10 Questions to Ask a Startup Accelerator

/in Life at an Accelerator, Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYardYour Landing Page Sucks (Yes, Still)

/in Marketing, Startup Tools/by StartupYardThe Landing Page. Yes, in 2018, this is still an important part of your arsenal of marketing skills as a startup. That’s why at StartupYard, I still do a full-on workshop on just this topic, and why with every startup we accelerate, we drill these basic themes over and over again.

Why? Because the ability to write and execute an effective landing page depends on a very clear grasp of good marketing in general. A landing page is a “single serving communication,” or a piece of marketing that has to speak for itself, and be judged on its own. So it is also a great testbed for ideas, and seeing what works, or doesn’t work.

Since we face many of the same challenges with startups year after year, I thought it was high time to publish a post about the basic principles behind an effective landing page. These strategies can be used in many forms of communication (like email), because they focus on understanding the *why* of messaging decisions, rather than the *what* of any particular message.

What is a Landing Page?

For the purposes of this discussion, a landing page is a part of your website (or online product) where visitors “land” first. Depending on what kind of company you are, you might have only one landing page: your Homepage. Or you might have many. A blog post can serve as a landing page if it is meant to draw people in via search or social media.

Here are some examples of successful modern landing pages of different kinds. Take a moment and appreciate what about them is consistent and familiar.

In this discussion, we’re going to follow the KISS principle, and only talk about one kind of landing page, which is the single-purpose landing page, with one target audience, one message, and one call to action.

The Trust Pizza

Over the years, I’ve worked as a copywriter on uncountable landing pages, and other single-use marketing materials for scores of startups. I’ve devised a very simple formula for determining whether I am being effective with a particular page.

Content is King, as we say. A great message is most important. But an effective message follows from the right approach. Having a formal structure that is designed to be foolproof is important in helping you shape a message.

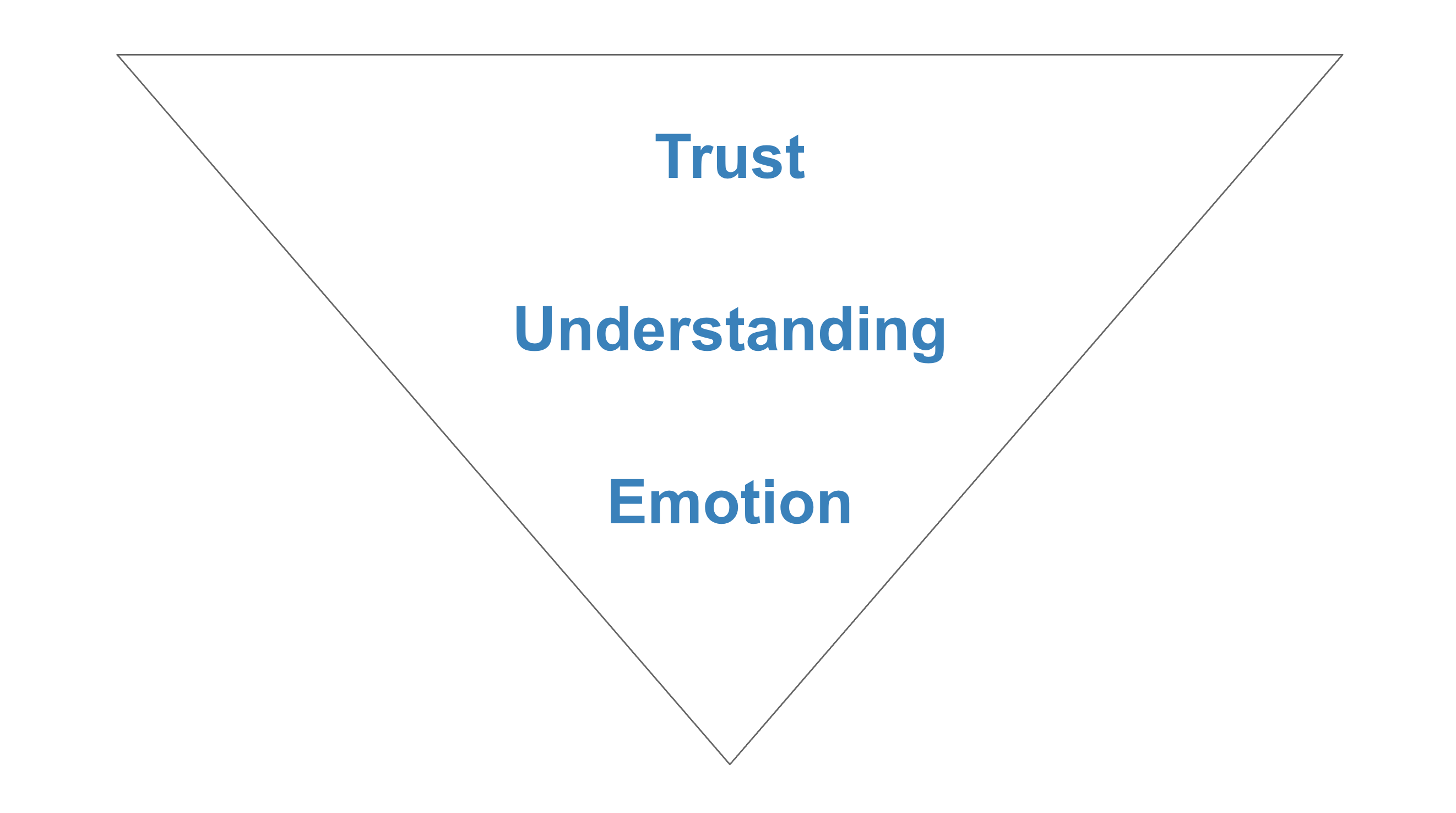

My formal approach is simple. I call it the “trust pizza.” Here’s what it looks like:

What is important about the Trust Pizza is its shape and the order of ingredients. Follow this simple strategy, and you’re much more able to judge whether your landing page is likely to work or not.

-

Trust = Crust

The most boring but essential element of the pizza is the crust. Not only do we grab a pizza by the crust, we also use the crust to judge the pizza overall.

Just think about evaluating a pizza. If the crust is burnt, what does that tell you about the overall quality of the thing? On the other hand, if the crust is soft and inviting, then you know the pizza will probably be good. Looking at the middle of the pizza tells us very little about it: it might be good, but we can’t know.

The “outer layer” of a landing page is just like that. Trust is composed of every background element of your page. Do you have a header and footer? Do you have appropriate links and contact details? Is the font, color and any background image on-brand?

You should spend as much time on these details as you do on the central message of a landing page. These things tell us whether you can be trusted at all, much less believed in this particular case. Get them wrong, and forget about anyone taking a “bite” out of your landing page.

The trust crust also reminds us not to get too clever. At the end of the day, no matter how revolutionary the idea, a pizza still looks like a pizza. So it is with a landing page. The content should be interesting, but not *less interesting* than the format.

