Your Landing Page Sucks (Yes, Still)

/in Marketing, Startup Tools/by StartupYardThe Landing Page. Yes, in 2018, this is still an important part of your arsenal of marketing skills as a startup. That’s why at StartupYard, I still do a full-on workshop on just this topic, and why with every startup we accelerate, we drill these basic themes over and over again.

Why? Because the ability to write and execute an effective landing page depends on a very clear grasp of good marketing in general. A landing page is a “single serving communication,” or a piece of marketing that has to speak for itself, and be judged on its own. So it is also a great testbed for ideas, and seeing what works, or doesn’t work.

Since we face many of the same challenges with startups year after year, I thought it was high time to publish a post about the basic principles behind an effective landing page. These strategies can be used in many forms of communication (like email), because they focus on understanding the *why* of messaging decisions, rather than the *what* of any particular message.

What is a Landing Page?

For the purposes of this discussion, a landing page is a part of your website (or online product) where visitors “land” first. Depending on what kind of company you are, you might have only one landing page: your Homepage. Or you might have many. A blog post can serve as a landing page if it is meant to draw people in via search or social media.

Here are some examples of successful modern landing pages of different kinds. Take a moment and appreciate what about them is consistent and familiar.

In this discussion, we’re going to follow the KISS principle, and only talk about one kind of landing page, which is the single-purpose landing page, with one target audience, one message, and one call to action.

The Trust Pizza

Over the years, I’ve worked as a copywriter on uncountable landing pages, and other single-use marketing materials for scores of startups. I’ve devised a very simple formula for determining whether I am being effective with a particular page.

Content is King, as we say. A great message is most important. But an effective message follows from the right approach. Having a formal structure that is designed to be foolproof is important in helping you shape a message.

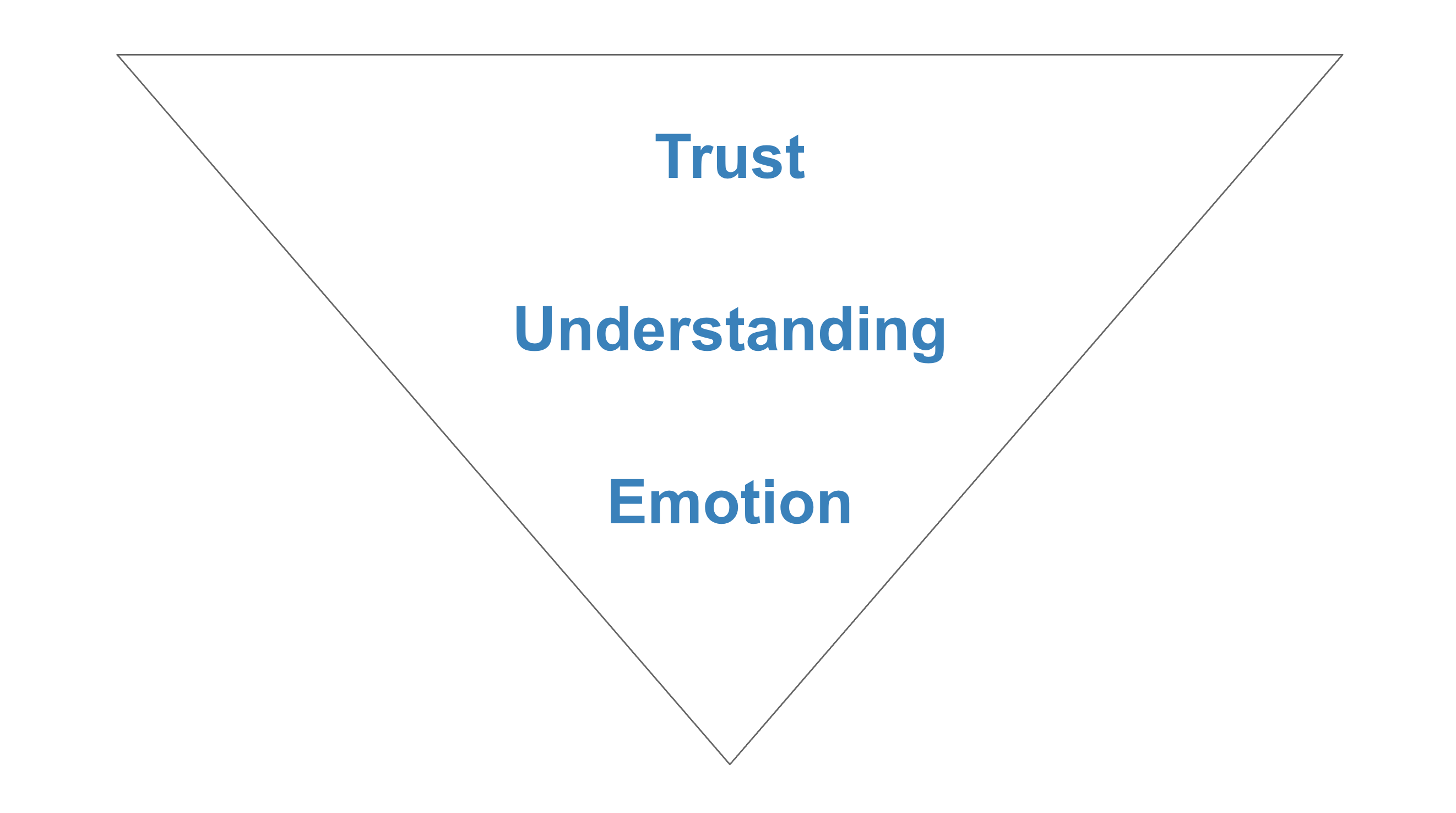

My formal approach is simple. I call it the “trust pizza.” Here’s what it looks like:

What is important about the Trust Pizza is its shape and the order of ingredients. Follow this simple strategy, and you’re much more able to judge whether your landing page is likely to work or not.

-

Trust = Crust

The most boring but essential element of the pizza is the crust. Not only do we grab a pizza by the crust, we also use the crust to judge the pizza overall.

Just think about evaluating a pizza. If the crust is burnt, what does that tell you about the overall quality of the thing? On the other hand, if the crust is soft and inviting, then you know the pizza will probably be good. Looking at the middle of the pizza tells us very little about it: it might be good, but we can’t know.

