Anand Giridharadas: Winners Take All : The Most Important Book on Tech in 10 Years

We don’t post book reviews often on this blog. Sometimes we recommend books we think our startups should read. We have a reading list, which deserves an update as well. More often we talk about books with our startups in person, and many that the management team recommend are standard fare for startups and business. Dale Carnegie, Al Ries, and business classics like Zero to One, Crossing the Chasm, or books and articles by Malcolm Gladwell.

This post is a bit different, because the critical consensus on Anand Giridharadas’s new book Winners Take All : The Elite Charade of Changing the World, has not yet been formed. Still Giridharadas’s well known views, first as a columnist for the New York Times, and then as a member of the speaker circuit he himself criticizes in his new book, are rare harsh words from a tech industry insider who knows of what he speaks better than most.

In truth, the book is a kind of validation for us as well. StartupYard has been publicly critical of “Thought Leadership,” and the incestuousness of the idea space that tech startups and corporations tend to occupy. We have been publicly in favor of many of the solutions that Giridharadas suggests, including Universal Basic Income. Still, his book comes as something of a wake up call for our industry. One that should not surprise anyone, but probably will.

“Making The World a Better Place”

When we refocused StartupYard 5 years ago on global projects with an emphasis on novel technologies, part of our thesis was that it would not be enough for us to “make the world a better place.” This is not least because “making the world a better place,” often functions as an excuse for failing to take on important, and yet smaller issues. Instead, we focused on developing the ecosystems in which we live and work, be they the city of Prague (in multiple cooperative hackathons with the city, and by investing in local startups), the Czech Republic, CEE, or finally, the globe. We also live on the globe.

We also tried to focus on problems with a deep impact on the world that could be widely felt. That led to our investments in companies like Gjirafa, Neuron Soundware, OptioAI, Rossum, or TurtleRover. Each of these companies does more than simply allow large companies to increase profit margins. They create new markets and new ways of looking at old problems. They create opportunities for small actors who can’t afford to compete with the bigger players. They drive competition, not individual competitiveness.

What we tried hard not to do was to choose startups and make investments solely based on the idea that these companies might be financially successful. Moreover, would their impact on real people’s lives be meaningful, measurable, and tangible, ultimately, to the founders and to us?

That might sound like “Making the World a Better Place,” but it’s not the same thing. To develop and push the world towards a more just, more fair, and more prosperous future is not to simply “make the world a better place.” In fact, it should not surprise the reader that new technologies can make the world a harder place to live in. These are issues that we must face as moral actors in the world. Thus: will the automation, or new ways of working and living our startups are trying to invent, make the lives of the individuals it is most important to, better in a meaningful way to them?

When we talk about a better world, we often just mean a better world for us. One in which we feel better about ourselves. Yet, this is not enough to help a person sleep at night. At least not to help this investor sleep at night.

Giridharadas gives shape to these thoughts in his book. He asks us: who suffers so that we may succeed? These are the people to whom a debt is truly owed, no matter who they are. Our responsibility to the world around us does not end with the interests of our shareholders. It extends to all who our technologies touch, directly or indirectly. It extends to promoting a moral worldview to the founders we work with – one in which greed is not good. Giridharadas also asks something more: what happens when success does come? What will we do when and if we do win?

Facing Win-Lose Scenarios

One of the themes of Winners Take All, is pointing out and challenging the insidious idea that any technology company can do essentially anything it wants to do, and still one can find “win-win” scenarios, in which the impact of their choices can be seen as positive for everyone involved. It’s ok that Uber destroys the taxi industry, because the net impact will be good. It’s ok that Airbnb might raise property prices, because in the long run, it will all balance out. Having personally met with and heard talks from executives at these companies, along with many other major tech players, I can assure you that they do not have a concrete view of how this balancing act will work

In tech, most do not take responsibility for this balancing out. We disrupt, but we don’t fix the problems we create.

