Create the Perfect Elevator Pitch

/in Marketing, Starting a Business, Startup Tools, Startups/by StartupYard10 Questions to Ask a Startup Accelerator

/in Life at an Accelerator, Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYardThe StartupYard Big Book of Marketing

/in Marketing, Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYardThe StartupYard Big Book of Pitching

/in Marketing, Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYard2 Mental Tricks That Will Make You a Better Entrepreneur

/in Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYardThis week at StartupYard, our current batch of companies has been in the tall weeds trying to finalize their marketing and messaging for our press launch, which went off last week.

The cliché expression for the feeling they are experiencing is “jumping off a cliff and building your wings on the way down.” A version of that quote is often attributed to Reid Hoffman, who uses it to describe entrepreneurship generally. In fact, the quote originated with the science fiction author Ray Bradbury, in a review of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C.

In a way that makes much more sense. The quote describes inventiveness and forced creativity. It can be the realm of the entrepreneur, but it is more generally the realm of anyone creative.

The reason I mention this is that a founder can be both very strong in creativity, and still very unconfident in their ability to creatively communicate with customers. That’s what my job with them is all about.

Creativity and Empathy

This week I’ve done two workshops with our startups. One on “Storytelling,” and the other on “Customer Personas.”

To me these are essentially the same topic. Stories are the way that the human mind invents and creates the future, and how we understand our past. It is about how every “character,” or person undergoes an arc, and how those arcs interact and impact each other. Building personas, in the way I see it, is how we examine our assumptions about people, formulate tests of our insights, and discover ways to empathize with and understand those who use our products.

Here we’re going to talk about some simple mental tools that are going to help you ideate and test your own assumptions about your customers, in order to better serve and sell to those who need your products most. In many ways these will not be unfamiliar concepts, but to the mind of an engineer or a maker, they are often mysterious and elusive in terms of application, particularly when it comes to marketing.

I’ve written a number of posts on this topic, so I encourage you to start with these. Go on, I’ll wait.

…

Double Loop Learning

Double loop learning is a basic model for creative and flexible thinking. In essence, it suggests that there are two ways to approach the learning process (such as in product development), a “single loop,” or a “double loop” process.

Here is how they look:

In the Single Loop Thinking:, you begin with assumptions (a mental model), logically leading to a set of rules, which lead to a decision. From there, you adjust your decision based on feedback.

In Double Loop Thinking: You do the single loop, but at the same time, you go back to the initial assumptions and adjust the mental model, which may cause you to adjust the rules, and not just the final decision.

Example of Single Loop: In deciding on buying a car, I imagine the car I want to buy: Color, Type, Make, Model. Using this model, I decide which dealership to go to, and how much I can expect to spend (making rules). Based on this, I decide on a dealership. Now I go to the dealership, and I find out if I can get the deal I want for the car I want. If I can’t find the car, I go to another dealership (information feedback to decision).

Example of Double Loop: I do all of the above. But I also ask myself: should I be trying to buy this type of car? Were my ideas realistic? Based on what I learned from my visit to the dealer, what other cars got my interest, and might be better for me? I adjust my expectations, and make a new decision about the kind of dealer I need.

Why it Works:

Single loop is in fact the way we are taught to learn in school. We are given rules, and told to apply them continuously, looking for the correct decision given the stated rules. Just think of all that math homework you had to do.

That kind of singular repetitive learning works most of the time, particularly when a desired outcome is pre-determined. However, this can also lead people to forget that the initial mental model may be flawed, particularly after gaining real experience with it.

The most typical case in startups, is the startup that makes some early decisions about who the customers were and what they wanted, but never came back to those assumptions, and ends up serving a smaller niche than necessary, because all their later decisions are based on data they’ve gathered so far. The longer a company remains in this “single loop,” the less likely they are to challenge their original assumptions and thus be able to successfully pivot to a new market.

Here is a concrete example using a classic business case many people face even as kids:

Single Loop:

1. I decide to sell lemonade. I choose a location for my lemonade stand and a price for the lemonade, based on my intuition about what people will pay.

