had to have a very good reason to do that, because the change was very drastic. It was essentially taking everything that you know about printing, and changing all of it.

You want to print digitally? Ok. You need a team of developers, hardware engineers, you need a lot of money to research and test. You basically have to start from zero. People cannot imagine this now, because today you don’t think about PostScript and print drivers, and these things that were hell on people in the printing business for many years.

You have to consider that digital transformation is not a new phenomenon in 2018. It has been going on for decades already. The journey from an offset press, with physical plates printing pages, to a digital laser printer is an enormous change. It is like going from steam power to electric. Everything must change.

Now we face the same level of challenges in 3D printing. To digitize the making of 3D objects. If you will, I think we are in the offset printing era right now of 3D objects. You have injection molds. You have industrial processes that take huge investment and planning to work. You do have 3D printing happening on a small scale, but you lack all the hardware and the essential drivers between the finished object, and the technology itself. And if you are lucky enough and have access to 3D printing, you still need to follow a long learning curve.

That is the problem we are solving at the end of the day. The ease with which you print a page of paper today should be, maybe 15years from now, the same ease you experience printing a pair of glasses or a new doorknob. Whatever you need. Remember printing evolved from handwriting to the printing press, to the digital laser printer in more than 500 years. Manufacturing also is taking a journey from the handmade to the ubiquitously available object in a similar space of time.

Obviously there have been some hype bubbles surrounding 3D printing in the last few years. Do you think we are poised for a major step in the adoption of these technologies now?

It’s true, particularly maybe 10 years ago, that there have been some hype and disappointment around 3D printing. This is necessary to the process, And predictable in a way.

This is a normal thing for new technologies on the adoption curve.

There were lots of ideas, and people doing very cool things with 3D printers, but the technology has not jumped to mainstream adoption for a few specific reasons.

One of them is the materials being used, and that is changing very quickly. People found pretty quickly that the variety of objects and functionalities was limited by the material. Color, strength, consistently, etc. There are many new approaches coming to the physical printing process that will make this much easier.

On the side of software, this is what we are trying to solve. One of the problems that emerged very quickly was that there are many physical parameters to consider when you are printing an object of any size.

Unlike on a piece of paper, you have an object in 3 axis, and you must consider the 4th dimension as well: in which orientation should parts be printed, and even more, what should the internal structure of the parts be?

So that is where AI comes in?

Yes, precisely. AI is needed to run through all these potential variations in the way a thing can be printed, and select the best one for the purpose at hand. That can save a very lengthy process of having to manually determine these factors, or just guess and check to see if it works, which is what people are doing today.

Many hobbyists quickly found out that they could not move from imagining a new object to simply printing it, because the technology required more detail than the imagination supplies. You need hundreds or more parameters to print a 3D object. You must know the thickness of each component. You need to choose internal structures (honeycomb, swiss cheese?) you must know in what orientation to print, and where the piece will be separated from the printer. How fast will it be printed?

So the process of iterating these tiny details in a physical printer is very expensive and time consuming. There were many cases in which people just couldn’t produce prototypes because they couldn’t get the printer to follow a process that created a stable object. That’s a big problem in 3D printing. That’s not a physical obstacle, it’s a software obstacle.

We are using AI to sort that problem out. You have to virtually simulate the infinite combinations of possible approaches to printing an object, and find that ideal process, which is going to be absolutely unique for every single thing you print. One small change to the thickness or the length of something, and a 3D printer must be completely reconfigured to allow for printing a stable version of this new design.

That really destroys your ability to iterate, unless you can be sure that each time you print, you are getting the best version of the object you are trying to make. You can make quite complex parts in 3D printers, and in some cases these parts can serve to replace dozens of other components that were formerly separate pieces in a machine or a piece of furniture. But if you can’t figure out how to stabily print that object, then the 3D rendering is useless. It’s just an idea.

Printsyst is taking that rendering, and making it printable and stable, and useful from the first try. That’s the objective. Break the expertise barrier that stops people from using 3D printing for whatever reason. Democratize manufacturing and make it something accessible to small businesses, entrepreneurs, and individuals.

We know that 3D printing has huge applications for manufacturing and design (such as being able to rapidly build custom parts and eliminate assembly steps). But what kind of impact do you see on consumer lives in the next decade or so?

Much of the impact may go unseen for the near future, to the end user. Many things that were formerly very complex to assemble may begin to be 3D printed, such as electronic components and even parts for cars, furniture, and things like that. But you may not know the difference if you don’t know how to look for it. It will simply allow businesses to deliver these goods cheaper, faster, and in more variety.

Later on, as this technology is further democratized, it can have the same effect that widespread printing had on the spread of literature and businesses around the world. The ability to create something fast, cheap and in good quality with minimal equipment also means you can take a lot of creative risks, and many microbusinesses may be born. Already you see this among some designers, using 3d printing as a bit of a gimmick. It will not be a gimmick forever.

Ultimately, we probably get to the point where an individual is able to order or print parts and object themselves that are customized to their exact needs or the needs of a situation. You know what size shoe you wear, but I bet you don’t know the distance between your temples. So why don’t you? Because knowing that, you can create a pair of glasses that fit you perfectly.

3D printing will mean “mass customization.” This means less waste of energy and materials, less cost to transportation, and ultimately we believe a better environment in which fewer resources are ultimately wasted by overproduction and under-customization.

How can companies who are employing 3D printing start to take advantage of your technology? Where do they get started?

Right now, we are working with small and medium sized enterprises who are using 3D printing to develop and produce new products. These companies don’t have a lot of internal 3d printing expertise, but can bridge that gap with Printsyst.

We also are interested in working with designers, and other entrepreneurs or engineers who want to use 3D printing, but again, don’t want to lose a lot of time learning how to get the most out of a printer or a particular design. We would love to support efforts to build low cost housing, and there are currently many needs from many different types of printers to get them to run more efficiently, and to optimize designs on the go, making each printed part perfect for its exact position and purpose.

Some industries we see getting interested are especially interior designers, architects, and automotive repair as well. 3D printing is great for refurbishing cars or making customized components, so we should see a lot more interest in that direction. Replacement parts, particularly, can be made much faster and exactly to fit.

In the long term, we really believe this technology is going to penetrate everywhere. Eitan spent his military service on a submarine in the Israeli Navy, working mostly on repairs. Imagine having a 3D printer in a submarine so print the exact parts you need. Stock becomes a much easier logistical issue.

Meet Urbigo: Your First Smart Home Garden from StartupYard Batch X

/in Interviews, Life at an Accelerator, Startups, StartupYard News/by StartupYardWith each new batch of startups at StartupYard, we run a series of detailed interviews with the founders to give our community a sense of who they are, and how they see the world they’re trying to change. Last week we announced 7 new companies in StartupYard Batch X. Today, we jump in with an interview of Anja Varnicic, CEO and Co-founder of Urbigo, the urban smart garden company that promises to “Bring nature closer to you.”