Worst of all, investors and startups may justify their negative impacts on the world around them by spending the money they earn on fixing the very problems they created, via charities, or via yet new startup businesses. This can be like treating a hangover with more alcohol. It tends to lead to similar results. New approaches are needed.

Thus tech companies can disrupt and invalidate systems that employ and support large numbers of people, and they can justify this disruption by pointing to a possible future in which their impact will be seen as positive by those who suffer today. Often the worldview is passed down from the investor, to the startup, to the individual team member: “it doesn’t matter if we wreck a few lives… eventually they’ll thank us for it.”

This is not good enough. That is why StartupYard is in favor of Universal Basic Income research, among other governmental and regulatory approaches to protecting individuals, classes of people, and regions from the negative effects of the very innovation we invest in. We simply will not profit from a world that we are destroying. That’s also why we have consistently criticized governmental approaches to innovation that idealize the tech industry as a cure-all for social and economic inequality. We can do many things, but we cannot replace democratic institutions, or be the voice of unheard people.

Sometimes winners win, and losers lose. In a just world, and in a world we do want to live in, the losers don’t have far to fall. Losing is, after all, what almost all of us have to do at some point before winning. The waste and the pity of a winner take all world is that so many great things come from those who have lost something before – people who fail know the value of succeeding.

Survivorship Bias – The Nose Goes

Finally Giridharadas asks important and difficult questions about what it means to actually be a winner. Can we ever know, if we do succeed, that this success is due more to our abilities and our hard work, than to luck, or to the simple fact of who we are?

He reminds us of something that is also part of StartupYard’s DNA: the belief that someone’s CV is not their life. In our business, it is easy and in some ways much simpler to follow the signals of success that follow certain people through their lives. Did the person go to Harvard? Did they have a good position in a previous company? Did their past startup succeed?

We focus very little on these details, because they don’t tell us that much about people. There are plenty of idiots in C-level positions. There are plenty of bad founders from Yale or Oxford. Hard experience has shown us that a person’s CV doesn’t always have a strong relationship with their individual potential when it comes to founding and building a company. If we were to only look at Ivy Leaguers from prestigious tech companies as founders, we’d miss people who have no such credentials, but have far more important qualifications than that. Qualifications like knowing their customers better than anyone else. Like being more devoted to what they do than anyone else in the world.

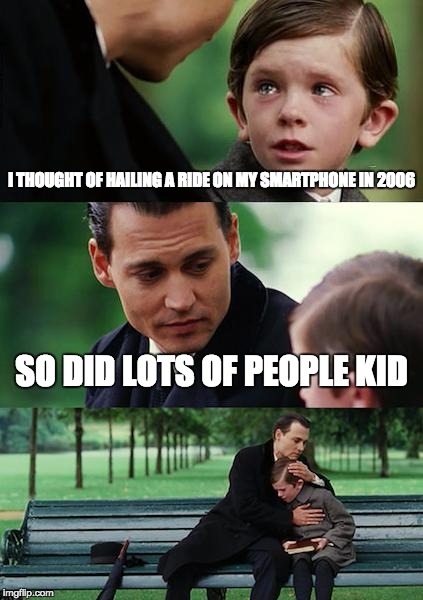

What is interesting about the culture of startups is that we “celebrate failures,” but actually we celebrate learning from mistakes. True failures, like not working hard enough, not getting good enough marks in school, or failing to even act on an idea you had in the past, are not celebrated this way, because we don’t tend to learn from them. A story of real failure is not interesting, because it doesn’t have a happy ending. It just ends. Somebody who failed at 25 is inspiring. Somebody still failing at 50 is pathetic. We celebrate people who almost succeed, and probably will succeed in the future. That isn’t the same as failing.

The heuristics you use for making decisions about people should be based on your own experiences, and not those of others. This is what we call “instinct,” which for some reason has become taboo in the technology world, where everything is data and metrics driven. We believe in following your nose. Your nose tells you things your eyes and ears will never quantify.

Read the Book

Enough of my opinion on the topic. Read the book! I promise you’ll at least learn something you probably didn’t know before.