The “outer layer” of a landing page is just like that. Trust is composed of every background element of your page. Do you have a header and footer? Do you have appropriate links and contact details? Is the font, color and any background image on-brand?

You should spend as much time on these details as you do on the central message of a landing page. These things tell us whether you can be trusted at all, much less believed in this particular case. Get them wrong, and forget about anyone taking a “bite” out of your landing page.

The trust crust also reminds us not to get too clever. At the end of the day, no matter how revolutionary the idea, a pizza still looks like a pizza. So it is with a landing page. The content should be interesting, but not *less interesting* than the format.

Not only confusing, but actually disgusting.

If you want to give the impression that you’re incredibly hip and modern, do so with the understanding that this may be the only message that gets across. I may admire a pizza shaped like the Eiffel tower, but I don’t want to eat it.

2. Understanding = Toppings

The “understanding” aspect of your landing page is the heart of the message. It is the information you want to convey. It’s often a number or a date. It’s a key point. If a visitor remembers anything about you, it should be this.

Of course when you order a pizza, the toppings are the focus. They differentiate your pizza from all other pizzas. Cheese and pepperoni is totally different from a cream sauce with BBQ chicken.

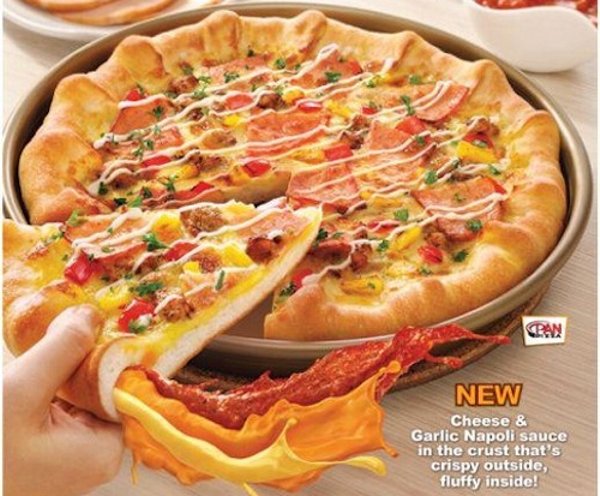

But remember: an effective pizza has only the right combination of toppings. Go too crazy, and you turn something good into something truly nasty. Burgers are good. Fries are good. Nuggets are good. But all 3 on a pizza are not good, they’re gross.

Adhere to the KISS principle (Keep it Simple Stupid), when choosing your toppings. If you aren’t sure how to blend two ideas together, then don’t try. Choose the most important one, and go with that.

Better a few good toppings than a mess of bad ones, right?

All of these things individually are amazing. All of them together are horrifying.

3. Emotion = The First Bite

Finally the good stuff. The pointy edge of your landing page pizza is the spot at which a customer will “bite.” So you need to give them a good reason to do so. You’ve presented an appealing crust, a nice set of toppings, and now you want a nice, crisp wedge shape to finish the job.

This is the Call to Action. The button, or other cue which should prompt a person to do something (take a bite of the pizza), and be led somewhere else on your website, or in your customer funnel.

The call to action is the simplest but often most important part of a page. It prompts the user with their next move, and at the same time must show them exactly what happens when they click the button, follow the link, or enter their information. The “ first bite” has to be rewarding enough: it has to be mouth watering.

The Pizza Shaped Landing Page

The above is a tool for planning and assembling the elements of your marketing message for a landing page. But remember that just as you must form a pizza from raw ingredients into a certain shape, so must you shape a landing page to be enticing and “edible.”

One of the keys here is “visual momentum,” or what I call the pinball effect. That is, the attention and visual interest of the page should eventually lead down to the place where you want eyeballs to be. It can’t *start* there, but it shouldn’t end somewhere else. No big exciting things to see off to the side. No distractions: just one bigger message leader to a smaller one, leading to a simple action.

In principle, you should try to keep the three key sections of your landing page organized in order of interest:

- The Headline

- The Body (or Subhead)

- The Call to Action

The Headline

The headline, while simple, should grab the most interest from the beginning. It is something bold and maybe unexpected. It is not, I repeat, *NOT* a list of buzzy words like: “Analyze. Evaluate. Innovate.”

That’s just lame folks. Your headline needs to be a statement about why you’re different. It should be something ripped straight from the “unlike” section of your positioning statement. It can even be negative: “Don’t Be Lame,” or “Had Enough BS for One Day?”

That’s an eye-catching statement. Something weak and defensive is not eye-catching. “We Care about You,” is not compelling. “Our Customers Come First,” is an eye-roll at best. Say something definitive about what makes you different, and more importantly, why your customer should even care.

Remember: the Headline is about letting the visitor know what they’re in for. It’s a signal of what’s to come. So it needs to be a strong one.

The Body (Or SubHead)

Here you have the most freedom. It’s toppings time! You should include numbers, or statistics, or outcomes that your product or service will provide. What’s the difference between a pizza you love and one you hate on sight? The toppings.

“Trusted by 3 of 4 Startups,” for example, or “Proven to lower your costs by 30%.” These are informative, direct statements about what the product is promising to do for the customer. They’re beautiful sausage and pepperoni, or olives if that’s your thing.

If the landing page is for an event or a sale, then it might be time to include the date or time.

Remember the It’s Not About You principle. This is not the time to explain that you are a bio-organic-cruelty-free-lactose-intolerant team of albino hemophiliacs who identify as lawn ornaments. The customer wants to hear what’s in it for them. You’re trying to tell them you’re using artisanal cheeses made by blind pagan craftsmen in the alps, but they want to know if the pizza is vegetarian or meat-lovers. They want the facts, not the fluff.

Now is also *not* the time to sell or urge action. Don’t jump the gun here. You’re being informative. You’re showing the meat of the offer, not closing the sale.

The Call to Action (Take a Bite)

Now you’re closing. The call to action is simple but very tricky. You want to accomplish a bunch of objectives at once, to some degree or another. You want the visitor to know a number of things:

- What am I supposed to do

- When am I supposed to do it

- What will happen

- When will it happen

And remember, this is a call to action that may be as long as two or three words. It has to accomplish a lot in that space of time. It needs to rely on context and build upon the preceding elements to do that.