2. I observe the sales cycle. How many people visit, and how many people convert to buying a lemonade.

3. I slightly adjust prices and location to optimize my sales.

4. Go to 2.

Double Loop:

- I decide on a location for my lemonade stand and a price for the lemonade based on my intuition.

- I observe the sales cycle.

- I slightly adjust prices and location to optimize my sales.

- I re-examine my initial strategy, and try a new location, or even a new product (maybe ice cream?)

- Go to 2.

The OODA Loop

Ok, maybe running a startup isn’t exactly like flying a combat mission in a $50m fighter jet in the U.S. Airforce. Still, you can learn from the mental training that fighter pilots, spies, and military strategists use on a continuous basis – often minute to minute.

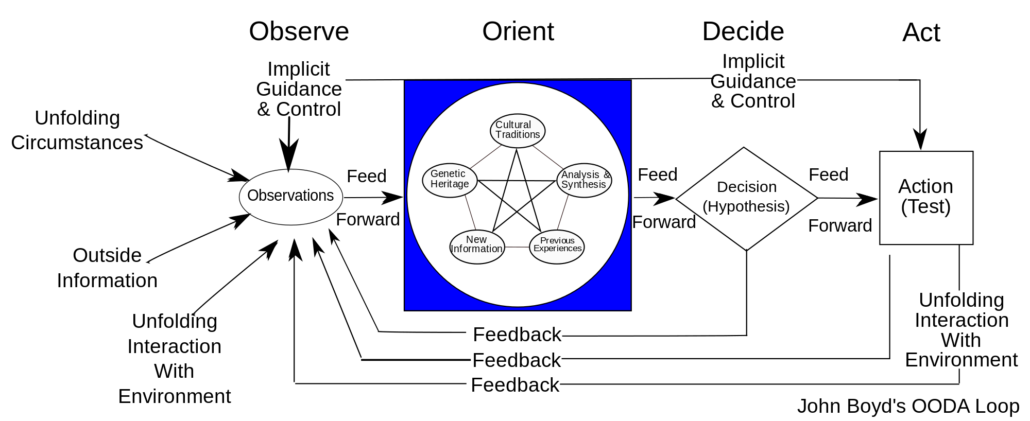

It’s called the “OODA Loop,” for Observe Orient Decide Act, invented by Air Force strategist John Boyd, called by some “the greatest military thinker no one ever heard of.” Here is a very thorough explanation of the general philosophy behind it, written for a popular audience. In as simple terms as possible, the OODA Loop is a mental tool which forces its user to continually adjust their future expectations, based on current realities.

Why it Works:

The OODA loop is a tool for forcing oneself to continually affirm their past decisions using current information, and to drop previous assumptions and goals based on current circumstances. The OODA loop is used as a mental tool to keep you focused on the current moment, and what is happening around you, to avoid sticking to a strategy which is not working, and to continually notice new opportunities.

Boyd’s central thesis has become a core principle of modern warfare, and a frequently used technique in sales training, and even by professional chess players. The core tenet is this: the mental models one holds tend to lose their usefulness in chaotic situations. Therefore, updating our mental models, or “orienting” our expectations can help us to make better decisions for any given situation.

What does that look like practically? I’ll refer to a thought experiment that Boyd himself proposed:

“Imagine that you are on a ski slope with other skiers…that you are in Florida riding in an outboard motorboat, maybe even towing water-skiers. Imagine that you are riding a bicycle on a nice spring day. Imagine that you are a parent taking your son to a department store and that you notice he is fascinated by the toy tractors or tanks with rubber caterpillar treads.”

Now imagine that you pull the skis off but you are still on the ski slope. Imagine also that you remove the outboard motor from the motorboat, and you are no longer in Florida. And from the bicycle you remove the handle-bar and discard the rest of the bike. Finally, you take off the rubber treads from the toy tractor or tanks. This leaves only the following separate pieces: skis, outboard motor, handlebars and rubber treads.”

The thought experiment then asks us to orient to this new situation by putting all the elements together, not in reference to how they were introduced, but rather only focusing on what the elements themselves are, or can be.