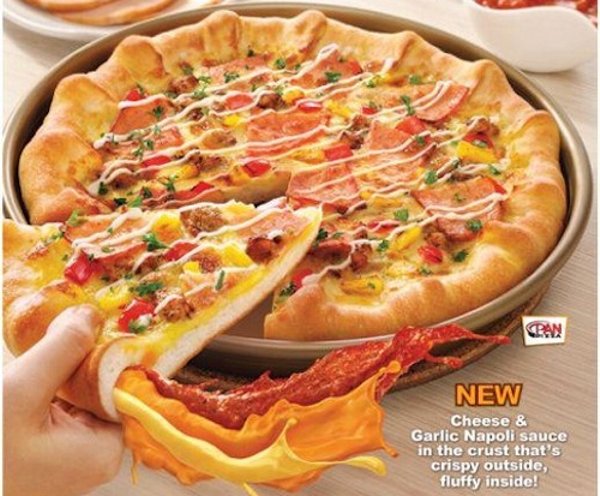

Not only confusing, but actually disgusting.

If you want to give the impression that you’re incredibly hip and modern, do so with the understanding that this may be the only message that gets across. I may admire a pizza shaped like the Eiffel tower, but I don’t want to eat it.

2. Understanding = Toppings

The “understanding” aspect of your landing page is the heart of the message. It is the information you want to convey. It’s often a number or a date. It’s a key point. If a visitor remembers anything about you, it should be this.

Of course when you order a pizza, the toppings are the focus. They differentiate your pizza from all other pizzas. Cheese and pepperoni is totally different from a cream sauce with BBQ chicken.

But remember: an effective pizza has only the right combination of toppings. Go too crazy, and you turn something good into something truly nasty. Burgers are good. Fries are good. Nuggets are good. But all 3 on a pizza are not good, they’re gross.

Adhere to the KISS principle (Keep it Simple Stupid), when choosing your toppings. If you aren’t sure how to blend two ideas together, then don’t try. Choose the most important one, and go with that.

Better a few good toppings than a mess of bad ones, right?

All of these things individually are amazing. All of them together are horrifying.

3. Emotion = The First Bite

Finally the good stuff. The pointy edge of your landing page pizza is the spot at which a customer will “bite.” So you need to give them a good reason to do so. You’ve presented an appealing crust, a nice set of toppings, and now you want a nice, crisp wedge shape to finish the job.

This is the Call to Action. The button, or other cue which should prompt a person to do something (take a bite of the pizza), and be led somewhere else on your website, or in your customer funnel.

The call to action is the simplest but often most important part of a page. It prompts the user with their next move, and at the same time must show them exactly what happens when they click the button, follow the link, or enter their information. The “ first bite” has to be rewarding enough: it has to be mouth watering.

The Pizza Shaped Landing Page

The above is a tool for planning and assembling the elements of your marketing message for a landing page. But remember that just as you must form a pizza from raw ingredients into a certain shape, so must you shape a landing page to be enticing and “edible.”

One of the keys here is “visual momentum,” or what I call the pinball effect. That is, the attention and visual interest of the page should eventually lead down to the place where you want eyeballs to be. It can’t *start* there, but it shouldn’t end somewhere else. No big exciting things to see off to the side. No distractions: just one bigger message leader to a smaller one, leading to a simple action.

In principle, you should try to keep the three key sections of your landing page organized in order of interest:

- The Headline

- The Body (or Subhead)

- The Call to Action

The Headline

The headline, while simple, should grab the most interest from the beginning. It is something bold and maybe unexpected. It is not, I repeat, *NOT* a list of buzzy words like: “Analyze. Evaluate. Innovate.”

That’s just lame folks. Your headline needs to be a statement about why you’re different. It should be something ripped straight from the “unlike” section of your positioning statement. It can even be negative: “Don’t Be Lame,” or “Had Enough BS for One Day?”

That’s an eye-catching statement. Something weak and defensive is not eye-catching. “We Care about You,” is not compelling. “Our Customers Come First,” is an eye-roll at best. Say something definitive about what makes you different, and more importantly, why your customer should even care.

Remember: the Headline is about letting the visitor know what they’re in for. It’s a signal of what’s to come. So it needs to be a strong one.

The Body (Or SubHead)

Here you have the most freedom. It’s toppings time! You should include numbers, or statistics, or outcomes that your product or service will provide. What’s the difference between a pizza you love and one you hate on sight? The toppings.

“Trusted by 3 of 4 Startups,” for example, or “Proven to lower your costs by 30%.” These are informative, direct statements about what the product is promising to do for the customer. They’re beautiful sausage and pepperoni, or olives if that’s your thing.

If the landing page is for an event or a sale, then it might be time to include the date or time.

Remember the It’s Not About You principle. This is not the time to explain that you are a bio-organic-cruelty-free-lactose-intolerant team of albino hemophiliacs who identify as lawn ornaments. The customer wants to hear what’s in it for them. You’re trying to tell them you’re using artisanal cheeses made by blind pagan craftsmen in the alps, but they want to know if the pizza is vegetarian or meat-lovers. They want the facts, not the fluff.

Now is also *not* the time to sell or urge action. Don’t jump the gun here. You’re being informative. You’re showing the meat of the offer, not closing the sale.

The Call to Action (Take a Bite)

Now you’re closing. The call to action is simple but very tricky. You want to accomplish a bunch of objectives at once, to some degree or another. You want the visitor to know a number of things:

- What am I supposed to do

- When am I supposed to do it

- What will happen

- When will it happen

And remember, this is a call to action that may be as long as two or three words. It has to accomplish a lot in that space of time. It needs to rely on context and build upon the preceding elements to do that.

But always consider the call to action in this context: Is it clear to the reader exactly what will happen when they press that button? And is what they think is going to happen the same as what will actually happen? As a landing page is meant to create a relationship, you need to start it off by delivering on what you’ve promised.

Don’t offer something in your call to action that you can’t deliver. Don’t lie. Don’t even get close to maybe being a little bit dishonest. Just don’t do it.

Here are some common “Call to Action Lies” to avoid, along with the reasons they suck:

- It’s Free! [But give us your credit card lol it’s not free]

- Start Your Trial [Actually give us your contact so we can sell you]

- Get it Now [But you have to wait a while]

- Get the Beta [When it’s ready if ever]

- Learn More [Just kidding lol buy now]

Instead, a call to action should do exactly what the user expects. If you want their email, say: “Enter Your Email,” if you want them to buy, say: “Buy Now, Save X.” If you want them to demo the product, then make the demo accessible when you say it will be.

Remember: If you’re thinking it’s a cheat, then your visitor is too. Don’t treat your customers as dumber than you are. Assume they’re smarter.

Stick to the Trust Pizza

Remember, whatever decisions you make about *what* to communicate, never forget the importance of *how* you communicate it. In my experience, more than half of the message is not the words you use, but rather their format.