But always consider the call to action in this context: Is it clear to the reader exactly what will happen when they press that button? And is what they think is going to happen the same as what will actually happen? As a landing page is meant to create a relationship, you need to start it off by delivering on what you’ve promised.

Don’t offer something in your call to action that you can’t deliver. Don’t lie. Don’t even get close to maybe being a little bit dishonest. Just don’t do it.

Here are some common “Call to Action Lies” to avoid, along with the reasons they suck:

- It’s Free! [But give us your credit card lol it’s not free]

- Start Your Trial [Actually give us your contact so we can sell you]

- Get it Now [But you have to wait a while]

- Get the Beta [When it’s ready if ever]

- Learn More [Just kidding lol buy now]

Instead, a call to action should do exactly what the user expects. If you want their email, say: “Enter Your Email,” if you want them to buy, say: “Buy Now, Save X.” If you want them to demo the product, then make the demo accessible when you say it will be.

Remember: If you’re thinking it’s a cheat, then your visitor is too. Don’t treat your customers as dumber than you are. Assume they’re smarter.

Stick to the Trust Pizza

Remember, whatever decisions you make about *what* to communicate, never forget the importance of *how* you communicate it. In my experience, more than half of the message is not the words you use, but rather their format.

Does it look right? Does it make visual sense? Is it weird or somehow off? These details make or break a landing page much more easily than a less than perfect turn of phrase. Stick to the pizza. Don’t reinvent it.

The StartupYard Big Book of Marketing

/in Marketing, Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYardThe StartupYard Big Book of Pitching

/in Marketing, Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYardHow Smart Startups Keep Mentors Engaged

/in Life at an Accelerator, Marketing, Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYardA version of this post originally appeared on the StartupYard blog in January 2016. As a new group of Startups joins us in the next few weeks for StartupYard Batch 10, we thought we’d dive back into a very important topic for them: How do the smartest startups engage their mentors?

But first: why do some of even the most successful startup founders continue to seek mentorship?

Strong Mentors are Core to a Successful Startup

Mergim Cahani (right), CEO of Gjirafa, one of StartupYard’s most successful alumni, is an avid startup mentor himself.

Founders have to balance mentorship with the day-to-day responsibilities of their companies. But sometimes founders approach mentorship as a kind of “detour” from their normal operations- something they can get through before “getting back to work.”

This is the wrong approach. Having worked with scores of startups myself, as a mentor, investor, and at StartupYard, I can comfortably say that those who engage with mentors most, get the most productive work done. Those who engage least, are generally the most likely to waste precious time.

How can that be? Well, simply put, the first line of defense against the dumbest, most avoidable mistakes, are mentors who have made those mistakes themselves. I’ve seen this happen: a startup decides they’re going to try a certain thing, and it’s going to take X amount of work (often a lot of work). They mention it to a mentor, who forcefully advises that they not do it. The mentor tried it themselves, and failed.

Now this startup has 2 options: proceed knowing how and why the mentor failed, or change direction to avoid the same problems. Either way, an hour-long discussion with a mentor will probably have saved time and money, simply by raising awareness. I have seen 20 minute conversations with mentors save literally months of pain and struggle for startup founders.

Recently, one of our founders reached out to a handful of mentors for information on an investor who was very close to signing on as an Angel. The reaction was swift, and saved the founder from making a very serious mistake. The investor turned out to have a bad reputation, and was a huge risk. As a result, mentors scrambled to suggest alternatives and offer help securing the funds elsewhere. That is what engaged mentors can do for startups.

Engaged Mentors Defeat Wishful Thinking

There’s a tendency, particularly among startups that haven’t had enough challenging interactions with outsiders, to paper-over issues that the founders prefer not to think about. Often there “just isn’t enough data,” to prove or disprove the founders’ theories about the market.

Conveniently, “lack of data,” or “need for further study,” can serve as an excuse for not making decisions. That’s one of the main reasons startups fail – refusing to make a decision before it’s too late.

We like to focus on things we can control, and things we have a hard time working out appear to be outside of that sphere, so we are more likely to ignore them, or hand-wave their importance away.

Founders sometimes long to go back into “builder mode,” and focus solely on executing all the advice they’ve been given. And they do usually still have a lot of building to do. But one common mistake -something we see every single year- is that startups will treat mentors as the source of individual ideas or advice, but not as a wellspring of continuing support and continual challenges.

The truth is that a great mentor will continually put a brake on your worst habits as a company. They will be a steadfast advocate of a certain point of view- hopefully one that differs from your own, and makes you better at answering tough questions. But you have to bring them in.

Treat Your Mentors like Precious Resources

I can’t say how many times great mentors, who have had big impacts on the teams they have worked with, have come to me asking for updates about those teams. These mentors would probably be flattered to hear what an effect they’ve had on their favorite startups, but the startups often won’t tell them. And the mentors, not knowing whether they’ve been listened to, don’t press the issue either.

Mentors need care and feeding. They need love. Like in any relationship, this requires effort on both sides.

But time and again, mentors who are ready to offer support, further contacts, and more, are simply left with the impression that the startup isn’t doing anything, much less anything they recommended or hoped the startup would try.

Mentors who aren’t engaged with a startup’s activities won’t mention them to colleagues and friends. They won’t brag about progress they don’t know about, and they won’t think of the startup the next time they meet someone who would be an interesting contact for the founders.

This isn’t terribly complicated stuff. Many founders fear at first that “spamming” or “networking,” is the act of the desperate and the unloved. If their ideas are brilliant and their products genius, then surely success will simply find them. Or so the thinking goes.

Alas, that’s a powerful Silicon Valley myth. And believe me: it doesn’t apply to you. Engaging mentors is just like engaging customers: even if you’re Steve Jobs or Elon Musk, you still need to be challenged and questioned. You still need support.

As always, there are a few simple best practices to follow.

1. A Mentor Newsletter

Two of StartupYard’s best Alumni, Gjirafa and TeskaLabs, provide regular “Mentor Update” newsletters. These letters can follow a few different formats, but the important things are these: be consistent in format, and update regularly. Ales Teska, TeskaLab’s founder, sends a monthly update to all mentors and advisors.