You are on a ski slope. You have skis, you have a motor, you have handlebars, and you have rubber treads. What’s going on?

Spoiler: You’re on a snowmobile. That’s what’s happening. Nothing you learned to this point other than those facts matters. To master the OODA loop, you have to be able to clear your mind of these details when they are no longer useful.

The OODA loop focuses on observing the current situation, combining that data with experience and knowledge, and making a decision focused on what is happening right now.

Actually we are quite familiar with elements of the OODA loop in pop culture. Films like The Bourne Identity, or the recent Bond films show classic outcomes of the use of OODA loop, which is the result of real special operations personnel training the actors and consulting on the scripts and fight scenes.

The tension that arrises from these films, in which we observe someone using the OODA loop, comes from the audience being slower to understand how the protagonists are processing situations. As an audience, we have a hard time dismissing details and living in the moment, so it is exciting to see characters who are unpredictable, and yet acting very logically.

This scene from The Bourne Identity is a classic example of the OODA loop in action.

Here’s another from the classic film Top Gun, handily labeled so you can follow the steps that the fighter pilots are using. This video has an added bonus in that Maverick, played by Tom Cruise, fails to use the OODA loop, and suffers the consequences.

The Monty Hall problem

The OODA loop is a practical tool in decision theory. Probably the most famous case of a practical application is the so-called “Monty Hall Problem.”

The problem was first articulated in the 1970s in response to an American game show called “Let’s Make a Deal.” The problem goes like this:

“Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?”

What’s important here is differentiating between a decision strategy, and a single decision. While the chances of the original choice being correct are indeed ½, the odds that the initial choice would be correct over many iterations are only ⅓. That means that if you consistently stick to your choice, you will only win ⅓ of the time, whereas switching will give you a win ⅔ of the time.

Why?

Think of the problem again, but with different numbers. Suppose there are 100 doors. 99 with goats, and 1 without. Now suppose you picked a door, and the host them revealed to you all 98 other doors with goats behind them. Now do you switch your choice? Whereas your initial choice had a 1/100 probability of success, your new choice, has a much higher probability. This time it’s 99/1.

If you don’t believe me, you can actually test the phenomenon here.

Applying the OODA Loop

Now that we see the difference between decision theory and probability, we can begin to understand better how the OODA loop works. Because it requires that we observe according to the latest data, we begin to see that applying decision theory in real life becomes more practical.

Take this situation:

You walk into a bar, and observe a group of large men in military outfits standing at the bar. The men are sweating profusely and breathing heavily. No one speaks. You see that all of them are carrying rifles or pistols. They appear not to notice you.

Your observation moves to orientation: your judgement says there is probably trouble. Based on the available data, you decide that turning and walking out will draw attention and cause them to panic, or even attack you. Challenging them is too dangerous, as you are alone and unarmed. You decide to continue past them to the bathroom, where you know there is probably an exit.

You get out of harm’s way and look and listen from safety. The men stand quietly. Eventually a bartender appears and they order beer. The men begin to laugh, and one of them explains to the bartender that they are just coming back from a game of airsoft.

Orientation Leads to Better Decisions

Notice first of all that observation and orientation happen always before a decision is made, or an action taken. The decision is then subjected to another round of observation, where the first set of data are taken together with the new set.

We see from this example that quick reactions are, over the long run, less important than correct decisions. Anyone who has been trained to drive a car in mountainous areas has probably been told that the best decision when a deer runs across the road in front of you is to hit the brakes, but not to turn. This is not because turning is unlikely to help you avoid the deer, but rather because swerving away *is* more likely to cause you to crash the car (possibly into another car).

Those with relevant experience know that the deer will mostly likely run away if you slow down but don’t turn. If you turn, the deer can become confused and may hold still, causing you to hit him anyway. Even if you hit the deer front on, this is less likely to endanger your life than a side collision or losing control of the car. Either way, your best decision is not to turn: no reaction is better than an overreaction.