Does it look right? Does it make visual sense? Is it weird or somehow off? These details make or break a landing page much more easily than a less than perfect turn of phrase. Stick to the pizza. Don’t reinvent it.

The StartupYard Big Book of Marketing

/in Marketing, Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYardThe StartupYard Big Book of Pitching

/in Marketing, Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYard4 Ways To Kick Ass at an Accelerator

/in Life at an Accelerator, Startup Tools/by StartupYardMy job about half of the year is to travel around Central Europe meeting with startups and entrepreneurs, listening to pitches, and scouring the internet for what might just be the next great startup to join StartupYard.

We have a new batch of startups joining us in Prague in just a few weeks, Batch X, which means we’ll be doing this for the 10th time. We’ve seen lots of startups benefit from a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and we’ve also seen others not get everything they could out of the program when they were here.

Sometimes founders tell us what they wish they had known to do before getting here, so in the spirit of that request, here are 4 things any startup can do to kick ass at an accelerator.

You can also read more about the acceleration process in other posts like: 5 Tips to Get the Most out of Your Mentors, 11 Things We Say All the Time to Startups, and 6 Silly Startup Mistakes You Can Fix in 5 Minutes.

One: Know Your Mentors

“Oh hi… who are you?” Is not a question you should be asking the CEO of a major technology company who has taken a day off from a very busy schedule to come and talk to you about your business for no other reason than he or she feels like giving something back.

Certainly StartupYard is selective when it comes to our mentors. We look for humble, experienced, informed, and engaged people with powerful business networks, who generally have enough of a sense of self-worth that you don’t need to suck up to them. Still, there’s a world of difference between being a kiss-ass, and not knowing someone’s name or where they’re from before you meet them.

Your attitude as a founder in any accelerator program should be: “I have limited time with these resources, so how do I maximize my use of them?” Being with a C-level executive of a major corporation, or with the managing partner of a VC fund, or with a successful startup founder for a mentoring session is like the intellectual equivalent of being left alone in a bank vault. You should really spend your time going after the important stuff.

What important stuff? What is this person’s relevant experience in my field? What connections do they have that could save me weeks or months of waiting for cold emails to get answered? What do they know that I don’t? We say you should try and treat mentors as potential customers, and that’s true as well, but just as with a customer, most of that communication should be you learning from the mentor, not you spending the mentor’s time trying to convince them of your vision.

Wait, what am I saying? Don’t try and pitch the mentors your ideas? No, of course you should do that, but many founders get carried away with this. A mentor hears your pitch, raises a few objections, and before you know it, the whole session is taken up with the two of you in a battle of wills, one trying to convince the other of their rightness.

You know who loses in this situation? You do, because the mentor has nothing to prove. They’ve already had impressive accomplishments and success along the way. They have no pressing goals in their meeting with you. You have goals, so spend your time finding ways the mentor can help you meet them.

That means knowing as much as you can about the mentor before the meeting. Ask the management team about them. We know the mentors. Check out their companies and their profiles on LinkedIn. Get an idea of what you think they can do for you before you sit down and ask them for help. Help them help you, as we say.

Two: Know Your Numbers

Below I’m going to share with you a number of real life #epicail scenarios for founders who have been with us, sometimes for a full 3 months, and have not managed to quite grasp this essential lesson: Know Your Numbers.

- So how many email subscribers do you have right now?

- Uh.. i would have to ask the marketing guy…

- Do you have over 1000?

- It could be…

- Over 10,000?

- Probably not…

- Do you have any idea?

- No…

- What’s your runway?

- Well, we have XX Euros in the bank…

- So what’s your runway

- It’s… if we spend it slowly then it could be….

- Ok, hang on: What is your runway at the current burn rate

- Uh… I have to ask…

- You don’t know.

- I don’t know

- How much are you raising?

- It depends how much we can get….

- How much do you want to raise?

- As much as we can get…?

- Yeah, no.

This is about two things, mainly. First, it’s about answering questions as straightforwardly as you possibly can. This means yes or no questions have yes or no answers. Do you have cash for the next 6 months? Yes or no. Of course it’s never that simple, but when a mentor or an investor or a stakeholder is asking you a question like this one, they want a straight answer. If you need to qualify, ie: “yes, but…,” or “no… if,” that’s totally fine. Yes and no are powerful words, which is why founders so often try to avoid them.

The other, related thing some founders try hard to avoid is real numbers. Real numbers are your friend! How much money do you need to raise? “Well… we could get by with around…” No. Start with a round number: “We need to raise €150K for runway for the next 12 months.” Again, you can qualify these answers later, but if you don’t start with something real, then there’s no way for anyone asking the questions to understand what neighborhood they’re even in.

Just giving straightforward answers, with the understanding that you don’t have to know every answer precisely every time (though it helps if you do), we can see these conversations going a bit better:

- So how many email subscribers do you have?

- Last I checked it was between 2000-2500, but I would ask my marketing guy for an exact number

- Great! That’s more than I was expecting

- What’s your runway?

- It’s 6 months with our current cash burn, but we can sustain ourselves if we go lean and cut costs.

- Ok, how much would you have to cut?

- About 50%. We are covering half our burn rate right now in net income

- Ok, thanks for the info

- How much do you want to raise?

- We want to raise €300k in a seed round. If we can’t do that, then €100k in an angel round will be ok for the next 9 months

- Great, let’s talk about your strategy

Those conversations are so much better than the initial ones, right? The truth is, you don’t even have to know a lot of your numbers with great precision. You just have to know what they should be, and what they are not likely to be.

How many email subscribers do you get in a week? Most founders don’t know that to an exact figure, but they should have enough of a finger on the pulse to be able to estimate: if it’s been 10 a week or so, and the last time you checked was last month, then there are probably 40 more than before. It bears checking, but it’s a best guess. It’s an answer, which is better than “I would need to check on that, because I have no idea.”

A lot of numbers questions are asked with the understanding that your answers will be either guesses or estimates. Runway is only semi-concrete. It’s an estimate. Number of downloads is concrete, but again, the exact figure is less important than the ballpark. The amount of money your raising is understood to be a goal, not a figure set in stone, but you have to have an answer to that question that sounds reasonable and compares favorably with the reality.

The simple fact is that often times, founders just don’t study their numbers closely enough. They don’t work enough in spreadsheets and they don’t work enough on contextualizing, for themselves and for those around them, what their numbers and metrics mean, why they are important, what they are, and what they should be.

Anyone might have a difficult time answering “what will your cash flow situation look like in month 15 of your financial projection?” But on the other hand, I should know if I’m going to be making money or losing money at that point. A familiarity with my own numbers saves me from the embarrassment of not knowing this basic fact about them. “I’m going to be making net profit at that point, but I think less than €10,000. I need to check it.” That’s an answer we can work with.