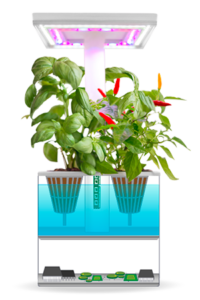

Urbigo is a system including a small modular garden with grow lights, and cylinders for plants containing nutrients and water. The garden is controlled via an interactive mobile app, and users can get the latest advice on how to tend to their mini gardens, as well as order new plants, nutrients, and soil packs from Urbigo.

CEO Co-founder Anja Varnicic, shows off Urbigo’s Smart Garden with company CTO and Co-founder Aleksandar Varnicic

Hi Anja, coming from a plant biology background, what made you want to turn your passion for the science into a business, helping people grow plants at home?

So, as an environmental scientist, I have long asked the question: “what role do plants really play in our lives?” The truth is that we are entirely dependant on them. For oxygen. For nutrients. For flavor, and for our wellbeing. Yet modern society has moved off the farm, and now treats plants and spices as commodities that are easily fungible between one brand and another. If not from Spain, then from Brazil. If not from Turkey, then from California.

We don’t understand where our food and our air comes from anymore, and I think that is a problem for people living in cities. Of course, we can’t expect people all to live in hydroponic greenhouses in their flats, but we should get ourselves closer to the foods that we eat and the flavors that we taste.

The way of doing that for us at UrbiGo has been to bring just a little bit of green into people’s lives, and to show them the immediate benefits of tending to plants that we depend on for everything. We came up with a focus on spices that can be grown in the urban kitchen, because not only do fresh coriander or mint taste better than dried and packaged versions, but also getting something to eat directly from a plant in your home reminds you of the life behind the things that you eat, and the natural world you depend on.

As with any other true love story, the startup idea happened unexpectedly and accidentally. I wanted to make these ideas into a real business. Luckily enough, I had a chance to share my business idea with Alex, our now CTO, who had previous startup experiences. We shared our thoughts, he loved it, and boom – UrbiGo was born!

How do you think incorporating gardening into one’s everyday life can affect positive change for somebody living in a city?

CEO Anja Varnicic is an environmental scientist and an engineer.

They say plants are the friends that always listen. And they really do. Indoor plants and urban gardening has become madly popular in the past few years because it reduces stress, make our air cleaner and our bodies healthier. And those are the thing we usually forget about or take for granted.

Having and growing fresh ingredients from your own garden is a creative activity. It brings us the same feelings we have as in making a sculpture or a painting, or writing a song. Gardening is viewed in Eastern cultures as almost poetic in nature.

For the millenial generation, we want to feel that connection to the Earth, and doing so makes us feel more responsible and more connected to nature. It makes us feel like grownups to be able to make life in an urban area where nature has seemingly little control.

I also believe that the millennial generation regrets the excessive commoditization of food. We yearn for the experience of knowing how our food is made, what it is, and how it makes its journey to our plates. So you see many different ways this is expressed in the modern consumer culture. Farm to kitchen restaurants. Farmer’s markets. Home gardens, and smart mini-gardens like Urbigo, that will help people to get back some of the control that we have lost over our diets and our environment.

]What would you say are the biggest mistakes we make when it comes to designing urban homes, and thinking about our living environment?

]Today, a larger share of younger urban residents live in rented flats or flatshares than have ever done in the past. What we see happening in cities is interior spaces being divided into smaller and smaller parts, and unless the presence of plants is part of the planning for those spaces, it ends up as a kind of afterthought.

Take a walk for example through an Ikea, which is where a lot of young people are going to get a sense of how to use their personal space… the plants are the last thing you see there. They are the afterthought. They are what you add when you have everything done.

This is backwards, I think. We need to plan more around plants, and plan to live with more plants in our personal spaces. That can affect the placement of windows, or the whole design of a building. The use of light must be reconsidered. In some cities such as Paris or Berlin now, whole buildings are being constructed with plants on their walls and rooftops. This is a good start.

Do not treat plants as a pleasant addition to your home. If you do, you will not have room for them when you decide they are the thing missing for you.

Let’s talk more about Urbigo’s products. What would you say distinguishes you from other indoor gardening solutions? What is your “killer app?”

UrbiGo isn’t just a fancy smart garden that grows fresh herbs for you – it is a community of plant lovers and enthusiasts that are changing urban gardening as we know it.

UrbiGo gardeners get to control their UrbiGo mini smart garden from their phones and learn how to grow their own fresh and nutritious ingredients in a fun and simple way through a gamified app. By completing daily challenges in the app we want to motivate and empower people to become successful urban gardeners and live more sustainably.

We take some cues from products such as FitBit, or Calm, an App for managing stress and relaxation. The way they engage millions of users into doing something good for their body and mind is something we can learn from. Tending to your garden should be a small but integral part of your daily ritual, and with UrbiGo app we want to make the process learning and enjoyable even for those who could kill a cactus.

The Urbigo App

Now is an interesting time for home gardening, because today urban millennials are becoming used to healthy lifestyle daily rituals using technologies like smartphones and watches. We don’t want to suck people into paying attention to their phones, but rather to use the medium of the smartphone to help people live a healthier and more satisfying life, and live in a better environment.

Suppose that urban gardening becomes the norm for people living in cities 10 or 20 years from now. How else would you like to change the way we design our lives around food, cooking, and living spaces in the future?

Since we tend to spend most of our days in offices and indoor spaces, I believe it will be essential to stay connected with things that matter most like family, friends and nature. Plants and greenery have this power to gather people, especially in urban areas where those are scarce. And we wanted to make this values approachable and simple for our users which inspired us to create product and a network of like minded plant lovers and untaped enthusiasts.

Many people living in cities rarely if ever buy fresh spices and ingredients for cooking. What are they missing out on? What are some of the concrete benefits of growing at home?Besides improving your overall health, growing and consuming your own fresh ingredients makes you connected with nature and origin of your food, that obviously doesn’t grow on market shelves and from plastic packaging.

We’ve heard lots of complaints from our customers, that store-bought herbs dry out in a matter of a few days and don’t have the fresh and intense tastes they’ve come to expect. Once you have something fresh, it can be very striking to taste the difference between that, and something not fresh. So I think people should have more choice about what to consume and when to consume it – this is why the UrbiGo app educates consumers about the benefits of “growing your own ingredients” so you can make proper decisions about your health and wellbeing. Be better informed, and make more informed decisions.

Food gardening is most of all a local and sustainable way of producing fresh ingredients and educating your family on where your food comes from. As cities transform into concrete jungles, this kind of relationship with nature will become crucial for us future generations’ well-being.