If in the former example of the OODA loop in the bar, you had reacted as quickly as possible to the situation, you would have made mistakes. First of all, you would have suddenly run out of a bar that was perfectly safe. Or worse, you might have attacked a group of men who were armed.

If you had challenged the men, you might have been killed, or beaten. If you had run out, you might then have called the police, causing further trouble, and perhaps even unneeded violence. If you think that’s overselling it, keep in mind that police shoot civilians with distressing regularity, in some countries, for such offenses as holding a mobile phone, or a toy gun. That often occurs because the police are not trained properly – such as with the OODA loop. Your effective use of the OODA loop could prevent that from happening.

Thus, in this situation, a slow reaction was preferable to a fast one, which is why you made a conscious decision to continue to the bathroom, rather than to engage with a situation you didn’t understand yet. You then moved back to observation and orientation. Discovering that the men are just coming back from a game, you may decide that no further action is necessary. If the new situation, by itself, does not appear dangerous, you may then decide to dismiss your concern, or you may decide to continue to observe.

OODA for Entrepreneurs

As Malcolm Gladwell points out in his book Blink, which explores decision loops in human interactions and business, as well as in historical conflicts, an ability to continually orient to one’s current circumstances is the greatest predictor of failure or success- a predictor more powerful than numerical data or objective observations.

Consider how this can be applied in the thinking of a small business. In the fact of numerical advantages, or sudden threats (such as bad PR, or even a troll on twitter), to what degree is your decision making purposeful, and designed to accomplish a known goal? Are you capable of altering your strategy to take advantage of new information and new events?

Observing new facts is easy to do. But consciously challenging an existing mental model is much harder. Reacting to data only after deciding *how* to react, can make the difference between a major gaffe, and a well-handled situation. Those who are able to act according to the most relevant information in any given moment are likely to win in the long run. Just as in picking stocks, or playing poker, success is found in not allowing your initial strategy alone to determine your future actions.

As John Boyd himself put it, to paraphrase: “in any game, the winner is most likely the one that can orient to new developments and alter their decision making as a result.”

StartupYard is Accepting Applications for Batch X: Automation, Blockchain, and the Future of Work.

This will Make You Think Again About Accelerators

/in Life at an Accelerator, Starting a Business/by StartupYardIs The Startup Pitch Session Dead?

/in Starting a Business/by StartupYardAs the most recent startup conference season has gotten rolling, I’ve been on the road to different cities in the CEE region. Warsaw, Kiev, Budapest, and soon Gdansk and Vilnius among others.

Certainly there are more startup conferences than there ever were in the past, so we’ve become increasingly choosy about which ones we attend. Today to evaluate a conference opportunity, we ask first “will they let us speak and present StartupYard,” and second “will we get 1 to 1 time with startup founders?”

The Best Startup Conferences Aren’t Tradeshows Anymore

I must say this is somewhat a reversal from the days when I first attended tech conferences. It used to be all about the pitch sessions. The whole event would be organized around a few keynotes at different stages, and a series of pitches, often with a big prize to draw startups and a crowd. That is the experience at places like Slush and Disrupt, as well as the former LeWeb.

We’ve written before about how useless this carnival approach can be for many who try to make real connections and tangible progress at such events. The light show outshines the personal connections, unless you are the type of person who can work a room full of strangers like a pro networker. You’re probably not. Natural social butterflies are rare in this business.

The most shiney startups would pitch, and then I assume they’d be bombarded with interest from investors who compete for their attention, rather than the other way around. This system had its obvious problems, but the worst was that it gave many startups the impression that they were shopping for the best offer from investors, rather than looking for a real match with the right investor.

My personal disgust with this dynamic culminated with an investor keynote in which a particular VC, who will go unnamed, patronizingly explained to startups that they need to “be the hot chick at the party,” for investors, and “play hard to get,” and assorted other bogus mind games that make founders impossible to deal with. Sexist and gross, of course, but also counterproductive and boring.

Obviously this is self serving, but StartupYard simply does not compete on the size of our investments, and we don’t want to talk to the “hot chick,” we want to find the company with the best team who want to make a real global impact. For a long time that kind of investor and startup attitude made conferences less than effective in helping us to scout and make relationships with startups that could fit well into our program.