Three: Know Your Deliverables and Your Schedule

Investors, including accelerators like StartupYard, manage their relationships with portfolio companies in ways that are quantifiable and hopefully easy to chart over time. We need data from our startups, and we need to know, within reason, that startups are working on the things we need them to work on. It’s not that investors should run a company, but rather founders should be given certain clear hurdles that they need to meet to satisfy our relationship. This is mutually beneficial, if done correctly.

For example, early in our cooperation, during the acceleration phase, we will have a lot of “deliverables” which we expect founders to work on with us, and to have done by a certain time, to a certain standard.

Examples are things like a website, media kit, business plan, user projections, market overviews, competitor analyses, and so forth. Later it’s a pitch script and a slide deck for Demo Day. Then maybe a one-pager for investors. Years after the program, it may just be basic financial data every quarter. Deliverables at the beginning can be quite big and important items, and deliverables at later stages can be less all-consuming or critical, but they are still deliverables. They still need to get done.

A deliverable that doesn’t seem important to you might be very important for the other party. At least knowing this, and knowing why, is going to help you get much more out of an accelerator. You may find what you didn’t value before, when properly explained, is more valuable than you first thought. It can be the difference between something feeling like homework, and something feeling like it will really help your company move forward.

A big challenge for some founders is to understand that when you are dealing with outside advisors and investors, you are dealing with someone else’s standards of what constitutes “finished,” and “acceptable.” Hopefully, in the best case scenario, this is because the advisor or investor has a bit more experience than you do about what level of work you should be delivering, which is why the item is something they are interested in seeing by a certain date.

The deliverables should be helpful to you. If they aren’t, then there’s something wrong.

At StartupYard, for example, we don’t wait until the day we announce the names of our latest batch of startups to make sure that they all have working websites. These are deliverables that come up weeks before that time. We do this because we know that the odds are good that we will not be happy with the first version, and we want there to be time to change it and improve it.

We only do that because experience tells us it is usually necessary. If it weren’t necessary, we wouldn’t do it.

A later investor might not expect this kind of hands-on access to your work, which is clear to you only if you know what your deliverables for them are. This can mean going out of your way to make sure you know exactly what is expected of you, because that might not always be clear. It’s ok to ask what people expect, and it makes your life easier. You don’t want to be caught out the day before your product launch by an investor suddenly demanding that you change your website. You want to know whether that’s something the investor will want some control over.

For example, you can end meetings by saying: “ok, so if I understand correctly, you want to see XYZ, with these details, by next wednesday, and then a final version of that the next week?” This is getting to know your deliverables. It’s much better than just saying: “oh, we need a website? Ok, I’ll get it done pretty soon.” What does it mean to get it done? What is soon?

Discussing your deliverables also allows you to shape them in a positive way. You may not believe a later investor needs to sign off on some aspects of your work. That’s something to make clear beforehand. You may decide together that a particular deliverable is not needed, or a particular schedule is too ambitious.

A major frustration for an investor or advisor who is trying to help a startup to meet a high standard of excellence is to not have the founders take these deliverable schedules seriously. These schedules are in place (hopefully!) for a good reason, and though it may not be one you necessarily agree with all the time, it serves as a fundamental basis of our relationship. This is how we understand if we are being helpful to you or not.

Four: Use Your Management Team

(Half of) The StartupYard Team

Hey, we’re people too! Each of us has particular skills and particular strengths. If you don’t know what we’re good at, then it’s hard for us to be good at that thing on your behalf.

Remember the axiom: “if you don’t ask, you don’t get.” The management team of the accelerator is there working for you. If the organization is well run, and the incentive structure is set up correctly, then the management team should be interested in making portfolio companies more valuable, founders happier, and products and services better. That’s why we exist, and it’s our main role with our member companies and alumni.

The acceleration process does create a certain sense of whiplash, particularly with a very hands on program like we have at StartupYard. We are so hands on from the beginning that when we start to pull back and let founders steer on their own, they can and sometimes do feel like we’re “letting them go,” or distancing ourselves. Like we don’t care about them anymore, or that they’re “on their own.”

Of course we don’t want that, but the relationship has to change from “push,” to “pull.” Instead of the management team looking over the shoulders of founders, founders exiting the program or even years out have to reach back and ask for our attention if they need it. In my time at StartupYard, I’ve helped to accelerate nearly 50 companies. I can’t spend my days checking up on 50 different founders and seeing if they need my help. They have to come to me, but some never will, even if they need help.

I know this because when I do happen to be talking with alumni founders, it’s a rare instance when it turns out that they haven’t needed help from the management team at some point since we last spoke, and still failed to ask for it. They’ll say: “I didn’t want to bother you… I should have called.” Well, yeah, you should! Some of the best performing startups in our portfolio use us the most. They get that attention just because they ask for it.

2 Mental Tricks That Will Make You a Better Entrepreneur

/in Starting a Business, Startup Tools/by StartupYardThis week at StartupYard, our current batch of companies has been in the tall weeds trying to finalize their marketing and messaging for our press launch, which went off last week.

The cliché expression for the feeling they are experiencing is “jumping off a cliff and building your wings on the way down.” A version of that quote is often attributed to Reid Hoffman, who uses it to describe entrepreneurship generally. In fact, the quote originated with the science fiction author Ray Bradbury, in a review of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C.

In a way that makes much more sense. The quote describes inventiveness and forced creativity. It can be the realm of the entrepreneur, but it is more generally the realm of anyone creative.

The reason I mention this is that a founder can be both very strong in creativity, and still very unconfident in their ability to creatively communicate with customers. That’s what my job with them is all about.

Creativity and Empathy

This week I’ve done two workshops with our startups. One on “Storytelling,” and the other on “Customer Personas.”

To me these are essentially the same topic. Stories are the way that the human mind invents and creates the future, and how we understand our past. It is about how every “character,” or person undergoes an arc, and how those arcs interact and impact each other. Building personas, in the way I see it, is how we examine our assumptions about people, formulate tests of our insights, and discover ways to empathize with and understand those who use our products.

Here we’re going to talk about some simple mental tools that are going to help you ideate and test your own assumptions about your customers, in order to better serve and sell to those who need your products most. In many ways these will not be unfamiliar concepts, but to the mind of an engineer or a maker, they are often mysterious and elusive in terms of application, particularly when it comes to marketing.

I’ve written a number of posts on this topic, so I encourage you to start with these. Go on, I’ll wait.

…

Double Loop Learning

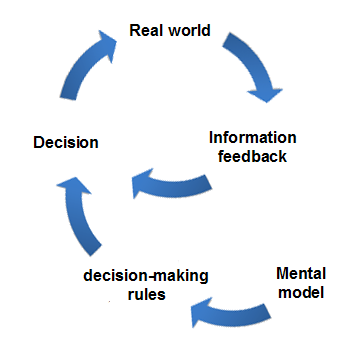

Double loop learning is a basic model for creative and flexible thinking. In essence, it suggests that there are two ways to approach the learning process (such as in product development), a “single loop,” or a “double loop” process.