As a business, where would you like Urbigo to be 5 years from now? What will be your metric for having accomplished your mission?

We go where our customers needs are, and thus we are experimenting with the ways to include smart indoor gardening into every future home. The next logical long term step would be to incorporate UrbiGo into the smart home device network because there is a space and interest in companies for the next gen “plant device” that would improve urban health and connect with their low-friction lifestyles.

For now our goal is to get a smart garden into every home, and turn that into a network of people who are thinking much more about their well-being, health and importance of food gardening.

Imagine, using smart home technology to, in a way, bring us back to an earlier age when you would ask your neighbors for an egg or a cup of sugar. Maybe in 5 years you will be able to use UrbiGo to compete in urban gardening skills with your neighbor, grow chillies in your office desk or have a “green pet” for your kids. Maybe it will lead to people sharing much more of their domestic lives and spaces with each other, and helping each other to live better.

I think these very locally focused changes will be a very important part of the smart-home of the future. Not that you are one home connected to the whole planet, but that you are one home connected to the homes around you as well. We all share one environment, and the best way to improve it is to connect and learn together.

You’re employing a number of new technologies in Urbigo’s gardens already, like 3d printing, and LED lighting. How do you see technology making urban gardening even easier in the future?

New technologies have allowed urban gardening become more “smart” and resilient to climate change effects we are experiencing. So you don’t have to be dependent 100% on sunlight, ever changing weather conditions or your personal skills and knowledge .

But, still, people don’t want technology to do everything for them, because growing and tending plants can be part of a soothing ritual as well. I see technology as a tool to make your everyday life greener, easier but also to empower you to learn and share your urban gardening experience with others. We cannot stop urbanization, but with technology we can help people stay connected with nature.

Has there been a major surprise for you since joining the StartupYard program? Did you learn something you weren’t expecting to?

I’m not sure if it was a surprise, but we have certainly noted that the interest in smart gardening in the corporate and business spheres are also growing very fast. I think as millennials begin to move higher in large organizations, this is going to become an area where we can have a big impact with our product.

The Urbigo Founders brought some life into StartupYard this round

People spend up to half their time in offices, and in many cases, these spaces are poorly adapted to keeping people healthy and happy. Companies are understanding more and more that the total wellbeing of their employees is a vital consideration, and that if they cannot provide a better environment for people, then workers will go to those who can. I think this is very positive, and I hope to continue to raise people’s standards for their immediate environment, and inspire people to demand greener workplaces.

What have been your team’s biggest personal or professional challenges in making this project a reality?

We’ve been able to grow the waitlist for UrbiGo to over 500 people and we got major interest not just from individuals but also corporates. One of the challenges for us, as we are engineers, was to let go of some of our ideas about what people should like, and really listen to what our customers are saying about what they want.

You can come up with great ideas, but if you can’t get your ego out of the way, you will miss the experiences and stories that really define who your customers are, and how they see your products fitting into their lives. Learning this at the beginning of our startup journey was crucial to get first sales, traction and investments.

We cannot stop the technology and urbanization, but we have to design a product that accommodates our customer’s fast paced life and needs and also engages them into doing something little everyday that is good for themselves. This is an ongoing process but we are happy that so many people help us do that and share our vision.

What do people need to get started with their own urban gardens? How can they get their hands on an UrbiGo smart garden?

Since UrbiGo does not require big space, plant knowledge or time but accommodates to your lifestyle, you are basically one click away from starting to grow your mini indoor garden.

We have had testers out in the field for a whole, and we’re ready to go live. Right now, we are taking signups for a special, limited first batch of Urbigo gardens for those real enthusiasts who are ready to join our smart urban gardening community. This exclusive run will start delivery in December 2018, and the wider public will be able to order from Urbigo during the next year.

Guest Post by Ondrej Krajicek: What It Means to Be a Mentor

/in Interviews, Life at an Accelerator/by StartupYardAbout Ondrej Krajicek

Ondrej Krajicek is Chief Technology Strategist for Y-Soft, and Y-Soft Ventures, a Brno-based printing and 3d manufacturing tech company where he has been a team member since almost the beginning. Ondrej is a dedicated startup mentor, and a longtime member of our community, where he has published his thoughts and unique perspectives on the technology business and other topics many times. Today Y-Soft is one of Czechia’s few technology “unicorns,” and serves large and small companies all over the world. At Y-Soft, Ondrej considers it his mission to grow the Czech economy by encouraging technologists to focus on crafting superior products and relying on their best skills, rather than focusing on cheap labor and manufacturing.

What It Means to Be a Mentor

Thank you StartupYard for giving me the opportunity and looking forward to the next cohort.

I should have started writing this article after my mentoring day at StartupYard, which is November 21st. Having past experience with several cohorts, I just could not resist and started as soon as I got the idea. So it is rather sunny day in Texas and I am looking forward to working with StartupYard and the incubated startups once more. I am writing this to give myself more clarity on why am I doing this, what should I deliver to the startups I am going to talk to and what should be my take aways from the day. I also have a tiny ambition that this may change somebody’s perspective on mentoring and improve the experience for any mentors out there and those being mentored as well.

I have been working with StartupYard since 2014 and it has been a tremendous experience. They truly have a great team with three people who really stand out: Helena who handles all the scheduling, Lloyd who does a great job with no-nonsense PR (a true rarity in Europe) and Cedric, who leads it all.

You are not the smartest guy around…

I will never forget two immortal quotes from Bohumil Hrabal in Slavnosti sněženek: “Máte štěstí, že jedu kolem.” and “Říkají o mně, že jsem odborník.” Apologies for Czech, it really never gets old.

10 years ago, having been invited to be a mentor, I would probably feel honored and entitled. If repetition is the highest form of flattery, than asking someone to be your mentor is definitely the second highest. And after the thrill of being asked to mentor dissipates, the first thing I need to consider is my responsibility to the teams I am going to work with.

Being a startup team in a world class accelerator is an overwhelming experience. There is little time for everything and spending time with a mentor is an important investment on the team’s side. They are investing time, energy and money in that discussion, regardless of its length. And as a mentor I should never forget that.

I am not a mentor because I am the smartest guy around. I am not a mentor because I am successful. I am a mentor because I had to solve problems, perhaps similar problems in different contexts and I, my team and company survived to see another day.

So how can I make sure that the discussion is worth their while?

Be Useful

One of the best mentors I had the chance to meet, Ken Singer taught me one of the key principles of Silicon Valley: Pay it Forward. If someone seeks your help, help them — without expecting anything in return from them. Someone else, some other time, will help you too. Next time you are pondering how to replicate Silicon Valley success in the Czech Republic, think about this and the culture which is preventing this simple approach to take of here.