The Pitch is Dead: The Conversation is Back

So I say with some relief and hope for the future, that it does appear that the up and coming startup focused events around CEE, the ones not burdened with heavy price tags and expensive catering, are doing away largely with the pitch competition format. Big ticket events focused on the public, corporate executives, and big speakers are still around, but happily startups are gravitating to more personal events where they can have time to really talk to people.

At Wolves Summit in Warsaw just last week, there was a pitch stage, but there were only around 50 seats, and I didn’t attend a single pitch session.

I was too busy taking great meetings with relevant startups, arranged in advance with intuitive software, and held in 4 different halls with a stunning 120 tables in total; most of them occupied. Interestingly too, at Wolves there is effectively no main stage, and consequently no temptation by the organizers to book big headlining speakers– a decision that inevitably leads to higher prices, more tech/startup tourists, and less time for startups to meet with each other and with investors.

When Wolves got started in Warsaw, the event was a pitching event. It was held in 4 screening rooms, and mentors were in fact pitching judges. As a result, very little personal interaction could happen because people were too busy with the pitching. The event has steadily improved with the focus on personal interaction.

Conferences that have built their reputations on speakers who charge €25,000 or more to talk about their salad days at Apple, or as VC investors, early Google employees, or startup founders, have becoming increasingly irrelevant for early stage, truly disruptive young companies that don’t have a splashy B2C concept and a great marketing gimmick. That’s ok. There is a place for more entertaining or corporate driven conferences with more flash, but for early startups, today there are much better options.

As the startup ecosystem in CEE gets more high-tech and less flashy and B2C, personal interaction is more important than ever.

At conferences like Wolves or Startup Fair Lithuania, speakers are unpaid volunteers, meaning only those with a strong urge to share their stories and a good reason to do so are speaking to smaller groups who are attracted by more than just a name or someone’s impressive resume.

That’s good news as far as I’m concerned, because it means that increasingly conference organizers and startups are understanding what is really key about these events: becoming a place where the relevant parties can make connections with each other. Today you see fewer startups sending their head of marketing or sales to conferences, and more likely you see the CEO and CTO there themselves. Even companies that are later stage seem to be doing this more.

Are Pitches Still Relevant?

Very much so. But not in the way they used to be. Not only conferences, but also accelerators and incubators have been recently questioning the pitch format for Demo Days as well. The key criticisms are exactly the same as for conferences, which is why at StartupYard we’ve continued to evolve the format to bring the greatest value to investors, community members, and startups.

We still strongly believe that preparing a killer pitch is a very important discipline for a young company and a first-time founder to master well. It forces founders out of their personal bubble, and defining the content of a pitch demands that startups make tough and necessary decisions, while striving to achieve things quickly that can become part of their story. All that is good and very much needed.

At the same though, much else has changed. For example, the stage portions of our Demo Days are now shorter than they were before. We’ve reduced keynotes significantly from the past (they used to take an hour or more), and we focus on holding the Demo Days in spaces where our startups can have meaningful contact with attendees after the pitch, and for much longer, up from maybe an hour in the past to multiple hours of 1 to 1 and group conversations. Demo Days are becoming more interactive as time goes on, and I see this happening in other accelerators as well.

We also introduced an official “Investor Week” a few years ago, and that has grown very popular. Investors who attend the Demo Day can now book a meeting with any of our startups in the following week, eliminating the fear that they won’t get in any facetime with the companies they want to meet.

Pitches are still relevant. But today’s connected world means that content is easy to share and to find. Personal contact, face to face, is more valuable as a result. By all means, work on your pitch, do your pitch, share your pitch, but don’t forget what a pitch should lead to: a real conversation.

How Smart Startups Keep Mentors Engaged

/in Life at an Accelerator, Marketing, Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYardA version of this post originally appeared on the StartupYard blog in January 2016. As a new group of Startups joins us in the next few weeks for StartupYard Batch 10, we thought we’d dive back into a very important topic for them: How do the smartest startups engage their mentors?