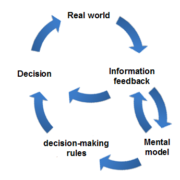

Here is how they look:

In the Single Loop Thinking:, you begin with assumptions (a mental model), logically leading to a set of rules, which lead to a decision. From there, you adjust your decision based on feedback.

In Double Loop Thinking: You do the single loop, but at the same time, you go back to the initial assumptions and adjust the mental model, which may cause you to adjust the rules, and not just the final decision.

Example of Single Loop: In deciding on buying a car, I imagine the car I want to buy: Color, Type, Make, Model. Using this model, I decide which dealership to go to, and how much I can expect to spend (making rules). Based on this, I decide on a dealership. Now I go to the dealership, and I find out if I can get the deal I want for the car I want. If I can’t find the car, I go to another dealership (information feedback to decision).

Example of Double Loop: I do all of the above. But I also ask myself: should I be trying to buy this type of car? Were my ideas realistic? Based on what I learned from my visit to the dealer, what other cars got my interest, and might be better for me? I adjust my expectations, and make a new decision about the kind of dealer I need.

Why it Works:

Single loop is in fact the way we are taught to learn in school. We are given rules, and told to apply them continuously, looking for the correct decision given the stated rules. Just think of all that math homework you had to do.

That kind of singular repetitive learning works most of the time, particularly when a desired outcome is pre-determined. However, this can also lead people to forget that the initial mental model may be flawed, particularly after gaining real experience with it.

The most typical case in startups, is the startup that makes some early decisions about who the customers were and what they wanted, but never came back to those assumptions, and ends up serving a smaller niche than necessary, because all their later decisions are based on data they’ve gathered so far. The longer a company remains in this “single loop,” the less likely they are to challenge their original assumptions and thus be able to successfully pivot to a new market.

Here is a concrete example using a classic business case many people face even as kids:

Single Loop:

1. I decide to sell lemonade. I choose a location for my lemonade stand and a price for the lemonade, based on my intuition about what people will pay.

2. I observe the sales cycle. How many people visit, and how many people convert to buying a lemonade.

3. I slightly adjust prices and location to optimize my sales.

4. Go to 2.

Double Loop:

- I decide on a location for my lemonade stand and a price for the lemonade based on my intuition.

- I observe the sales cycle.

- I slightly adjust prices and location to optimize my sales.

- I re-examine my initial strategy, and try a new location, or even a new product (maybe ice cream?)

- Go to 2.

The OODA Loop

Ok, maybe running a startup isn’t exactly like flying a combat mission in a $50m fighter jet in the U.S. Airforce. Still, you can learn from the mental training that fighter pilots, spies, and military strategists use on a continuous basis – often minute to minute.

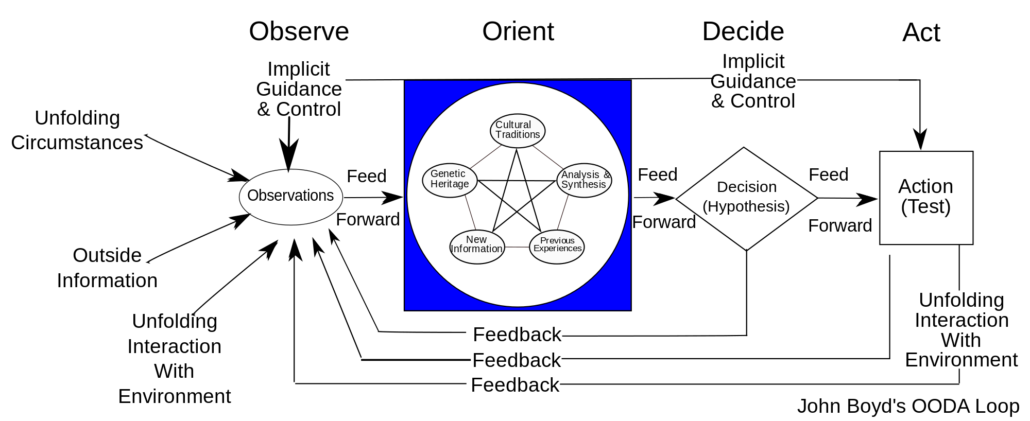

It’s called the “OODA Loop,” for Observe Orient Decide Act, invented by Air Force strategist John Boyd, called by some “the greatest military thinker no one ever heard of.” Here is a very thorough explanation of the general philosophy behind it, written for a popular audience. In as simple terms as possible, the OODA Loop is a mental tool which forces its user to continually adjust their future expectations, based on current realities.

Why it Works:

The OODA loop is a tool for forcing oneself to continually affirm their past decisions using current information, and to drop previous assumptions and goals based on current circumstances. The OODA loop is used as a mental tool to keep you focused on the current moment, and what is happening around you, to avoid sticking to a strategy which is not working, and to continually notice new opportunities.

Boyd’s central thesis has become a core principle of modern warfare, and a frequently used technique in sales training, and even by professional chess players. The core tenet is this: the mental models one holds tend to lose their usefulness in chaotic situations. Therefore, updating our mental models, or “orienting” our expectations can help us to make better decisions for any given situation.

What does that look like practically? I’ll refer to a thought experiment that Boyd himself proposed:

“Imagine that you are on a ski slope with other skiers…that you are in Florida riding in an outboard motorboat, maybe even towing water-skiers. Imagine that you are riding a bicycle on a nice spring day. Imagine that you are a parent taking your son to a department store and that you notice he is fascinated by the toy tractors or tanks with rubber caterpillar treads.”

Now imagine that you pull the skis off but you are still on the ski slope. Imagine also that you remove the outboard motor from the motorboat, and you are no longer in Florida. And from the bicycle you remove the handle-bar and discard the rest of the bike. Finally, you take off the rubber treads from the toy tractor or tanks. This leaves only the following separate pieces: skis, outboard motor, handlebars and rubber treads.”

The thought experiment then asks us to orient to this new situation by putting all the elements together, not in reference to how they were introduced, but rather only focusing on what the elements themselves are, or can be.

You are on a ski slope. You have skis, you have a motor, you have handlebars, and you have rubber treads. What’s going on?

Spoiler: You’re on a snowmobile. That’s what’s happening. Nothing you learned to this point other than those facts matters. To master the OODA loop, you have to be able to clear your mind of these details when they are no longer useful.

The OODA loop focuses on observing the current situation, combining that data with experience and knowledge, and making a decision focused on what is happening right now.

Actually we are quite familiar with elements of the OODA loop in pop culture. Films like The Bourne Identity, or the recent Bond films show classic outcomes of the use of OODA loop, which is the result of real special operations personnel training the actors and consulting on the scripts and fight scenes.

The tension that arrises from these films, in which we observe someone using the OODA loop, comes from the audience being slower to understand how the protagonists are processing situations. As an audience, we have a hard time dismissing details and living in the moment, so it is exciting to see characters who are unpredictable, and yet acting very logically.