How does this apply to being a mentor? Do not expect any tangible benefit in return. You will not get shares or money just because you graced someone with your presence and shared your experience. Certainly not by answering few questions.

Being useful means adopting the mind set of freely sharing anything and everything which feels relevant to the situation. Connecting people with people.

Tell Stories

The real problem is that sharing is difficult. Robert Kaplan gave a great talk about mentoring which is available on YouTube.

If there is one principle I need to follow, one thing to take from Robert Kaplan, than it is that I should not tell them what to do. Kaplan claims that mentoring advice is only as good as the story, but what if it’s you telling them stories. Stories are about context, problem, solution and lesson — just like bedtime stories of our childhood. Just this time, it’s about business.

Instead of asking them to tell me their story and risking, that my advice would only be as good as their story, I should tell them mine and let them take what they feel they should.

I see mentoring as a form of leadership. This is the less obvious kind where I do not manage anyone, certainly not the team I am talking to. My biggest power over the team is listening.

That is easier said than done.

Ask the right questions

I usually start with three questions:

- How can I help you today?

- What can I help you with?

- Can I have a whiteboard please?

But no, these are not the right questions. As Kaplan teaches, leadership is about finding the right questions and my “right” questions are about users, employees and customers.

- Why is anyone going to pay you for your services or products?

- Why should people work for you?

- Why should your customers choose you and not your competitors?

The hard part is not asking these questions, but feeling the answers.

Own It

In 2015, Harvard Business Review published a nice article about how it is impossible to put yourself in the proverbial shoes of your customers. Cutting to the conclusion, I am not trying to put myself in the shoes of their customers.

I need to become one. This is where my stories help. May be, sometime in my past, I was in a situation which would require products or services of the team I am talking to today. My experience, if it is relevant, kicks in when we start debating the need, the constraints involved and how is their solution solving the problem. Which is now — for the time being — also my problem.

Mentoring is like acting. I love theatre: drama, comedy, opera, but I would be terrible actor. But here I can immerse, I just need to be authentic.

Share beliefs

Authentic means that I need to tell them the truth. Not that I expect to lie or think that some mentors lie, but if I am not authentic, they cannot trust me and probably won’t. This is not a place and time for rhetorical alchemy as I am not here to influence: no careful dosing of ethos, logos and pathos. I am a stand and a big bazaar and the mentored team shall pick only what they like. I am not a major stakeholder as I am not materially vested in the team’s success. I am here as a volunteer.

Acting, management and mentoring are alike at least in one more thing: filtering does not work. So how should I establish authenticity? I need to share my beliefs. How can I prove myself? By story telling again. After all, marketing is all about proof points, isn’t it?

When the team shares my beliefs and values, they understand my story and how is it relevant to their products and services, they are in the position to take some advice.

Teach? Share failures!

Merriam-Webster defines the noun “mentor” as a trusted counselor or guide. Having the right context from the team, being their customer at the moment and consistently with my beliefs and values, I am ready to share advice. What I did and how it worked. What I did and how it failed.

In my experience, the best way to share knowledge with others is to share your failures. When I succeed in something, I am seldom completely sure why I succeeded. When I fail, sooner or later I find out why exactly I failed. Failing gives me clarity and confidence. I am never giving up and I dare say that I learned to patiently and diligently study the failures I was part of, my failures or failures of my team.

That clarity and confidence also enables me to share it with the team. It is their choice whether they want to repeat mistakes of others or make their own mistakes.

Not that I agree with the failure worshipping, which seems to be a thing in the startup culture. As Tomas Sedlacek put it in his tweet, I strongly preffer trial-success than trial-error. I also believe in failing fast and measuring hard, which I will probably never fully learn.

And I am not as selfless as it may seem. There has to be something in this for me.

Why am I here today?

Mentoring is a learning experience, so first and foremost, I am hear to learn. Occasionally, I learn about new approach, business model or technology. I used to focus on that.

Today, I am here to train. To stretch my muscles in a different way than I am stretching them every day at work. If you ever exercised with a trainer, you know that your trainer is changing your exercise quite often. You are doing something else on Tuesday than you did on Monday.

Change is good as human body excels at adaptation and always finds equilibrium of achieving results with minimal energy. Human brain is no different and is actually great at building and making mental shortcuts. I am here to train active listening skills in extreme conditions (time is short), maintain an open mind and apply what I know on problems I do not have. I am here to push myself for patience, which is one of my biggest weaknesses.

And I am here to relax. Other teams and other people struggle with difficult issues too. Others are also trying to do what they believe in.

I am not alone in this.

SY Investor Launches DOT Glasses: The $3 Glasses That Could Help the World See

/in Interviews/by StartupYardOver 1 billion people in the world need glasses, but can’t afford them or don’t have access to them. That’s why StartupYard investor and mentor Philip Staehelin launched a Czech startup – DOT Glasses – to try to solve this massive problem 3 years ago.

Today he believes they finally have the solution, and are about to launch large-scale production of the world’s first, one-size-fits-all eyeglass frames (which were designed by a joint venture of Mercedes-Benz and AKKA Technologies), along with a transformative lens concept.

Philip is the former CEO of CCS, the former Managing Partner of Roland Berger, and an alumnus of many other international companies like Accenture, T-Mobile and A.T. Kearney.

Earlier this year, DOT Glasses received a “matching funds grant” from CzechAid (up to CZK 5m over 3 years), and they’ve recently won a place in the EU-funded Startup Europe’s Soft Landing program to India (called the “Ecosystem Discovery Mission”). They were one of the 24 European representatives selected for the program.

I sat down with Philip this week to talk about the launch of DOT Glasses, along with the crowdfunding campaign to support the company on hithit (you can check the link to contribute). Here’s what he had to say:

Lloyd: Why glasses?

Philip: There are a few parts to the story, of course. If you’re asking specifically why I decided to focus on providing glasses to people in developing regions, it’s just one of those weird coincidences that suddenly made me realize that a 700-year-old industry could still be disrupted.

If you mean, why glasses and why provide them to developing regions, it’s because I’ve long been focused on making an impact beyond my immediate “bubble”, and I was at a stage in my career where I wanted to use my time and resources to help those most in need of things we take for granted here in the developed world.

The idea specifically came to me while I was skiing, and it’s funny because at first it seemed like a pretty first world problem to have. I’m mildly nearsighted now (although I used to have very bad eyesight, and had laser surgery 15 years ago to correct my vision), so I wear glasses. I can do without them, but I like the world in sharp focus.

