Dealing with Mentor WhipLash

Startups in any mentorship-based accelerator program should, obviously, meet a lot of mentors, investors, and advisors over the course of the program. Even outside of an accelerator program, early-stage startups tend to seek a lot of advice, and should try to meet with and listen to a broad range of people with different opinions.

Hard Questions

Something that we notice happening with our startups toward the end of StartupYard’s “mentor month,” is that founders start to get a bit tired of meeting with new people. This is, overall, a good sign. Frustration with mentorship means that they are starting to notice a consistent theme in the feedback they are getting, and they are probably ready to start executing on the feedback they’ve received so far.

This is why we do virtually all of our mentoring in such a compressed period of time. And It is time consuming. Every startup we’ve accelerated has given us the same feedback: “this is really taking a lot of time and energy!” It does, but if it’s used effectively, it will be worth it.

Common objections to a startup’s idea, to its plans, to its approach and view of the market, tend to become quite obvious when a founder hears them many times in quick succession. A period of organized mentoring can allow a founder to develop strategies for answering the most common objections, and it can reveal objections to which their answers aren’t good enough yet.

If you aren’t tired of mentoring, you haven’t done it enough.

The best startup mentors are not necessarily those who just give startups clear instructions on what to do next. The best mentors ask the hardest questions. “How do you know that?” “What proof do you have for this assumption?” Good, searching questions can reveal to founders how weak the foundations of their thinking can at times be. When startup founders tend to rest their hopes on these assumptions, good mentors seek to poke holes in the theory of a startup, in order to make it stronger.

As mentoring goes on, there are fewer “ahah” moments for founders, and it becomes easier for them to answer tough questions that insightful mentors bring up. They start to be better at handling common objections, and identifying objections that do really demand more work on their part. They start, in short, to grow a pretty thick skin for new feedback, and they become less questioning of themselves, and more questioning of the mentors.

I can spot founders who have had good mentors by the way they deal with my questions: they’ve heard them all before, and they have answers that make sense, and that don’t ignore the question, or attempt to change the subject. They don’t dismiss the objections: they answer them convincingly and easily.

That growing confidence is double edged of course– too much mentoring can make founders immune to hearing new ideas over time– but just as importantly, it can make them more immune to what prominent VC Fred Wilson calls “mentor whiplash.”

Mentor Whiplash

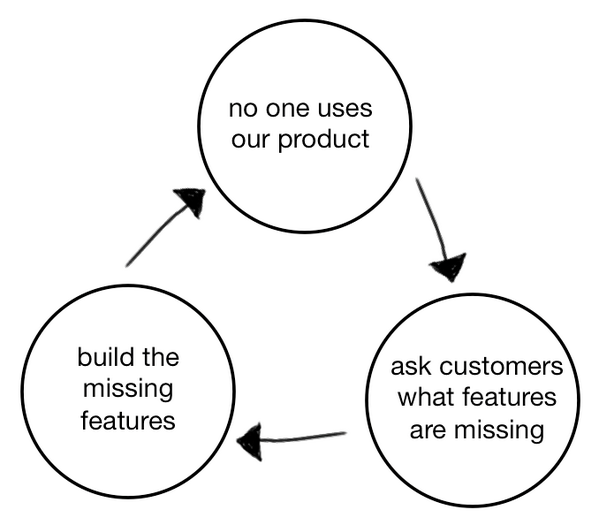

Every startup has at least a handful of these experiences in our program, and in every accelerator program in the world. Mentors often leap to radically different conclusions, and offer radically different advice to startups.

When one expert tells you that you absolutely have to do X, and another equally experienced mentor tells you that Y is absolutely, without a doubt, the way to go, and X and Y are mutually exclusive, what do you do? You may not know who to believe at this point.

The fault isn’t with the mentors. Mentoring can be difficult for both sides of the equation. I sometimes feel like my advice roles off startups like water off a duck’s back. It takes a long time, and a lot of effort, to make certain ideas stick. So I become quite forceful with my opinion. That’s a natural tendency for a mentor to have. Suggestions become commandments to be followed.

What startup founders learn over time, is that clearly two mentors with opposing views can’t both be right, but that both mentors may not necessarily be wrong. In the aggregate, over many sessions with many different people, a path will emerge. The founder’s job is to synthesize all that input into a plan that makes sense.

There will always be smart people who don’t buy your ideas, or who think you’re doing everything wrong. But if there were someone who knew exactly what you should do in all circumstances, then that person would surely be the richest person who ever lived.

Sounds Smart Vs. Is Smart

Really engaged mentors and advisors get to be fans of their chosen startups. We root for them, and we start thinking we know what’s best for them all the time.

Like being a fan of a sports team: it’s all the feeling of accomplishment, without having balls kicked at them at high speed.

It’s easy to spend 30 minutes with a startup, and give them the impression that you know your stuff. It’s much, much harder to do the work that startups do, which involves making something out of nothing. Mentors are domain experts, but not always startup founders themselves. They know their domains and they know their own jobs, but they won’t really appreciate the responsibilities of the person sitting across from them. How could they?