This scene from The Bourne Identity is a classic example of the OODA loop in action.

Here’s another from the classic film Top Gun, handily labeled so you can follow the steps that the fighter pilots are using. This video has an added bonus in that Maverick, played by Tom Cruise, fails to use the OODA loop, and suffers the consequences.

The Monty Hall problem

The OODA loop is a practical tool in decision theory. Probably the most famous case of a practical application is the so-called “Monty Hall Problem.”

The problem was first articulated in the 1970s in response to an American game show called “Let’s Make a Deal.” The problem goes like this:

“Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?”

What’s important here is differentiating between a decision strategy, and a single decision. While the chances of the original choice being correct are indeed ½, the odds that the initial choice would be correct over many iterations are only ⅓. That means that if you consistently stick to your choice, you will only win ⅓ of the time, whereas switching will give you a win ⅔ of the time.

Why?

Think of the problem again, but with different numbers. Suppose there are 100 doors. 99 with goats, and 1 without. Now suppose you picked a door, and the host them revealed to you all 98 other doors with goats behind them. Now do you switch your choice? Whereas your initial choice had a 1/100 probability of success, your new choice, has a much higher probability. This time it’s 99/1.

If you don’t believe me, you can actually test the phenomenon here.

Applying the OODA Loop

Now that we see the difference between decision theory and probability, we can begin to understand better how the OODA loop works. Because it requires that we observe according to the latest data, we begin to see that applying decision theory in real life becomes more practical.

Take this situation:

You walk into a bar, and observe a group of large men in military outfits standing at the bar. The men are sweating profusely and breathing heavily. No one speaks. You see that all of them are carrying rifles or pistols. They appear not to notice you.

Your observation moves to orientation: your judgement says there is probably trouble. Based on the available data, you decide that turning and walking out will draw attention and cause them to panic, or even attack you. Challenging them is too dangerous, as you are alone and unarmed. You decide to continue past them to the bathroom, where you know there is probably an exit.

You get out of harm’s way and look and listen from safety. The men stand quietly. Eventually a bartender appears and they order beer. The men begin to laugh, and one of them explains to the bartender that they are just coming back from a game of airsoft.

Orientation Leads to Better Decisions

Notice first of all that observation and orientation happen always before a decision is made, or an action taken. The decision is then subjected to another round of observation, where the first set of data are taken together with the new set.

We see from this example that quick reactions are, over the long run, less important than correct decisions. Anyone who has been trained to drive a car in mountainous areas has probably been told that the best decision when a deer runs across the road in front of you is to hit the brakes, but not to turn. This is not because turning is unlikely to help you avoid the deer, but rather because swerving away *is* more likely to cause you to crash the car (possibly into another car).

Those with relevant experience know that the deer will mostly likely run away if you slow down but don’t turn. If you turn, the deer can become confused and may hold still, causing you to hit him anyway. Even if you hit the deer front on, this is less likely to endanger your life than a side collision or losing control of the car. Either way, your best decision is not to turn: no reaction is better than an overreaction.

If in the former example of the OODA loop in the bar, you had reacted as quickly as possible to the situation, you would have made mistakes. First of all, you would have suddenly run out of a bar that was perfectly safe. Or worse, you might have attacked a group of men who were armed.

If you had challenged the men, you might have been killed, or beaten. If you had run out, you might then have called the police, causing further trouble, and perhaps even unneeded violence. If you think that’s overselling it, keep in mind that police shoot civilians with distressing regularity, in some countries, for such offenses as holding a mobile phone, or a toy gun. That often occurs because the police are not trained properly – such as with the OODA loop. Your effective use of the OODA loop could prevent that from happening.

Thus, in this situation, a slow reaction was preferable to a fast one, which is why you made a conscious decision to continue to the bathroom, rather than to engage with a situation you didn’t understand yet. You then moved back to observation and orientation. Discovering that the men are just coming back from a game, you may decide that no further action is necessary. If the new situation, by itself, does not appear dangerous, you may then decide to dismiss your concern, or you may decide to continue to observe.

OODA for Entrepreneurs

As Malcolm Gladwell points out in his book Blink, which explores decision loops in human interactions and business, as well as in historical conflicts, an ability to continually orient to one’s current circumstances is the greatest predictor of failure or success- a predictor more powerful than numerical data or objective observations.

Consider how this can be applied in the thinking of a small business. In the fact of numerical advantages, or sudden threats (such as bad PR, or even a troll on twitter), to what degree is your decision making purposeful, and designed to accomplish a known goal? Are you capable of altering your strategy to take advantage of new information and new events?

Observing new facts is easy to do. But consciously challenging an existing mental model is much harder. Reacting to data only after deciding *how* to react, can make the difference between a major gaffe, and a well-handled situation. Those who are able to act according to the most relevant information in any given moment are likely to win in the long run. Just as in picking stocks, or playing poker, success is found in not allowing your initial strategy alone to determine your future actions.

As John Boyd himself put it, to paraphrase: “in any game, the winner is most likely the one that can orient to new developments and alter their decision making as a result.”

StartupYard is Accepting Applications for Batch X: Automation, Blockchain, and the Future of Work.

Peter Cowley: How to Talk to Angels

/in Startup Tools/by StartupYardRecently I got an email from my friend Peter Cowley, director of the UK Business Angel Association and the Cambridge Angels. Peter has been in tech for nearly 40 years, starting over 10 companies. In 2014-15 he was named UK Angel of the year for his investments in early stage companies. So when he writes down advice about angel investing in his newsletter from the Invested Investor, I pay attention.

Back To the Email. It’s clear Peter had had one too many poorly executed sales pitches lobbed his way that week (he was about to go on holiday he told me later), so he sat down to sketch out some ground rules that startup founders should seriously consider following. I’ll post them below with my comments. Any bolding is mine.

Don’t Call Me, I’ll Call You: No Cold Intros

Advice to entrepreneurs – do you like being called up by a passionate salesperson on your personal phone? If yes, you’re lying. It is a no. I am not saying that you shouldn’t approach angels, otherwise we wouldn’t be able to help you, but I want to give some of my own views on how best to approach us, or at least me!

It is always better to receive a warm introduction than a cold one. This can be through another entrepreneur, another angel or even friends or family. An angel group is a great way to find angels. Have a look for deal ‘sorcerers’ or gatekeepers for the angel group from which you’re seeking funding.

Cold introductions can be extremely annoying. Phone calls definitely don’t work for me, LinkedIn is nearly as bad, direct emails to me will be deleted, unless you fit in with my criteria and have followed the instructions on my website. Cold emails can be sent to angel group gatekeepers. Attempts have been made through social media, but they rarely work.If you can’t leverage your own network to reach the right person, then look at that person’s own network and work from there. There’s nothing worse than getting a cold email from someone who didn’t need to do it that way.