Philip Staehelin, Founder of DOT Glasses

When I ski, I don’t like to wear my glasses under my ski goggles, so I usually go without – which isn’t always good especially when skiing moguls. On the ski lift, I was daydreaming about buying some “off-the-shelf” lenses to pop into some specially-designed ski goggles, providing me improved (if not perfect) vision to make my skiing more comfortable. I didn’t want to spend money on prescription ski goggles – it wasn’t worth it, and it was a hassle – but I started thinking about what could be “good enough” vision and how I could stock some limited range of lenses on the shelf next to ski goggles, so people could just select what lens helped them enough.

The next ride up on the ski lift brought me a eureka moment. “Good enough” vision was all about smartly limiting the selection of lenses. It’s kind of like the 80/20 rule that’s prevalent in so many facets of life and business. 20% of the effort for 80% of the gain. 20% of the lenses to achieve 80% of the vision clarity. If it was true (and the implications came crashing down on me all at once)… it could transform an industry. But not the ski industry with a few million customers at best.

Rather, it could disrupt the eyeglasses industry for people in need. Actually, “disrupt” is the wrong word in this case, because more than 1 billion people need glasses but have no access to them or can’t afford them. So there is not a current player to disrupt. It’s more about tapping into a new, massive customer segment that has been unaddressable because of the challenges of costs, logistics, lack of optometrists, etc.

When I got back home, I started researching the issue. You may think, living in Europe, that we are drowning in optometrists, because they are on every corner of every major city. Actually we have something like 1 optometrist for every 3000 people, and about 60% of those optometrists are usually based in the capital cities.

On the contrary, in many underdeveloped regions, such as in parts of Africa, there are not enough optometrists to go around. In some cases, there are only a handful in an entire country with millions of people. In Ghana, there are about 50 optometrists for a population of nearly 20 million, and the per capita income is less than a dollar a day. Getting glasses can take a week’s travel and several months’ wages.

Which means that for a vast swath of the world’s population – glasses are either an unaffordable luxury, or they’re simply not available. If you have +/-1 diopter (also known as 20/40 vision), you can absolutely live a normal life. In the UK for instance, 20/40 is the required driving standard. But once you start getting past +/-3 diopters (20/250), it starts to become difficult to lead a normal life. I have first-hand experience, as I used to have -6 diopters before my laser surgery, and as a kid, I literally couldn’t find my family at the beach if I didn’t have my glasses.

That’s so interesting. Basically there is no existing market to help these people.

Exactly. Poor vision is the #1 health issue in the world, but almost no one talks about it. It causes roughly $230 billion dollars of economic loss every single year, but on an individual level, poor eyesight prevents people from learning in school, it prevents them from having a meaningful job (or any job), and it hurts families and communities. Poor vision literally traps people and families in poverty. But it’s been too challenging to treat poor vision in more remote parts of the world, even though the solution has been around for centuries.

So in the end I decided on a simple concept (I actually call it “maximum simplification”): a set of glasses that are both modular, and cheap, which can reach developing regions fairly easily, and don’t require a professional optometrist to be dispensed to the end user. All you need, to provide a pair of customized DOT Glasses is a very simple testing tool (that we developed), and the components of your individual set of glasses: the 6 pieces of the snap-together frames, and the right strength of lenses (which, by the way, are “left-right agnostic” – a concept we also developed, allowing for the same lens shape to be used as a right or left lens, which reduces lens stock requirements by half). The end result: robust, good-looking, glasses that are available to a buyer for about $3.

$3 is a lot to some people

Yes. If you live on $2 a day, then $3, comparatively speaking, is pretty close to what a person in the developed world would pay for their own glasses from an optometrist. We have worked very hard to make them as affordable as possible, and $3 is the lowest we’ve been able to get it. For those wanting to correct a less severe problem with their eyesight (e.g. -2 diopters), this price point may not be absolutely compelling, but for the more severe cases, it’s the best investment they will ever make. It will be completely life changing.

Why haven’t charities really attacked this problem before?

They have – there have been many projects targeting this problem, but none has been able to address all the issues needed to scale properly. Those that train optometrists are doing a great thing, but the world needs about 100,000 optometrists to bring the per capita ratio even close to a 1st world ratio… and they still wouldn’t be located in rural areas.

There are a lot of economic incentives against optometrists locating themselves in poorer areas. They go where people can pay more, especially if they are in high demand. That means you can train thousands of new optometrists and still have little impact in remote regions. They will go where the money is.

Others focus on delivering self-adjustable glasses with some fairly advanced technologies (two stand out: fluid-based lenses and Alvarez lenses). But in reality, these are over-engineered which keeps costs much too high. They deal with one shortage (optometrists), but they exacerbate another shortage (money). And they don’t look like normal glasses – they’re simply not fashionable enough.

Those that attempt to solve the problem by providing regular glasses as cheaply as possible still run into issues such as: huge stock of frames and lenses needed to address all of the combinations of faces (including pupil distance and ears distance from eyes) and eyesight requirements. This increases the cost of stock, and makes replenishing that stock much more complicated and costly, but it also requires a trained optometrist (or at least an optician) to measure the eyesight to a fairly granular level. All of this adds complexity and costs, which makes it impossible to propagate into more remote rural areas.

Also, I think one of the big problems with the all-charity approach is that they often fail to take the motivations of the people they are working with into account. If you develop real economic incentives for people to distribute the glasses as a product, for example, by supplying a few local people with the training and the equipment necessary to dispense them, then you are effectively creating a new market. That’s the reason we developed our own super easy testing kit as well, because at the end of the day, we want this to be a new viable small business opportunity for people in these remote areas, where previously providing glasses was not economically feasible.

That is why the glasses are not free to begin with. If we relied on charitable donations, we would also miss out on the opportunity to leverage the entrepreneurial energy of these local partners, who, let’s be honest, are going to understand their own local markets and customers a lot better than we do.

This is really the core failure of many NGO projects: they don’t really consider the long-term incentives of the participants and recipients of their help. Of course, not relying on donations also allows DOT Glasses to scale much faster than other organizations, as the business model is sustainable and the revenues are reinvested into growing the footprint to help more people. The more we can sell, the faster we’ll grow. We just need to “prime the pump” with donations and/or social impact investment in the early stages in order to build out our first networks.

So you’re not a charity.

No. We have charitable intentions (and we’re a true social enterprise), but I also believe that it’s in a way disrespectful to people in economically challenged regions to assume that they are not motivated in the same way that people are in developed regions, by the opportunity to pursue success and prosperity with hard work. That’s why we believe end-users of our glasses should be paying for them, and the profits from that activity should benefit the local economies as much as possible. Ultimately, that is the way to help these regions develop.

Also, in many cases, charitable activities can have a detrimental impact in the area they’re trying to help. They may end up hurting developing economies, even though they have the best intentions at heart. Think of food charities that end up displacing local farmers who can’t compete with free stuff. That’s a real problem with charities, and one that is rather insidious.