In the email, he has 4 major sections. Here they are with explanations of the purpose of each:

Introduction

Here you give a personal account of how things are going. You can mention personal news, or news about the team, offices, team activities, and other minutiae. This is a good place to tell small stories that may be interesting to your mentors, and will help them to feel they know you better. Did a member of the team become a parent? Tell it here. Did you travel to Dubai on business? Give a quick account of the trip.

Ask

This is one section which I love about Ales’s emails. I always scroll down to the “ask” section, and read it right away. Here, Ales comes up with a new request for his mentors every single time. It can be something simple like: “we really need a good coffee provider for the office,” to something bigger, like “we are looking for an all-star security-focused salesman with 10 years experience.”

Whatever it is, he engages his mentors to answer the questions they know, by replying directly to the email. This way, he can gauge who is reading the emails, and he can very quickly get great answers to important questions or requests.

Audience engagement happens on many levels. Not everything engages every mentor all the time, and that’s important to keep in mind. A simple question can start an important conversation. You don’t know what a mentor has to offer you until you find the right way to ask for their help.

Wins

Here, Ales usually shares any good news he has about the company. This section is invaluable, because it reminds mentors that the company is moving forward, and making gains. A win can be anything positive. You can say that a win was hiring a great new developer, or finally getting the perfect offices. Or it can be an investment or a new client contact. These show mentors that you are working hard, and that you are making progress and experiencing some form of traction.

You’d be surprised how many mentors simply assume that a startup that isn’t talking about any successes, must have already failed. StartupLand in can be like Hollywood that way: if you haven’t seen someone’s name on the billboards lately, it means they’ve washed out.

The fact might be that you’re quietly doing great business, but see what happens when someone asks about you to a mentor who hasn’t heard anything in 6 months. “Those guys? I don’t know… I guess they aren’t doing much, I haven’t heard from them in a while.” There’s no good reason for that conversation to happen that way.

KPIs

Here Ales shares a consistent set of Key Performance Indicators. In his case, it is about the company’s sales pipeline, but for other companies, it might be slightly different items, such as “time on site,” or “number of daily logins,” or “mentions in media.” Whatever KPIs are most important to your growth as a company, these should be shared proactively with your mentors.

If the news isn’t positive, then explain why. You can also have a little fun with this, and include silly KPIs like: “pizza consumed,” or “bugs found.” This exercise shows mentors that you are moving forward, and gives them a reliable and repeatable overview of what you’re experiencing in any given week.

I heard one mentor complaining not long ago about these types of emails. “The KPIs don’t change that much, it’s always the same thing.” But he was thinking about the startup in question. The fact that the KPIs hadn’t changed might be a bad sign to the mentor, but probably the absence of any contact would be worse. At least in this case, the mentor might care enough to reach out and ask what’s going on.

2. Care and Watering

Mentors aren’t mushrooms. They don’t do well in the dark. Once you’ve identified your most engaged mentors, you need to put in as much effort in growing your relationship as you expect to get back from them.

How can you grow a relationship with a mentor? Start by identifying what the mentor wishes to accomplish in their career, in their life, or in their work with you. Do they want to move up the career path? Do they want to do something good for the human race? Do they just want to feel needed or important?

A person’s motivations for mentorship can work to your advantage. Try and help them achieve their goals, so that they can help you achieve yours.

Does a mentor want his or her boss’s job? Feed them information that will help them get ahead of colleagues and stand out. Mention them in your PR, or on your blog to enhance their visibility.

Does the mentor want to be a humanitarian? Show them the positive effects they’ve had by sending them a letter, or inviting them to a dinner.

Does the founder yearn to be needed? Include his/her name in your newsletter and highlight their importance to your startup. These things are all easy to do, and can be the difference between a mentor choosing to help you, and finding other things to do with their busy schedules.

Startup Skills: How to Create a Killer Talk

/in Marketing, Startup Tools, StartupYard News/by StartupYard5 Surprising B2C Growth Strategies Founders Rarely Try

/in Life at an Accelerator, Marketing, Startup Tools/by StartupYardI’m not a fan of so-called “growth guruism,” or a believer that so called “Growth Hacking,” is what separates successful startups from failures. Solving problems that matter, taking pains to understand your customers and your market deeply, and doing truly unique and challenging things set the best tech startups apart- not the tricks they use, but how they use them.

Still, a growth strategy doesn’t hurt. Netflix wouldn’t be Netflix if it didn’t have clever marketing back when it launched. But it might not be Netflix the global dominant SVOD platform if it hadn’t sent its early-days DVDs to customers by mail in bright, flashy red envelopes, making customers proud to evangelize a sexy new product.

Even absent a full-blown growth strategy, it often surprises me that more founders don’t do relatively simple things that can help them grow much faster, and fine tune their marketing and sales efforts much more quickly.

So that’s what this is, a list of simple growth ideas that most people don’t bother to try, but which may just work for you. As a bonus, I’ll be adding real world examples that you can study on your own more closely.

1. Tame Your Mavens

There are lots of ways to launch a B2C online product. There is no right way, but there are plenty of wrong ways.

Something pretty much every B2C company I’ve worked with has struggled at some point to gain traction for the launch of a new product. It gets a lot easier once you have a following and a track record with loyal customers, but your first product is like your first date. If it starts off badly, things usually don’t get very far.

Bad Version: The “I Hope This Works” Strategy

To ensure your launch will get the traction they need, many startups will “soft-launch” – an intermediate step between a beta version and a market-ready product. A soft-launch may be just a stealth launch with no marketing attached to it. That relies on friends and your personal networks to begin creating buzz about the launch.

It might work, but then it might not. No way to know.

Better Version: The “Connoisseur” Strategy

You can and should think about putting a bit more punch into a soft-launch pitch. Instead of just meekly offering your product, and seeing what happens, identify and close a group of customers who will be ready to use it from Day 1.

Use your customer personas (I hope you’ve done them), to identify a group of people who are in your key demographic, and are influencers in your market, and among your customers. What does an influencer look like? Somebody with a strong social media presence, plenty of mentions in news articles, or a following for a product of their own.

This group is what marketers call the “Mavens.” They are the ones whose social capital is invested in spotting new trends and talking about them. They’re the self appointed taste-makers, and you need them to like you.