But first: why do some of even the most successful startup founders continue to seek mentorship?

Strong Mentors are Core to a Successful Startup

Mergim Cahani (right), CEO of Gjirafa, one of StartupYard’s most successful alumni, is an avid startup mentor himself.

Founders have to balance mentorship with the day-to-day responsibilities of their companies. But sometimes founders approach mentorship as a kind of “detour” from their normal operations- something they can get through before “getting back to work.”

This is the wrong approach. Having worked with scores of startups myself, as a mentor, investor, and at StartupYard, I can comfortably say that those who engage with mentors most, get the most productive work done. Those who engage least, are generally the most likely to waste precious time.

How can that be? Well, simply put, the first line of defense against the dumbest, most avoidable mistakes, are mentors who have made those mistakes themselves. I’ve seen this happen: a startup decides they’re going to try a certain thing, and it’s going to take X amount of work (often a lot of work). They mention it to a mentor, who forcefully advises that they not do it. The mentor tried it themselves, and failed.

Now this startup has 2 options: proceed knowing how and why the mentor failed, or change direction to avoid the same problems. Either way, an hour-long discussion with a mentor will probably have saved time and money, simply by raising awareness. I have seen 20 minute conversations with mentors save literally months of pain and struggle for startup founders.

Recently, one of our founders reached out to a handful of mentors for information on an investor who was very close to signing on as an Angel. The reaction was swift, and saved the founder from making a very serious mistake. The investor turned out to have a bad reputation, and was a huge risk. As a result, mentors scrambled to suggest alternatives and offer help securing the funds elsewhere. That is what engaged mentors can do for startups.

Engaged Mentors Defeat Wishful Thinking

There’s a tendency, particularly among startups that haven’t had enough challenging interactions with outsiders, to paper-over issues that the founders prefer not to think about. Often there “just isn’t enough data,” to prove or disprove the founders’ theories about the market.

Conveniently, “lack of data,” or “need for further study,” can serve as an excuse for not making decisions. That’s one of the main reasons startups fail – refusing to make a decision before it’s too late.

We like to focus on things we can control, and things we have a hard time working out appear to be outside of that sphere, so we are more likely to ignore them, or hand-wave their importance away.

Founders sometimes long to go back into “builder mode,” and focus solely on executing all the advice they’ve been given. And they do usually still have a lot of building to do. But one common mistake -something we see every single year- is that startups will treat mentors as the source of individual ideas or advice, but not as a wellspring of continuing support and continual challenges.

The truth is that a great mentor will continually put a brake on your worst habits as a company. They will be a steadfast advocate of a certain point of view- hopefully one that differs from your own, and makes you better at answering tough questions. But you have to bring them in.

Treat Your Mentors like Precious Resources

I can’t say how many times great mentors, who have had big impacts on the teams they have worked with, have come to me asking for updates about those teams. These mentors would probably be flattered to hear what an effect they’ve had on their favorite startups, but the startups often won’t tell them. And the mentors, not knowing whether they’ve been listened to, don’t press the issue either.

Mentors need care and feeding. They need love. Like in any relationship, this requires effort on both sides.

But time and again, mentors who are ready to offer support, further contacts, and more, are simply left with the impression that the startup isn’t doing anything, much less anything they recommended or hoped the startup would try.

Mentors who aren’t engaged with a startup’s activities won’t mention them to colleagues and friends. They won’t brag about progress they don’t know about, and they won’t think of the startup the next time they meet someone who would be an interesting contact for the founders.

This isn’t terribly complicated stuff. Many founders fear at first that “spamming” or “networking,” is the act of the desperate and the unloved. If their ideas are brilliant and their products genius, then surely success will simply find them. Or so the thinking goes.

Alas, that’s a powerful Silicon Valley myth. And believe me: it doesn’t apply to you. Engaging mentors is just like engaging customers: even if you’re Steve Jobs or Elon Musk, you still need to be challenged and questioned. You still need support.

As always, there are a few simple best practices to follow.