Even sending volunteers to teach in slums can have negative consequences, because the local government starts to depend on the free handout (in this case, education) and doesn’t develop a properly functioning, stable educational infrastructure of its own. Which means they don’t care about creating their own teachers, and those few teachers that there are may actually have lower salaries because they’re competing against “free”.

With our work, we hope to create microbusinesses, with the help of microloans if necessary. We want to have entrepreneurial people start up their own eye care businesses. In the process, they create a better life for themselves and their families, but they’re also selling a new lease on life to those who can’t see well. And it’s been proven, that there is a tremendous increase in productivity when someone gets their poor vision corrected, which means additional wealth creation for individuals, families and communities. It’s a true virtuous cycle.

You spent a career as an executive in big corporations, as a consultant, and finally as an investor (including in StartupYard). What would you advise someone like yourself, who is thinking about a career shift toward charitable/entrepreneurial work?

It’s a great question. The road from the boardroom to developing DOT Glasses for remote regions of the world was a pretty long and winding one. But the fact that it was long and winding is important, as I learned new things from every role I ever had. Small things and big things. I became more well-rounded, and I could see the world from more angles.

I’m a huge believer in cross-pollination of ideas between industries, between companies, between countries, etc. For example, I brought a lot of my mobile operator experience to my role as CEO of a large alternative payments company, because both had a lot of B2B and B2C customers, both needed customer care, both needed direct sales, both were concerned about customer churn… and in some cases the mobile operator approach could be adapted to create a better solution for the payments company.

This isn’t a unique experience obviously, but the corporate world is set up against this to some extent. They want to hire people with experience from their own industry. But I went through a few different industries, as well as through consulting (which teaches you a lot about how to structure problems, organize projects, analyze data, and find the core essence of the analysis), and I started using that breadth of experience to mentor startups.

Startups (especially with young founders) often know a lot about their technology, their market dynamics and perhaps a few other select bits of information – but they often lack the big picture. They also often lack some key skill sets that they will need, such as sales, finance, and strategy, not to mention, they have no idea how to talk to the corporate world (although I admit I’m hugely generalizing).

So I help them with that. But perhaps even more important than providing some insights into missing skills, is providing cross-pollination. It’s all about identifying new opportunities (even new tangents) that aren’t obvious. It’s about synthesizing new value by bringing together entirely new elements. Which is what I did with DOT Glasses.

Coming back to part of your question though, the answer is to strive to become a cross-pollinator. Constantly learn new things, challenge yourself, get out of your comfort zone as often as possible, get out of your corporate bubble, and go out into the world and do things. Mentor startups, work in a charity, join a business club – but if you do it, do everything actively. Make an impact. Don’t be passive, because then it’s just a waste of time. I like to say that “life is too short to do just one thing”. I believe in side interests. I believe in planting lots of seeds and seeing what sprouts. And eventually one of those things can grow into something bigger and more beautiful than you could have imagined.

But don’t forget the lessons you learn in the corporate world about pursuing long-term economic interests, including your own?

Yeah, that’s right. Social impact work is not necessarily charity. We don’t just give, we also look for sustainable opportunities that can grow the overall economies we are focusing on. That in the end is a benefit to us, and to those regions. In my view, there are many, many activities that are currently approached with a “charity” mindset, that might be better served by a social impact, entrepreneurial mindset as well.

Hey, this isn’t rocket science here! We all know the saying: “give a man a fish and he eats for a day; teach a man to fish, and he’ll eat for a lifetime.” Well, it’s not just teaching is it? Make someone your business partner, no matter what it is they’re doing, and make it mutually beneficial, and that is going to create opportunities for you both.

How do you think corporate officers, like you were in the past, can better contribute to this kind of sustainable social impact?

Let’s say this: I think it comes down to really trying to understand, and develop a respect for the people you are trying to help. When I think about social impact, I think about not only looking at ways of improving someone’s life, but also improving my own, and the lives of those around that person. That comes back to you, in the end. There is a part of social impact that should be “selfish,” in a way. I am doing this because I want to live in a better world, for me as well as for you.

I think it is a danger among those of us who enjoy some material success, that we begin to imagine that we are giving and no longer taking anything. However in most charitable activities that just isn’t true. We are taking a lot, in terms of what matters to us: respect, reputation, the feeling of doing good works. That is something of value. You should always be aware of what motivates you to do what you do.

Again, nothing wrong with feeling good for giving back. But I would encourage people to go further than that, and to think about how their actions really tie back into their own lives. This is how we empathize with people in the real world.

If I am helping someone in a remote village in India to see better, then how is this affecting my own life? I can tell you, it does affect my life. Leaving aside that each individual with the proper tools in life has a chance to change the world, to be the next Einstein, I am also helping to make sure that this person is being economically productive.

If people are more economically productive, it is more likely that they will be prosperous, and so will need less support in other ways. Eventually, developing regions become developed, and I can enjoy the benefits of that development in my own life. That is a prosperous cycle, and if you don’t actively look to see it, I think you lose sight of why you’re doing what you do. You may end up not really respecting the people you’re trying to help.

What have you learned from this that you didn’t already know? What has surprised you?

I’m an inventor at heart. I have lots of ideas. But I have learned something really new in the process of moving this project past “idea” stage, and into realization.

What I discovered is that the true “innovations” that end up happening are not only around the idea itself, but rather the things you have to invent in order to get that idea to work. What I mean is, the “solutions around the solution,” are actually where a great deal of the creative work happens.

So I start out with the lightning strike about “good enough vision” which creates a transformative lens concept. But to realize the potential of the lens concept, I had to work very, very hard to develop one-size-fits-all modular glasses (only my 3rd industrial designer cracked the nut – the first two didn’t find a solution), because I realized that the combination of those two elements could be the magic bullet to solve a vexing problem that no one else had managed to solve.

But after I had the glasses, I realized I needed some tools to facilitate the streamlined process I was imagining, so I had to design a vision tester and a pupil distance measuring tool. And then to bundle all that together into one “kit”, and designing an end-to-end process around that kit in order to get the glasses to those people that needed them… it was one problem after another that had to be addressed.

Each step required an innovation, but the innovations built on each other. Would someone have designed my pupil distance measuring tool without my modular glasses? No. But they were required for the entirely new ecosystem that I was building. So building the entire ecosystem took much more time than I expected.

So in the end, the work is more creative than the ideation.

Yep. It is. That’s something you can’t know until you try. I’m happy to have found that out, because being really creative and solving real problems every day is how I like to live my life.