Once you have a list, do whatever you can to get these mavens onboard with your launch. Give them free stuff, promise them visibility, praise their god-like skills of discernment. Whatever you have to do to be their best friends, do that.

Ever wonder how those startups with cool ideas end up in the gadget section of the New York Times, or the front page of Wired? That’s a process that starts long before the launch. In fact the launch depends on that process succeeding. Startups with a great PR strategy pre-launch will time their launch around the PR, not the other way around.

Real World Examples:

Netflix targeted avid film buffs on early-internet chatrooms and indy film reviewers in the 1990s before launching their DVD delivery service.

IndieGogo and other crowdfunding platforms turned this strategy into their core businesses: getting product enthusiasts to pledge purchases and hype products in exchange for special access and perks.

2. Be Controversial, Asshole

![]()

Startup founders can spend a lot of time (maybe too much time) studying the every move of a Steve Jobs or an Elon Musk. We all learn that you need to act successful in order to be successful.

That’s fine and good, but don’t be fooled: you are not successful yet. Why do we talk about these people now? Because of how diplomatic and strategically minded they are? I think not. The things those entrepreneurs had to do to grow their reputations and businesses would look much different to us if they did and said the same things now.

I’m not telling you to be an asshole. There are plenty of very successful entrepreneurs who aren’t. But I am saying to speak your mind when you can, because later, you won’t get that chance. Consider Mark Zuckerberg ranting in the Harvard Crimson that he was smarter than the entire IT department of the university in 2003. Consider Steve Jobs frankly insulting his future boss John Scully by calling him a sugar-water salesman.

Or just consider any successful entrepreneur who made people question what they really believed about how things should work. Feelings get hurt in that process, and a small company looking for an edge can’t afford to worry too much about hurting people’s feelings, particularly people a lot more powerful than they are.

Real World Examples:

Bitcoin was launched by the anonymous “Satoshi Nakamoto” in 2009 via a controversial white-paper. Regarded by some as revolutionary and prescient, and seen by others as problematic in its economic theories, the paper continues to enforce the Nakamoto brand even years after its author receded into silence.

Google began its campaign to expand beyond its beginnings as a search engine and launch Gmail. The company adopted the motto “Don’t Be Evil,” which at the time was interpreted as a hard swipe at competitors (like Microsoft and Yahoo) that Google was positioning itself against as a new Big Tech player.

3. Have a Gimmick

There are a few kinds of gimmicks. There are physical gimmicks, like a piece of swag or a clever trinket related to the product, and there are software gimmicks, which are a kind of game or a tool your target customers will like. Let’s take this premise in 2 parts.

- The Physical Gimmick

A physical gimmick isn’t going to work for every company, because not everything lends itself to a physical hardware product. Then again, a lot of things really do.

Physical products, even very simple or decorative ones, offer an opportunity for your brand to reach customers in a new way. We are much more likely, as social creatures, to demonstrate new products we’ve brought to our friends and family if it has a physical component. This type of thing is sometimes referred to as “swag,” but a proper gimmick rises above the level of swag to become a part of the product experience.

Consider Google Cardboard – it’s a gimmick that advertises Google’s VR technology. Instead of a t-shirt or a coffee mug, customers get something that is contextual to the product itself. Because the product is also probably rare or unknown, it appeals to the human need for discovery and for “being first.”

How do you turn your product into a physical gimmick? There’s no one answer, but think about the ways in which your product is going to be used. What kind of physical tasks are involved? In what context will it be used? In the office? At home? On the toilet? In the car?

Not long ago one of our startups Beeem, the physical web company that helps retailers or venues broadcast webapps to nearby mobile devices, sent us a gift. They were standard sized “Business Cards,” enabled with Beeem’s beacon technology, that would broadcast a website where our LinkedIn profiles and emails would be accessible.

This is not really the business Beeem is in, but it’s a very clever growth idea. Now, whenever I talk about Beeem at a conference, I can whip out my business card and tell everyone how to get to my special, on-the-spot website from their mobile phones. It makes me seem geeky but cool, and it gets lots of people to try the service at once. Win, Win.

Real World Examples:

Revolut, the recently launched “post-banking” fintech company that offers virtual bank accounts and ultrafast and cheap currency conversion, used a very similar technique to the one I described above. They created blank credit cards, which they then distributed at events for free. Users could “claim” their card by opening an account on Revolut and putting some money on them. Which many, many people promptly did.

Amazon, when launching the Amazon Dash service (which allows customers to order specific items with one click), distributed small “Dash Buttons” to consumers to place in areas of their homes where certain products are used, such as laundry soap or food. Today Amazon has hundreds of these devices available to buy.

- The Software Gimmick

The other avenue for gimmicks is in software, either in a browser or via an app. A great example of a classic gimmick is The Calculator. Such as this Mortgage Calculator from NYT.

A software gimmick is something related to your product in some way, but appeals to your customers on its own, helping you to instill your brand in their minds. There are a number of classic gimmicks:

The Calculator: a tool to help your customers solve a specific problem related to the product (like the price of insurance, or the cost of owning something versus renting it).

The Map: A way for your customer to explore content or learn something with a geographical context. Examples: Airbnb, Kiwi.com

The Puzzle: A game to get your customer thinking about the problems that your product solves for them. Also a way to spread the world about the product. Example: Google Doodles

The Quiz: A questionnaire that gives the customer a feeling of accomplishment (and works well to qualify a customer for follow-up). Examples: commonly used on Facebook

The Secret: This is in the form of an easter-egg or a “lifehack,” that helps your customer accomplish something few other people know about. Examples: In&Out Burger, famous in the US for their “secret menu,” which contains a large list of items that are only available upon request. Google has famously introduced hundreds of easter egg functionalities, which fans share and explore regularly. By the way, if you haven’t already: Do a Barrel Roll.

4. Make it Rain – (Money, That Is)

The quickest route between two points is a straight line. This is as true in finding customers as in anything else.

One of the straightest lines to a customer is the offer of something for nothing. Pay your customers to be your customers.

While it doesn’t work for every startup, it has been proven over and over to work for a great many of them. In a B2C company, even a SaaS company, the classic marketing strategies still work fine. There are a lot of ways of getting people in the door to have a look around.