Paradoxically, strangers will always be more willing to help you connect with someone else, than they will be to help you directly. You might call this the “someone else’s problem,” effect. You can use this to get your message to the right person by giving someone else in their network a chance to feel or seem useful and informed, ie: “Dear x, I’m writing you for advice because of your deep connections with StartupYard…”

Use the GateKeepers

Accelerators and incubators are a great way to build connections. Many angel groups and some angels are known by accelerators and incubators, so joining one will ensure warm introductions. Accelerators and incubators offer advice and mentoring and it is positive that you’ve gone looking for that already.Angel group gatekeepers are the main way into the group. You can usually go cold through a group website, and this may work for some groups, but I like to see the entrepreneurs seeking out the gatekeeper first (becauseor better seeking out an angel).

First impressions are paramount to the relationship, so make sure you are approaching the right person. I list my investment criteria on my website, and I know the vast majority of angels don’t, but this will help save time for entrepreneurs and angels. As an entrepreneur, don’t be too pushy but do show the boldness to approach me with something, that will interest me.

This may sound like a lot to think about, particularly when you have such an incredible idea. But, angels hear from so many entrepreneurs. Save yourself time and effort, as well as ours, by doing thorough research before any approach.

This cannot be emphasized enough. We have it as a mantra that “You are Only Ever One Email from a Major Breakthrough.” That does not mean you should send 1000 emails today before lunch. It means that the right email, at just the right time, can make all the difference.

It’s a continuing shock to me how few startup founders bother to do basic research. And I don’t mean googling us and finding out we’re an accelerator. I mean reading what we’ve written, looking into our network, finding common connections, and even coming up with questions you want us to answer about ourselves.

I can tell you I’m maybe 10x more likely to answer an email from someone if the email contains a thoughtful question or two. That could be about our program or about something else relevant to what we are interested in and what we talk about publically. Engagement feeds engagement. Once you start talking with someone, they come to see you as a person, not just an email notification.

Yet few founders (other than our own alumni, who are wiser) use StartupYard as the gatekeeper we are. It’s as if we’ve left a rolodex on the table full of choice contacts that startups desperately need, and they’re just walking right past it.

The best are where the entrepreneurs have researched the members of an angel group (not all members are public) and then approached one, asked for help, listened, and then that angel introduces the startup to others. The simplicity of this approach misses many founders. Instead of compiling a list of targets and sending them all a call to action, or what we might call “the numbers game,” a wiser founder bites around the edges of a network looking for a way in. The key here is to establish one contact at a time and actually listen to what they have to say, and act on it. If you were to email-blast a whole list of people at once, you’d then have burned your bridges if one of those people suggested introducing you to one of the others. Instead of “oh hey this startup seems interesting for you,” it’s “oh, yeah I got the same spam as you did.”

Be Bold… But Follow the Rules

In a follow-up email, Peter wrote this, which I think is worth highlighting: One of the advantages of my published criteria is that many opportunities never get to me, and when they arrive by email, several answer my criteria, or point out which criteria they don’t meet.The worst examples are people approaching me after an event where I have spoken (and where my name is on the programme), having done zero Due Diligence on me and then wasting my (and their) time when there are others waiting to speak to me. I’m sure my firm rejection must seem rude to some.Peter mentions this page which contains detailed criteria on investments he is interested in. What is important to note here is that he makes clear he welcomes contacts from people who do not meet the criteria. The important point is whether or not a startup knows they meet the criteria or not. We have much the same attitude. When a founder emails StartupYard aware that some aspect of their business puts them outside our immediate scope, then we can at least have a conversation about how we can help them despite this fact. If instead the founder simply reaches out without acknowledging this problem, our immediate response to just say no. The person isn’t paying attention to begin with. If the investor has to start out their reply by saying: “we can’t move forward because of X,” then you’ve guaranteed yourself a no. On the other hand, if you’ve covered that objection already, then the investor must at least think a bit more deeply about the opportunity. They can still say no, but acknowledging how you do or don’t fit into someone’s criteria can turn a hard no into a soft one. Maybe you don’t meet the criteria right now, or maybe the criteria aren’t as relevant in your case. You can’t have that discussion if you don’t know what they are to begin with. More About Peter Cowley

Peter Cowley, a Cambridge university technology graduate, founded and ran over 10 businesses in technology and property over the last 35+ years. He has built up a portfolio of over 60 angel investments with 3 good exits and several failures. He is the WBAF Best Angel Investor of the World and was UK Angel of the Year 2014/15. He has mentored hundreds of entrepreneurs and is on the board of eight startups. In 2011, he founded and has since run Martlet: a Corporate Angel, investing (currently £5+M) from the balance sheet of Marshall, a £2bn revenue Cambridge engineering company. He is chair of the Cambridge Angels and is a fellow in Entrepreneurship at the Judge Management School in Cambridge. He is a non-executive director of the UK Business Angel Association and on the investment committee of the UK Angel Co-fund. He has also had 16 years’ experience as chair, treasurer and trustee of the boards of seven charities and is voluntary equity finance chair for the Federation of Small Businesses. He is sharing his and others’ experience and anecdotes of angel investing by publishing online and offline – see www.investedinvestor.com

The Worst Term Sheet We’ve Ever Seen

/in Startup Tools/by StartupYardLast week we talked about what makes a startup investor “Founder Friendly.” While that’s important to know, it won’t help startups much if they aren’t aware of what the opposite case looks like: when is a term sheet definitively unfriendly to founders?

With this in mind, we polled a collection of investors and lawyers who are friends of StartupYard, and they shared examples with us of the worst term sheets they’ve ever seen, and what was wrong with them. This post should serve as a handy guide to avoiding the worst terms out there.

Too Much Too Early

Several of the respondents noted problems with a company’s early stage valuation, along with protections for both founders and early investors, as a key problem in later rounds.

Chris Kobyletcki, Innovation Nest

“I think it can go both ways. We see investors not taking into account founders for the later-stage investments. Investors take 30-40% of the company at a super-low price that will not leave space for someone new to join the cap table.

The other case is having a super high pre-money valuation that will result in a company not being able to reach the next level of valuation for the next fundraising. I saw multiple cases of rounds falling apart because of that. “ – Chris Kobylecki, VC, InnovationNest

Tytus Cytowski, Cytowski & Partners

“At the Angel Round stage, I have seen CEE angels ask for and receive a board seat, pro rata rights, drag along and protective provisions, which are typical for the series A stage. In general angel should only receive equity without any special rights unless they provide significant assistance to the startup. I have also seen CEE angels and VC investors take up 20-25% of the cap table in exchange for €200K at this stage.” – Tytus Cytowski, Cytowski & Partners

Peter Cowley, Angel Investor

“At the very early stage (ie seed, seed+, A-) sophisticated angels in the UK always offer ordinary shares that are identical to the founders, with no prefs, and no special rights attached to the shares. We do however drag/tag along, pre-emption and other rights and a number of consent rights – see my own term sheet, that I use as the basis of negotiation with founders. This is more a checklist with my suggestions of how the legals should be worded and I am 100% wedded to little of this.” – Peter Cowley, Angel Investor

Cap Table Headaches

Another hot-button issue is the cap table, where founders and investors make mistakes that cause them future problems.