If you’re interested in contributing to the DOT Glasses project, you can do so today by clicking below and pledging to their crowdfunding campaign:

Michal Kratochvil: Budgetbakers CEO Talks Profitability and Pivots

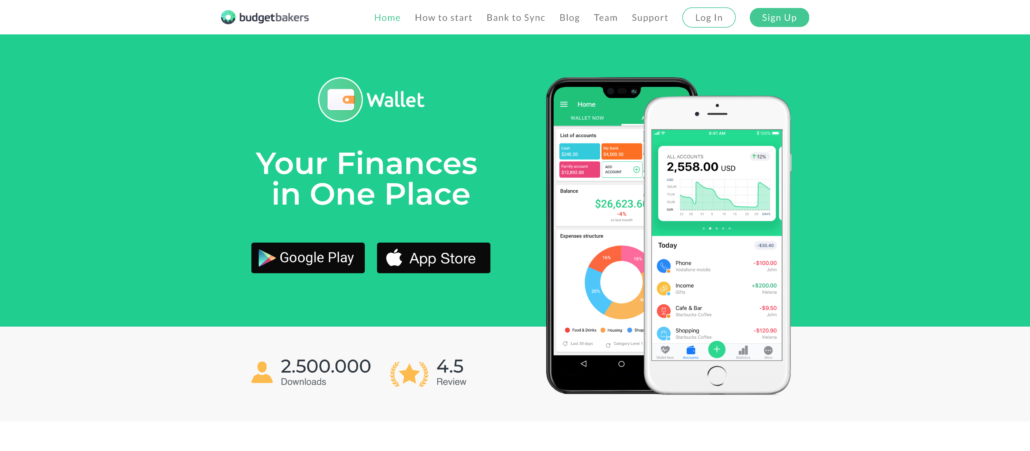

/in Interviews, StartupYard News/by StartupYardMichal Kratochvil is a StartupYard investor, former head of Accenture Consulting for Central Europe, and currently the CEO of StartupYard Alum and popular personal finance management platform BudgetBakers (SY Batch 5), a role he took up in 2016.

BudgetBakers informed investors this month that they are now cash flow positive and, in fact, that monthly revenues had nearly doubled in just a few months, after 2 years of mostly steady growth. This news came just months after BudgetBakers nearly halved the size of its team, and pivoted to focus developing some the flagship app’s core features (like integrations with banks).

I sat down with Michal to talk about the last 6 months at the company, and what he’s learned from the ups and downs of running a tech startup for over 2 years. Here is what he had to say:

Hi Michal, so you’ve been with BudgetBakers for over 2 years now. What were the surprises? If you could go back to the beginning, what would you do differently?

Michal Kratochvil, CEO at BudgetBakers since 2016

I should say I did everything perfectly, and everything went according to our brilliant plan, right? :laughs: Ok, there are always going to be things you would want to change because you know the outcome, but this is cheating. If you’re asking how I would have changed our general approach, there are a few things I would do differently. I would try and make some of the “surprises” less surprising.

How would you do that?

Let’s be concrete. When I joined BudgetBakers, Founder Jan Muller and I explored many options as to where we could take the company. I spent a few months getting to know all the possibilities, and coming up with plans.

We decided to focus on a couple of core activities. One of them: continuing to develop our B2C product, which was already enjoying a lot of popularity, with tens of thousands of active users (it was then in Version 2, we are now up to Version 6). Today we have added tens of thousands more, and recurring revenues have grown from nearly zero, to tens of thousands of Euros per month.

The other activity was to explore the second pillar of our business, which I believed was going to be our partnerships with financial institutions, particularly banks. There are a lot of opportunities for personal finance management software companies to help banks and their customers. Banks are very much in need of new ideas and new ways to serve their customers, and we have a personal finance product that people choose to pay for. So I think we have a lot to offer, either as a white label, or in some other form of partnership.

Of course, working with a bank is a difficult process, and matching up and actually managing to make a deal at the end of the day is very tough. They have dozens of priorities, you have just a few.

What I think is interesting is that my advice about the former (B2C), and my advice about the latter (B2B) will slightly conflict. I believe now that we had to be more patient when it came to developing our B2C product, particularly in our release schedule, and I believe we should have been less patient in our B2B activities with partners.

Why more patient with the B2C product?

You know, I think it comes down to just human nature. We keep making the same mistakes, because we don’t really change that much as people. We are startup guys. We want action! Get the products out the door.

When I joined the company, I saw that our dependence on platforms like Google Playstore and iOS App store was a vulnerability. You are getting most of your business directly from these places as an app maker.

What I did not expect, which I found out quickly, was that your fortunes can really hinge on these platforms on a day to day basis. When we went from, I think v2.x to v3.0, it was a major shock to me how violent the reaction was from the user base. Instantly, your rating drops from average 4.5 stars, to under 4. Closer to 3. Then slowly, over months, it starts to go back up as you fix some of the things you got wrong, and customers sort of get used to some of the changes.

BudgetBakers provides a complete personal finance solution for individuals, families and small business.

Why does this happen?

Please, if I knew why, then it wouldn’t happen. :laughs: I think people just do not like change. When we make major changes to the apps, even when we have to make them and the long-term results will be better for the users, still nobody likes change. You moved that one button, you disrupted my flow in the app, so I’m pissed. One star. That’s what happens.

Not to mention, there are bugs that appear when you make major releases. This also provokes a harsh reaction, especially from your biggest fans.

So how would you try to be better at this?

What I would do differently, which frankly I have still not gotten 100% right, is to make us a bit more patient with the release of a big new version, and try and take the release in smaller steps. Try to create more of a transition in the product from one version to another, and game out more of the steps needed to get from here to there.

You need a bunch of things to work really well in order to push a major release. You need to migrate data and settings, you need to create a path for the users to move from the old UI to the new UI, and still be comfortable with the product.

We do testing, and we try to get everything working, but if I’m being honest, the temptation is always to push too fast, and to get the release out before it is really ready. I am saying this, knowing that we will still want to move too fast in this regard.

Do you think you will ever get the timing exactly right? This is a problem even for huge software companies.

I think it will never be totally right, but it can definitely be better. What you do not want is this sudden shock reaction from your userbase, who are suddenly giving you one-star reviews because of what is really a dumb mistake, or a series of small errors that can be avoided.

As you grow in maturity as a company, you have to get better at this, because your customer base is growing also. It is starting to include people who do not have patience for these kinds of issues. They don’t know the history of the product, and their level of engagement is not as deep. You can become really invested in big changes to the product, and then fail to explain these changes well or to justify them to the users. Then you have problems.

We are no longer in the land of early adopters at BudgetBakers. Our hardcore, long time users, while they are still really important to the way we think about the product, and test the product, are not the average user anymore. They become increasingly the edge case, and this means you need to be casting new hooks and talking to less engaged customers as well.