If you’re old enough, you might remember some of the classic tactics. Sending a potential customer a discount coupon with a specific cash value (only to be used for a purchase with the retailer). Promising every customer a cash rebate for signing up.

The classic rebate deal was essentially a way of giving a customer something for free, while also getting them to commit cash to the endeavor. That’s a classic foot-in-the-door tactic. Many younger entrepreneurs today are less familiar with these old-school techniques because they went out of fashion with the age of online ads. However, they are making a comeback today.

For example, the phenomenon of “pre-purchases,” particularly of products that are not actually constrained by distribution logistics. Yet companies like Apple and Amazon have brought back the practice in a big way, tapping into the same emotional experience that send-away catalogues relied on for a century before they were abolished in favor of websites and apps.

Even supposedly “crowdfunded” products are increasingly really just products in pre-sale. The shift toward a primarily marketing role among leading crowdfunding platforms has been noted for years. With good reason: the tantalizing appeal of something one cannot have is harder and harder to find in today’s online consumer world. Waiting can be a joyful experience, and it can make the product feel special and noteworthy.

Real Life Examples:

Damejidlo, our 2012 alum and now the dominant food delivery platform in Czechia, bought users by offering every new customer about €10 worth of free food. You could get more credits by bringing friends to the platform as well.

Uber and many other ride-hailing apps have also famously paid for customers, offering a free ride to newly registered users. Airbnb has offered similar deals to new customers, as well as hosts.

5. Become a Public Personality

Easier said than done, but it’s still worth a try. Becoming a known public face for your industry, or for the greater problem your company is solving, can open up an ocean of free publicity for what you make.

At StartupYard, for example, we operate on a loose rule that we don’t attend tech conferences unless we are allowed to speak at the event, such as on a panel, or a workshop or keynote. Once at the event, we apply our experience as presenters and coaches to try and be the most memorable and interesting speaker there.

By being controversial, being informative, and being most importantly fresh with our perspective, Cedric Maloux and I are both often identified as standout presenters. People frequently talk to us after speeches, and more importantly, they tell their friends about us. Being out there in public isn’t for everybody, but if you’re doing something that takes advocacy and education for people to understand and value, then you need to be a leader, and speak out.

Here are some things that can really help you transform yourself into a public personality:

Join Reddit channels in your industry, and follow topics on Quora. Take the time to build your reputation as an expert in the field you engage with. This takes time, but it also keeps you informed about what interests people, what’s being talked about, and what most people are missing in the conversation.

Join Competitions (with a goal). Pitching competitions, speaking competitions, even pub quizzes are going to help you build your confidence and assert yourself in front of strangers. Make yourself a goal of first attending a minimum number of competitions every month. When you get better at pitching or speaking, aim to win all the competitions you enter. Approach them as a game, not an opportunity, and try to win. If you win, opportunities will come to you.

Get speaking gigs. This means volunteer yourself to talk in front of groups of people. Be it technical, or business focused, government, corporate, or open source, get yourself on the list of speakers at relevant events and go out and talk about things you know matter. Be controversial. Be informative. And say something people haven’t heard before.

Get a speaking agent: If you’re highly skilled in your area of expertise, it’s quite possible there are people looking for speakers just like you, and even better, are willing to pay you to advertise yourself.

Our next post: How to Create a Killer Talk

StartupYard is currently accepting applications for Batch 9.

We’re looking for startup founders in Crypto, AI, IoT, and AR/VR!

Get started applying to StartupYard Batch 9. Applications close January 31st, 2018.

Friday Funnies: Thought Leaders

/in Life at an Accelerator, Marketing, Startup Tools/by StartupYard

Our Thoughts

Thoughts are very important. Leadership is very important. Thought leadership may be the most important development in thinking, or leadership, since before thought leadership.

In all seriousness, this video is a valuable teaching tool for StartupYard, and we use it to show startup founders that the elements of a convincing presentation are from a separate skill-set than a deep knowledge of what you’re actually doing.

Knowledge is never enough, but nailing the format is also never enough. Always, founders must compromise between what they know, and the things they need to do to gain the trust of others. We call it “being clear,” rather than “being accurate.”

You can now apply for StartupYard Batch #8.

- Robots

- Artificial Intelligence

- VR/AR

- IoT

- Cryptography

- Blockchain

Startups: It’s Time to Think Pricing. Here’s How.

/in Life at an Accelerator, Marketing, Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYardOut of 7 startups that joined us just a few weeks ago for StartupYard Batch 7, only 2 are currently selling a product to real customers. Those 2 have just a handful of customers each. Most of our startups are very early stage; you have to have something to sell, before you can sell. But it surprises many of them how early it pays to think pricing.

While we expend days and weeks and months of effort discussing features and USP, design and everything else, it’s surprising to me how difficult it really can be to talk to startups about pricing. Talking about pricing is kind of hard. People don’t want to think about it. They panic at the thought of raising prices, and they cower in fear of having prices too low. It can be a rollercoaster.

Of course, pricing is a sensitive subject. As Tom Whitwell writes in his insightful medium piece on pricing psychology, “Prices are a shortcut to our most sensitive emotional responses.” Pricing is a deeply primal part of consumer psychology, and as Whitwell shows, leaves consumers surprisingly, sometimes shockingly, susceptible to manipulation or suggestion.

I suggest you go and read that piece: The First Rule of Pricing, to find out why. I’ll wait.

…

Hello! Now that you’re back, this piece is going to build on Whitwall’s, to talk about what all that means for early stage startups, and how they should actually approach pricing their products for the first time, or through the first few iterations.

Your Customers Don’t Know What They Want (Or How Much They Would Pay)

As Malcolm Gladwell explored in his best-seller Blink, and associated Ted Talk “On Spaghetti Sauce,” it has been known in retail since the early 1980s that optimum sales results could not be achieved by finding the ideal single product and price point. For decades, product companies had been simplifying their offerings in the hopes of reducing costs while optimizing their sales around best-selling lines of products.

The logic was simple. The attractiveness of products could be graded on a bell curve. An ideal point was where most customers would be willing to buy, whether or not any of them were completely satisfied. Simple product lines also made advertising easier, reducing the need to target advertising to specific audiences, because increasingly, products were targeted at the vast middle of the market.