Jaroslav Trojan Equus Ventures

“The most usual scenario is that investors take majority ownership thinking they can ‘control’ the startup. Most of the problems relate to cap table I would say. Also, too many conditional investment tranches are quite a frequent mistake. I also occasionally hear that startups and investors don’t use term sheets at all which may lead to poorly managed round, confusion, and increased legal costs.” – Jaroslav Trojan, Equus Ventures

“One [item I insist on] that strongly surprises founders is reverse vesting, until I have explained to the founders that if one of the founders leaves the business (I have had to negotiate this three times) then their unvested shares are then available to strengthen whatever senior hires are needed to replace the founder If those shares are not used, then the remaining founder owns a bigger share of the pie.” – Peter Cowley

Planning Your Exit

A theme that also emerged in the responses was that founders and investors often fail to plan for the eventuality of an exit, and prepare themselves legally and practically for the eventual sale or liquidation of the investment.

Investors can and do take advantage of the smaller legal resources and lesser experience of startup founders.

“In later stage investments, the big one to watch is (participating or not) liquidation prefs, which if everything goes well, will appear toothless, but if something goes wrong… I was not an investor but there is a 10 figure exit in Cambridge where the founder (having been on the journey for a decade) was squashed to zero by the prefs.” – Peter Cowley

“In a Polish seed VC deal, I saw participating liquidation preferences set at X 2.5 with the preference participating again after payment to founders from the exit. In another deal led by a Polish VC I saw a VC insert a participating liquidation preference while the term sheet called for a non-participating liquidation. In investment agreements I have also seen liquidated damages if founder stops working at the company and/or decides to leave the board of the company. Liquidated damages started at €50K and went upto the size of the round. Standard terms like drag and tag along are often drafted excessively in favor of VC investor.” – Tytus Cytowski

Some less-than-friendly investors can get extremely creative in the ways they ensure they profit most from a startup’s success. As in the above examples, what can appear to be fair on paper can end up costing a founder any chance of profiting from their own work.

To provide some context, a liquidation preference is a clause in an investment contract which ensures that a certain investor receives the profits from any sale of the company first, up to a certain multiple of the original investment. This means that not only does an investor get their share of the company when it is sold, but they may also get more than their original share if the company is sold for less than expected.

For example, if a VC invests €1m at a €4m pre-money valuation, their stake is 20% of the company post-money (€1m out of €5m). If there is a liquidation preference set at 3x, that means that the investor expects to be paid back at least €3m no matter how much the company eventually sells for. If the company sells for €3m, then the VC would take the whole amount, and the founders would have nothing, even though they’d built a company worth €3m.

Often these issues arise because the founders believe that their companies will be worth much more at exit than ends up being the case. A high liquidation preference is not important if the company is worth even more than the multiple of the preference. But if the company sells for less than expected, the investors can take a huge piece (or all) of the proceeds.

Business Culture: Legal Fatigue

One of our own favorite startup lawyers Tytus Cytowski, who has supported our alum Gjirafa Inc. in fundraising, pointed to our regional business culture as an issue:

“Three big picture problems that translate into specific terms. First, CEE investors focus on maximizing control instead of focusing on wealth maximization. The focus on control maximization is a CEE cultural issue caused by lack of trust in entrepreneurs, corporate mentality of investors and the fact that the main LP of the majority of CEE funds is the government.

Silicon Valley on the other hand focuses mainly on wealth maximization and invests with a ‘spray and pray’ mentality. Silicon Valley investors are interested in absolute returns in portfolio, while CEE investors look at returns on the level of each company. The control maximization problem is especially problematic in deals with Polish VCs.

Second, most of the CEE investors have a strong private equity/investment banking background, which does not work well in the startup world. For example, PE/Investment banking is focused on generating fees and strictly growth metrics. Good VCs invest with an understanding of technology, disruption and innovation, not only growth metrics.

Finally, a lot of CEE investors don’t have experience as entrepreneurs and don’t understand the life cycle of a startup and what terms are crucial at each stage. Paradoxically CEE entrepreneurs that become VCs tend to have the most unfriendly startup terms from my experience. In general CEE term sheets are heavy on protective provisions (veto rights), liquidated damages and penalties for founders, drag and tag along, disproportionate equity to risk ratio of startup in favor of investor (above 10 % per round), low valuations. Exception are term sheets from Credo, Reflex and Rockaway, which follow Silicon Valley best practices.” – Tytus Cytowski

That sentiment was strongly echoed by Tudor Stanciu, a startup lawyer and advisor from Romania and former organizer of the HowToWeb conference, who wrote:

“I think the biggest problem in term sheets is a general one, especially when dealing with corporate VCs / investment arms: the density of language being used. You see 20+ pages of term sheets/SHAs out of which most refer to standard limitation of liability/disclosures that arise from other types of transactions that the VC’s lawyers have done.

“I think the biggest problem in term sheets is a general one, especially when dealing with corporate VCs / investment arms: the density of language being used. You see 20+ pages of term sheets/SHAs out of which most refer to standard limitation of liability/disclosures that arise from other types of transactions that the VC’s lawyers have done.

At least for early stage, pre-revenue startups, founders do not have the ability to reach out to lawyers and pay out fees to get a language-dense SHA cross-checked and simplified by a founder-friendly lawyer, and that can make a founder end up suffering from “contract fatigue” and missing out on important details oft he transaction while wasting time going through lawyer slang and verbose the effect of which is not that significant, in the end.” – Tudor Stanciu, Startup Lawyer

You Need a Lawyer

There’s an old Russian proverb that the writer Suzanne Massie famously quoted to Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, near the end of the Cold War: “Doveryai, no proveryai” or “Trust, but Verify.”

Trust is a tricky thing when it comes to money. There are absolutely people who can be trusted, but how do you recognize them before the fact? It might be that a person left along in a dark room with a pile of cash might be the type who never even thinks of touching it. The problem is you just don’t know until it actually happens.

Certainly we as investors at StartupYard know that we will not, as a matter of practice and principle, deceive or mislead the startups we invest in. We can tell you this until we’re blue in the face, but we have no way of proving it to you except by following through on what we say. When there is a potential for abuse, there is always a risk of abuse. Recognizing that is an important step in maturing as a company founder.

As we have long noted to our own startups and community, when it comes to early stage and Angel investments, the best protection is your network and the good reputation of the investor. However, taking money from an investor without the advice of qualified legal council is a strategic error, even if it may not lead to catastrophe in every case.

Dealing with a bad actor can just be a case of bad luck. We can’t control how lucky we are, but we can control how prepared we are. So there is no excuse not to be prepared.