1. A Mentor Newsletter

Two of StartupYard’s best Alumni, Gjirafa and TeskaLabs, provide regular “Mentor Update” newsletters. These letters can follow a few different formats, but the important things are these: be consistent in format, and update regularly. Ales Teska, TeskaLab’s founder, sends a monthly update to all mentors and advisors.

In the email, he has 4 major sections. Here they are with explanations of the purpose of each:

Introduction

Here you give a personal account of how things are going. You can mention personal news, or news about the team, offices, team activities, and other minutiae. This is a good place to tell small stories that may be interesting to your mentors, and will help them to feel they know you better. Did a member of the team become a parent? Tell it here. Did you travel to Dubai on business? Give a quick account of the trip.

Ask

This is one section which I love about Ales’s emails. I always scroll down to the “ask” section, and read it right away. Here, Ales comes up with a new request for his mentors every single time. It can be something simple like: “we really need a good coffee provider for the office,” to something bigger, like “we are looking for an all-star security-focused salesman with 10 years experience.”

Whatever it is, he engages his mentors to answer the questions they know, by replying directly to the email. This way, he can gauge who is reading the emails, and he can very quickly get great answers to important questions or requests.

Audience engagement happens on many levels. Not everything engages every mentor all the time, and that’s important to keep in mind. A simple question can start an important conversation. You don’t know what a mentor has to offer you until you find the right way to ask for their help.

Wins

Here, Ales usually shares any good news he has about the company. This section is invaluable, because it reminds mentors that the company is moving forward, and making gains. A win can be anything positive. You can say that a win was hiring a great new developer, or finally getting the perfect offices. Or it can be an investment or a new client contact. These show mentors that you are working hard, and that you are making progress and experiencing some form of traction.

You’d be surprised how many mentors simply assume that a startup that isn’t talking about any successes, must have already failed. StartupLand in can be like Hollywood that way: if you haven’t seen someone’s name on the billboards lately, it means they’ve washed out.

The fact might be that you’re quietly doing great business, but see what happens when someone asks about you to a mentor who hasn’t heard anything in 6 months. “Those guys? I don’t know… I guess they aren’t doing much, I haven’t heard from them in a while.” There’s no good reason for that conversation to happen that way.

KPIs

Here Ales shares a consistent set of Key Performance Indicators. In his case, it is about the company’s sales pipeline, but for other companies, it might be slightly different items, such as “time on site,” or “number of daily logins,” or “mentions in media.” Whatever KPIs are most important to your growth as a company, these should be shared proactively with your mentors.

If the news isn’t positive, then explain why. You can also have a little fun with this, and include silly KPIs like: “pizza consumed,” or “bugs found.” This exercise shows mentors that you are moving forward, and gives them a reliable and repeatable overview of what you’re experiencing in any given week.

I heard one mentor complaining not long ago about these types of emails. “The KPIs don’t change that much, it’s always the same thing.” But he was thinking about the startup in question. The fact that the KPIs hadn’t changed might be a bad sign to the mentor, but probably the absence of any contact would be worse. At least in this case, the mentor might care enough to reach out and ask what’s going on.

2. Care and Watering

Mentors aren’t mushrooms. They don’t do well in the dark. Once you’ve identified your most engaged mentors, you need to put in as much effort in growing your relationship as you expect to get back from them.

How can you grow a relationship with a mentor? Start by identifying what the mentor wishes to accomplish in their career, in their life, or in their work with you. Do they want to move up the career path? Do they want to do something good for the human race? Do they just want to feel needed or important?

A person’s motivations for mentorship can work to your advantage. Try and help them achieve their goals, so that they can help you achieve yours.

Does a mentor want his or her boss’s job? Feed them information that will help them get ahead of colleagues and stand out. Mention them in your PR, or on your blog to enhance their visibility.

Does the mentor want to be a humanitarian? Show them the positive effects they’ve had by sending them a letter, or inviting them to a dinner.

Does the founder yearn to be needed? Include his/her name in your newsletter and highlight their importance to your startup. These things are all easy to do, and can be the difference between a mentor choosing to help you, and finding other things to do with their busy schedules.

Photo by

Photo by