As he explains, beginning in the early 80s, big food companies, and later other product companies, discovered that this tendency to optimize around single products was hurting their profitability. Instead of selling one popular product that was a mix of the qualities most customers wanted, producers began to develop products that catered to “clusters” of customers who had distinct preferences.

Importantly, research showed that customers were not well equipped to predict what they would enjoy or what they would buy. As Gladwell notes, “For years and years, the standard practice when you wanted to find out what customers would want to buy… was to ask them.”

But customers routinely used experience as a reference point for future behavior. People are bad at imagining a future that isn’t similar to the present. Likewise, they are not good at predicting their future behaviors, because they assume their behaviors will remain consistent.

Experimental field research discovered that “hidden preferences” in consumer behavior were powerful, and almost completely unknown. By testing products with “value added” features, researchers found that price tolerance was much more flexible than previously believed.

For example, about ⅓ of US consumers enjoyed “Extra Chunky” spaghetti sauce. And yet no major brand offered such a product. Customers failed to state, when asked, that they wanted “chunky spaghetti sauce,” but experiments showed that when given the choice, they readily bought it and paid more for it.

Think Pricing

The post 80s flourishing of product segmentation was slow to be adopted for the digital economy. Driven by the technical difficulty of offering and maintaining more diverse product offerings at different pricing points, and the difficulty of marketing each individually in the online space, software and online companies often adopted the old model.

But today, tiered pricing has seen a major comeback. Customers are again comfortable with the concept applied to digital products. Thus instead of we have “9.99 for Standard, 14.99 for HD,” or the “Good, Better, Best” pricing model, in which features and functionalities are limited or exclusive to different products.

So what does this mean for your own pricing? First, there is no optimum pricing strategy- at least not in the sense that most startups tend to think. There is no perfect price, but rather a continuum of price and feature combinations, into which most customers fall somewhere. The work of a product company is to identify where pricing and feature expectations align for different categories of customers– what Gladwell calls “clustering.”

If you aren’t consistently testing the limits of your pricing and the feature expectations of your customers, then you will likely leave money on the table. Whitwell uses the example of The Times of London. Beginning in 2014, The Times began asking customers whether they would pay X amount for different combinations of features. They produced a range of prices and feature sets, to test different “flavors,” of plan to sell to their customers.

What they found shocked them. Although a minority of their customers would choose to pay more for certain features, the actual revenue to be gained from offering those features at a different price point far outweighed the lower number of paying users. They found that customers would gladly pay up to 3 times more than they currently did to retain only a portion of the same features they enjoyed at the old price. By throwing in features that customers had not needed at lower price points, The Times had co-opted its ability to upsell those features later.

The Freemium Trap

“Freemium” is generally taken to mean a product which can be used free of charge indefinitely, but which is limited in comparison with a premium version, either in offered features, or capacity (such as storage), or in other ways.

It’s not always a bad idea to have a Freemium model. Particularly, products that provide a long-tail value that is hard to see at the beginning may have to be freemium. Most casual games use freemium these days. Dropbox is also a freemium service, which makes sense, because customers typically don’t have a need to buy up to 1TB of storage in one go- instead, they collect data slowly. Slack is another example: a small team doesn’t always need unlimited message history, storage, and all the bells and whistles on day one.

It’s hard to get someone to pay for something of uncertain value. It’s even harder to get someone to pay for something for which a ready and free replacement already exists.

But on the other hand, many, many startups who use a freemium model shouldn’t. When you provide a product aimed at customers who easily understand the value, and who moreover really need what you offer, then offering them a Freemium experience may simply be giving them a handout. And addicting your customers to the free product can make it even harder to sell the Premium version.

One of our startups, 2016’s Satismeter, experienced exactly this problem. As Co-Founder and CEO Ondrej Sedlacek told me recently:

“Switching from a freemium model to free trial and ditching cheaper plans was a big improvement for us. The truth was that people who needed our product were ready to pay for it.

Freemium ended up being a barrier to selling to some customers, because they would get used to just making do with the free version. When we eliminated our free plan, we saw only a slight reduction in signups, and we increased sales overnight. Plus, free users were ironically the most demanding for support. Paying customers invest their time to understand the product and set up the whole process to get the most value out of it”

Customers who understand your product’s value are inherently better customers in the long run. Attracting people who don’t believe in your product might be necessary at the beginning, but it should be viewed as a means to an end.

Price is about Positioning

In his piece, Whitwell calls attention to this with reference to Apple (itself discussed in another piece: Why You Should Never Ask Customers about Price). When unveiling the iPad, for example, Steve Jobs had basically two options, assuming that he couldn’t actually change the price of the product significantly.

First, he could sell the iPad as an expensive version of the iPhone (something many internet trolls did anyway), or second, he could sell the iPad as a cheaper and better version of a netbook computer. He chose the latter- making a point to talk about the features of a netbook in comparison with those of an iPad, before revealing the iPad’s original price point- at $999.

Voila: the Ipad wasn’t a very expensive phone. It was instead a cheaper and better netbook- one with all the features of an Iphone, and the power of a real computer.

In pricing psychology, this is called “anchoring,” and it’s hard not to notice once you know what it is. Retailers will routinely display their best selling items next to items which are significantly more expensive, and items that are significantly cheaper, in order to give the customer the feeling that she is getting the best deal.

Often products are offered that are far more expensive than is actually justified by features. The logic is plain enough: a few customers might buy the Deluxe Collector Edition, but it’s really just there to make the more popular product look cheap in comparison. That’s how you get a $10,000 Apple Watch, or a fully loaded Mustang Cobra. Buying the next best thing is almost aspirational- the customer is invested in a product category where prices run very high, giving them a sense that they are in the “big game.”

By the same token, restaurants may list the most profitable wine on the menu in second place, just above the cheapest wine, and just below a significant jump in prices. This plays off of a human tendency to “reality check” prices based on other available evidence. $25 for a bottle of wine seems like a lot if the options are $5, $15 and $25, but it seems reasonable if the prices start at $15, and reach over $100.

In sum, pricing can function as a way of positioning a product in the market. Too cheap, and the product may not be taken seriously enough. Too expensive, and it may flash a warning to a potential customer that the product is simply not for them.