Sounding smart takes only experience. You can make an idea sound appealing if you know how to sell it. But being smart involves trial and error. An idea isn’t smart until it actually works, and this is largely in the execution, which can change over time. The work always ends up being worth more than the inspiration.

Keep Your Compass On You

We work hard to make sure our investor mentors aren’t seagulls (the kind who shit on an idea to make themselves feel more important, and then fly off). And we also work to make sure our mentors are focused on the needs of startups, rather than the needs of ego.

But one inherent danger, especially in a formalized mentorship setting, is that mentors never have the same motivations as startups. They can try to put themselves in the place of the founders, and sympathize with their experiences. The best mentors do this well, and continue to do it long after the first meeting.

However, mentors have things that they also believe in, and a way of seeing the world that they don’t necessarily share with a startup founder. Mentors can push a startup to think about things from their own perspective, which is fine, but they can also forget that their perspective is unique to them.

If a mentor is a VC, they may complain to a startup that they aren’t thinking big enough. If the mentor is a marketer, they may push the startup to think in terms of their own experiences.

This is all necessary input for startups, if they keep in mind that mentors speak for themselves, and about themselves, as much as they do about the startups they are counseling. A mentor has to dig into their own history, to offer startups the benefit of their experience. It is still the founder’s job to make sense of that experience for themselves.

A mentor’s experience and their opinion are separate things, which is important to remember. A mentor may have failed at what a founder is trying to do, or may have seen others fail. The founder can learn from that experience without heeding all the mentor’s advice; advice like: “don’t do it, it won’t work!”

Make A Mentorship Map

Effective mentors accelerate the growth of your ideas, but also, just as importantly, the growth of your personal network. They can give you contacts and directions to explore, and it becomes a complex undertaking to follow up on and use all the input and contacts you get.

One of the single biggest failings that early stage startups have, is that they don’t adequately follow up on the contacts offered to them by mentors. Every startup is guilty of that to a degree, which is unavoidable. Still, our most successful startups have been those who have pursued contacts relentlessly, both during and after our program.

Fred Wilson recommends that startups keep a feedback spreadsheet for input and contacts from mentors. That’s sound advice, and it’s something we require our startups to do. But I would also suggest a slightly more creative approach, that might work better for startups who are getting a lot of mentor whiplash: a mind map for feedback.

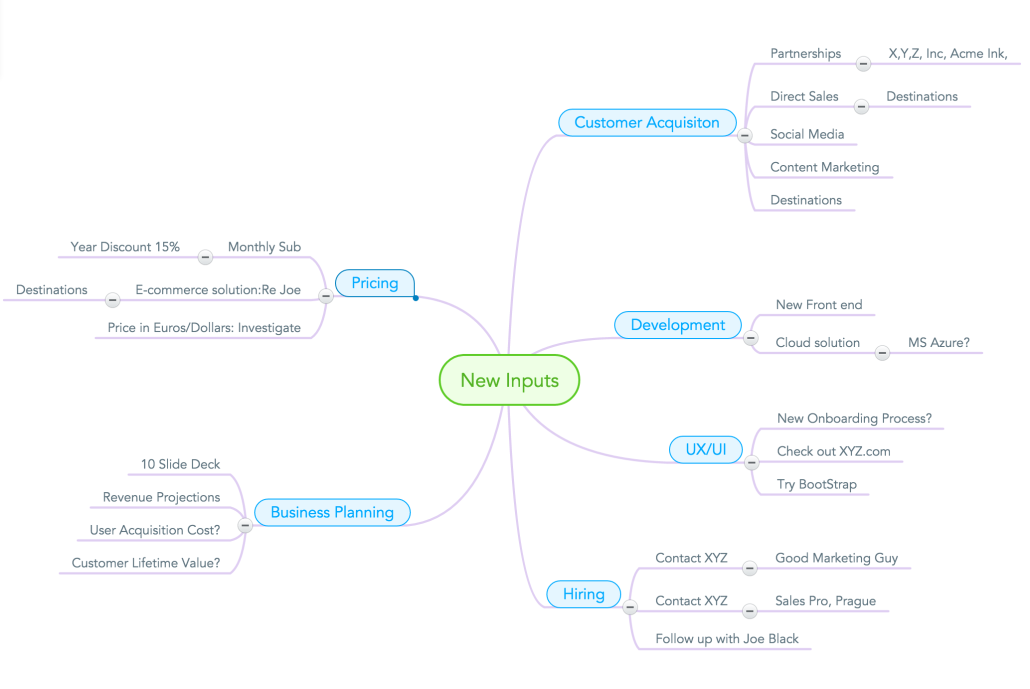

Your mindmap might look very different from this one, but here’s a possible example using MindMeister.com:

You could go into much more depth, and create a mindmap for each general category, employing each one for each different type of mentor, with a mindmap for Marketing, another for Investment, one for partnerships, etc. Or you could create a mindmap for each mentor individually.

It takes a bit of time to get used to mindmapping, but it’s a good skill to have when you need to have a reliable way of processing a lot of input from many different sources. Over time, you can customize your map to show your own priorities and the frequency of certain types of feedback as well.