I would say our power users are 20% of our paying customer base. So the 80% are the silent majority, and these are the people who you need to aware can very quickly change their mind about you. These are also the people who will not tell you what they need. You have to really dig in to understand them. They won’t spell it out for you.

Your 20% might be very vocal about changes, but they will not walk away either. What they tell you is important to them, may be important, or it might not be. The more casual users, who are seeing you in a less personal way, can be less forgiving. If you don’t give what they need, they go elsewhere.

Part of growing your product maturity is to understand that your customers’ actions are more important than their words. If people complain, and yet we can see that they are using the product, maybe even using it more, then we should take this under consideration. Everyone likes to complain about changes.

[Author’s note: at the time of writing, the current rating for BudgetBakers’ flagship app, based on nearly 89,000 reviews, was 4.5 Stars on the Google Play Store]

One of the biggest mistakes you can make is to deprecate a popular feature without a real replacement.

Yes! That is a huge danger. Worse if you really don’t appreciate how important something is until you take it away from your average users. That can be surprising. Every time we do a big change, it does surprise me, even though I know now to expect this.

Just spending a little more time on something and getting beyond “it works, get it out the door now,” is what we have to work on. Just sleep on it, and play with it for a little longer. 3 weeks more of testing. I keep saying this, but every time the temptation is the same, to rush the release. You want those new features to be out in people’s hands, and you want that feedback.

It’s a bit of an addiction, maybe. We can’t stop the cycle. It’s like the binge and the hangover. You load so many things into the big release, and then you deal with the hangover, which is negative feedback, complaints, etc. You feel that all the way down your funnel, for weeks and months.

In Node5 where we work, as you’ve seen yourself, there is a sign about “the better is the enemy of the good.” This is it. We always want to be better, but sometimes you just have to be good.

Mentor, Investor, Startup CEO: Michal Kratochvil talks about life at StartupYard

StartupYard investor, mentor, and CEO of StartupYard alum BudgetBakers, Michal Kratochvil joined the world of startups after a career in corporations as Managing Director of Accenture Consulting in Prague. Michal gives us an idea of how working with startups has changed his view of business in the past few years, and how he became a believer in Acceleration.

Posted by StartupYard on Monday, January 15, 2018

In 2017, Michal spoke on video about his experiences as a StartupYard investor, mentor, and CEO.

So be more patient with your release schedule. What about being less patient with your partners?

Let’s say not “less patient,” because you have to be persistent in this business. Instead, let’s say: “more opportunistic,” or “less confident,” about the likelihood of any one deal working out.

A big danger for any small company, particularly just after raising a seed investment as we did, is that you commit too many of your resources to one deal. You can spend a lot of money and effort working on this one deal, and if it falls through, for whatever reason, this is money that is not coming back.

This can be just bad luck. A deal can fail to happen because somebody changes positions, or gets fired. That happened with us. The deal we hoped would happen just didn’t. It not in our control, nor in theirs. It just didn’t happen.

So if I had this to do again, I would remind myself that you need to be constantly building up your pipeline of opportunities. You can’t stop building a pipeline, because when you stop, you inevitably become increasingly dependant on what others decide to do. Basically, more dependent on chance and luck, because you aren’t making the opportunities actively.

When you are working towards one particular deal, you get focused on the value this deal can provide for the company. However, that deal is worth nothing until it is signed. Until it is signed, you need to be constantly working on alternatives in your pipeline. That is a best-case scenario, which is that you have to tell partners, “sorry, we made another deal.”

You know, going back to someone who you dropped 6 months ago means you start the process all over again. You can’t afford to do that. They can move on in that time. You are basically starting at zero, so you need to be building that pipeline until the moment you make a deal.

Do you have a new appreciation for the role of luck in this process?

Yes, in a way. Of course luck doesn’t matter if you don’t do the work. We did well by really investing in our technology and building up our products from the ground up. We did the work. At the same time, this work in the case of this particular partner, didn’t pay off. It was bad luck.

That being said, this same hard work can pay off in ways you don’t expect at first. When this deal fell through, for example, we had to make a really hard pivot to focusing on growing our B2C product faster, and adding more features that we were very sure would attract more customers.

As a result, we sat around really asking ourselves: what can we do in a matter of days or weeks to increase the sales of this product? That led to some big changes, and as we’ve seen, some dramatic results in the end. Our revenues basically doubled in a few months.

We absolutely could not have done this if we had not been investing well in the development of our backend. We would not have had this resiliency that we had, and the pivot would not have worked without that.

Still, and again, there was an element of luck here as well, in that in the moment we turned away from the B2B business, there was a new opportunity in the B2C space that was just opening up. I’m talking specifically about the ability to connect our user’s accounts directly with their banks, so that they can get a view of their finances without doing any manual data entries. This was the perfect moment to really focus on that functionality, and as a result we made a deal very quickly with a big data provider to connect with two or three times more banks than we had before.

What have been the hardest moments in the transition to a cash-positive operation?

When we had to make this particular pivot, we had built our team with the hope that we would make this B2B deal. When it didn’t happen, we had to change the team. Letting people go and shrinking the team has been very tough on us. No easy way to say it. It is not fun.

I have plenty of experience with this, but quite honestly, it is not something you want to get used to. It is not nice, and it does hurt.

You don’t have to talk about that…

Well, it is fresh, but also there are some things I think we can learn from it. We can do better, always. I want to be clear first of all that I still believe in each individual that we had to let go. This was not about them, but about where we needed to be as a company. That is important to emphasize for me: it was never a mistake to work with any of them. If I could keep them all, I would.

Have you learned something you didn’t know about building a team?

Yes, I always believed that you need to consider several things when hiring someone. First: you need to consider the immediate goals of the company, and the talent you need for those. Then you need to consider the long-term health of the company, and just as importantly, you must always consider the personal development of the people you hire.

I believe strongly in this, that you must invest in people when they join your team, and also in the case that they may choose to leave, or you are forced to let them go. Still, I believe we owe it to people who we hire to see that they land in the right place. I’ve put a lot of effort into making sure that these people have their next steps and are secure. That’s something I believe we promised them from the beginning, and you must keep your promises.

I’ve been managing people for 25 years. There are those managers who keep their promises and commitments, and those who don’t. If you do keep commitments, and if you are focused on the good of your employees during and after their time with you, then you are going to have a better time in life, and an easier time finding people to work with you.

But hiring for a startup is different than hiring for a big company…

Yeah, because the promise is a bit different. You are building this little family, and you’re asking people to be more flexible, and find their role in the company over time, instead of having that pre-defined by an HR department or something.

That means to me that I have asked people to have faith in me and the company, and I have put faith in them as individuals. I could not sleep at night if I did not believe I was doing all I can to help those who have helped us. That is a core commitment that you make to people as a leader. You must follow it through.