Think About Pricing: Cost and Value

There is no formula for pricing. One of the hardest lessons that many startups learn is that the value of a product as they understand it, can be very different from its value to a paying customer.

Thus, cost and value are only loosely correlated. This is why it costs $10 to use the Wifi in an airport. The cost is negligible, but the value to a traveler is worth the price. Most commonly, startups should learn much more about their own customers, in order to understand the value of their products to those customers.

That doesn’t necessarily mean doing what your customers want. But it does mean understanding what your customer’s needs and priorities really are. Anyone who has angrily paid an obscene price for a bottle of water on a train, or for a dongle they simply must have for their Mac, knows that pricing is correlated with need.

Most importantly: think about your pricing more. It rarely fails that, when asked about their pricing, startups lack key insights that would potentially allow them to make the difference between a profit and a loss. Absent a clear picture of the value of their products to customers, startups simply guess at what people will be willing to pay- and more often than not, they guess wrong.

An Exit is Not a Vision

/in Marketing, Starting a Business, StartupYard News/by StartupYardI attended a pitching competition this weekend, as I do many times each year. This one was not unlike many others.

Most of the pitches were very interesting, and I liked many of the ideas. But I noticed something I didn’t like. Aside from the usual little foibles like “we’re the Uber of X” (probably not), and “$400 Billion Market!” (kind of not really), I heard, several times, detailed digressions into exit strategies.

Ok, there’s nothing inherently wrong with thinking about an exit strategy. But I do find something offputting about a company that is trying to raise seed-level investment, talking about selling out within a couple of years. Exit strategy is not part of our program at StartupYard, because an exit is a natural extension of success- it doesn’t need to be the focus.

An Exit is Not a Vision

We like to ask people what they hope their company will be doing in five years. That’s not because we think they really know what will happen in that time (they never do), but because we want to know the scope of their vision for the future.

You should know where you want to be in five years, because if the answer is “doing something else,” then building a startup might not be the best path. This isn’t Wall Street- there are no golden parachutes at early-stage startups.

Which would you rather hear? “I need $300K to build a great company that’s going to be changing the way people do X in five years–” or, “I need it to build a company that’s going to be bought by Google 18 months from now?”

One of those two is a vision. The other is at best a strategy (and at worst a delusion). Again, I’m sure it would be great if a startup could promise it definitely would sell to Google in 18 months, but if that’s your vision, and it doesn’t work (because it probably won’t), what then? If your greatest hope is to cash in a lottery ticket, then what kind of a sales pitch is that?

As Frédéric Mazzella, founder of BlaBlaCar, recently said in his comments for The State of European Tech, by Atomic Ventures, “Growth isn’t like an elevator, it’s like building a set of stairs.” Meaning, every step on the path towards growing a large company has to be taken individually. There is no straight line to the top.

Founders Focusing on Ambition, Not Passion

This is indeed something I’ve been taking more note of recently. It seems to me that I am hearing more about startup founders’ ambitions, and less about their actual passions. I’m getting a pitch about a person, instead of about the idea they care about. The cliche of “make the world a better place,” is at least a nod to social responsibility and building a sustainable business.

But this focus on exits, which I’m sure some startups do in their pitches, seems to me to be crass and opportunistic. Even more perversely, I’ve actually heard this phrase more than once: “I have a passion for growth.” Which uses the words that founders know we want to hear, but is pretty twisted when you think about it.

Maybe this will sound incredibly touchy-feely, but I don’t think the best and brightest would be in the tech business if it was just about the money. Why we have to tell ourselves that it is, in fact, all about money is a mystery to me.

The sad part, at least for me, about such pitches is that they completely alienate me, and I suspect many other investors, and betray a focus on money that is unhealthy for an early stage company, still trying to find product/market fit.

As we say, “If it was easy, everyone would do it.” And yet I notice founders trying to make their paths toward profitability seem easy. A breezy growth spurt, followed by an acquisition, champagne raining from the sky. I suspect though, that this is a combination of self-deception and poseur behavior. Sound like you believe it, the reasoning goes, and the audience will think you have it covered.

But at the end of the day, if it’s something Google is going to buy for a cool $100 Million, they’ll be buying it because doing it themselves is hard. The value is in the difficulty of the work, along with the opportunity it represents. And yet I hear “$100 Billion market,” far more often than I hear: “here’s how we can do what nobody else can do.”

As I sometimes say to startups: “Do you want to be something- or do you want to do something?” Being a hyper-growth startup in a huge market is an ambition. Doing the best work you can, no matter what business you’re in, is a passion.

Ambition Isn’t Enough

Of course, at StartupYard we talk to a lot of startup founders, and many, even most, will never realize their ambitions. That’s not a bad thing. Ambition is important, but it can’t be everything. Sometimes people fail because they aren’t smart enough, or don’t care enough, or don’t have the timing right. But sometimes it’s because their ambitions are far too great for their actual passion.

We’ve seen that first hand, and the end is always the same. The founder who is all ambition does just enough to satisfy the ego, and never enough to really drive the company forward in a meaningful way. Progress, according to ambition, is to be seen as a winner. Passion is for winning- for being the best, even if no one knows it yet.

Ambition is important. You must have it if you want to try to do things no one else has tried. Ambition drives people to succeed. But naked ambition leads nowhere. It must be paired with a strong passion to do good work.

These are hard lessons that must be learned. Still, I wish that as accelerators, incubators, investors, and mentors, we would be more clear on what we value most- which is passionate founders who are ambitious in a healthy way.

We like ambition. But ambition is not ever enough. Ambition doesn’t drive you to do the right thing for your fellow man. It doesn’t make you unique, or creative, or better than anyone else.

Passion is the thing that can’t be taught. You can develop someone’s ambition, and we often do just that. But we cannot develop their passion. As investors, it’s always tempting for us to be sold on a founder’s ambition. But in the end, passion always wins, and our best startups are the ones doing things that only they can do best. Why? Because they love it. Because they couldn’t imagine doing anything else.

And if they make boatloads of money from it, I can virtually guarantee, it will be a side effect of that passion, not a result of their ambitions.

Either you have passion for something, or you don’t. If you’re thinking of starting a business, I can only encourage you: do something you really care about, even if that something isn’t sexy, or isn’t going to make you very rich. If you’re really good at it, then it will make you rich enough.