5 Questions To Ask Before Sending Any Marketing Email

Recently, one of our startups got a big boost of incoming users. I asked the founder, “what did you do to take advantage of the situation?” “We increased promotion in our channels,” came the reply.

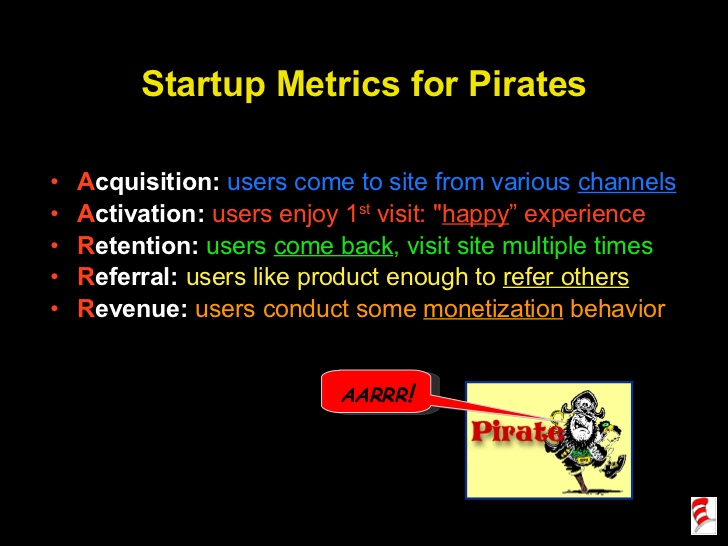

Alright. Well, as we discussed recently, there is a big difference between user acquisition, and user retention. If you suddenly find yourself with a big group of new users on your hands, you have to be focused on retaining them. Andrew Chen pegs the most vital period for activating and retaining users at just 7 days from app install, for mobile apps.

Chen is right when he says that customer lifecycle emails are not the end-all for customer retention or activation. But they can play an important supporting role, particularly if your product has anything like a learning curve involved- that is, if it takes users some time to understand how they can really use it.

Customer retention can be aided even within the first visit, if the onboarding process establishes behaviors and patterns that can be activated again later on. You can show users what life will be like with your product, and get them to “buy in,” by doing a few things right away.

But once you have established a relationship with a user through the product, you will probably want to make use of some smartly timed email marketing to further activate and convert that new user.

After talking with the founder, and sharing some typical email activation and conversion strategies that I have picked up over the years (which I think I will write about more in another post), I thought it might be a good opportunity to pose some important questions that startups should ask themselves before sending any marketing email.

No matter what kind of email you’re sending, these questions can force you to examine the purpose, the content, the goal, and the timing of any marketing email. They are as follows:

1. What Is the Goal?

Before hitting send, ask yourself what you hope to get out of this email. Do it not just in the sense of what your ideal reaction to the email is, like “I want the user to know about a specific feature we have,” but in terms of what the campaign as a whole is meant to do.

Make sure that the email has a goal that is trackable. “Informing our users about a new feature,” is not an easily trackable goal. But it is trackable if, for example, you give those users a way to show they know about the new features, or if you track user behavior before and after the email is sent and read.

This should lead to a few more questions: do I have a success benchmark for this email? Open rate? CTR? Conversions? Hits on a landing page? Engagement with the product? Do I have an easy way for the users to react to this email? Is there a clear CTA (more on that later)?

Try as much as possible to tie the email to some real data points, and to have some expectations for what it will accomplish. If you meet those goals, you can use the experience to replicate the good results. If you don’t, you can look for specific problems, or ask someone else for their input on where it all went wrong.

2. What is your Claim?

Every marketing email -in fact every email- has a basic “claim,” and often more than one. A claim is a statement of fact, or values, which you hope will be received by the person who receives the email. A claim doesn’t have to be said in words, but it has to be felt. It has to come out of reading the email, that this is the reason you are communicating with the user.

Try and spot the claims in this fictional marketing email:

Dear Lloyd,

It’s that time of year again! The leaves are turning, and the snows are inbound! And here at XYZ Inc, we’ve been working on an exciting new way to keep you warm during the coldest months.

Check it out here. Get a special discount of 25% if you purchase before Nov. 30th!

Bye!

XYZ Inc Team

Wow, well I’m definitely intrigued here. So what’s the claim? I can spot a few candidates:

1. You need this product for the winter.

2. We are a cool innovative company.

3. Our products are affordable.

All that was accomplished without directly saying any of those things. But these are very clearly communicated claims.

The claim can be many things. It can be something really simple, like “we care about you.” Or it can be “this new feature will make your experience better,” or “we understand you and your problems.” It can be very direct: “you have 6 days left before your plan expires.” It doesn’t ask users to do anything- that’s for later. Instead, it is simply the broader message of the email.

Try, as an exercise with yourself, to put your claim into clear and specific words, in your own thinking, before you send the email. Ask someone else to review the claim, and tell you what they think it is.

When we are writing community emails to mentors, teams and our community, StartupYard Director Cedric Maloux and I often start with that question: “What are we claiming here?” Then we make a bullet point list of claims we could be making, and we choose the one that is most clear and true to us. Then we make sure that our communication centers around that claim in some way.

So, what is your claim? Force yourself to answer that question clearly.

3. Where is the CTA?

The CTA, or Call To Action, is the thing you will ask your user to do, once they have seen your claim. There is a clear CTA in virtually every email I write- even personal emails. Marketing tricks are, after all, just systems for thinking about normal means of communication.

A CTA is usually directly tied to the goal of the email. What do you want the user to do now? Do you give them a foolproof way of doing it?

I don’t want to speak in absolutes, but it’s difficult to imagine an effective marketing email that doesn’t contain some kind of CTA. A CTA doesn’t strictly have to be a button or a link either. You can have a CTA that doesn’t even lead to your product or site (although the results of such a CTA are harder to track).

A common mistake is for a CTA to be too vague, or to be too complicated. “Please share this on Facebook.” Ok, but where’s the share button? Where’s a link to let me do that?

And another common mistake is to not inform the user of what will happen when the CTA is followed. This is a common reason why people don’t follow CTAs- because they don’t really understand what is being asked of them. Emails come in, and because the author was concentrated on getting the CTA out there, it appears at the top, possibly with several exclamation points:

“Dear User,Click here right now it’s amazing!!!“

Not only is this a pretty good way of getting yourself caught in a spam filter, it also just doesn’t really work. People want to know what they’re really being asked to do before they decide to do it.

You need to set up a CTA with some context, and possibly follow it with some reassurance:

“Dear User,You may be interested to know that we just added a really cool feature we think you’ll like!

Click here to check it out. It’s a way of sciencing your tech using tech science. Cool right? “

Very cool. I’ll check that out, because I know what I’m being asked to look at.

4. What Time Are you Sending this?

This is as much about understanding your own users, as following any specific rules. Will your users get your email at work or at home? How old are they? How late do they stay up? How early do they rise? What time of day are they likely to follow the CTA you send?

Anyone who’s ever received pornography and viagra spam emails knows that they come at night, because that’s when spammers think you’re just loose enough to give them a look. Well, they do that because it probably works.

So take a look at your user’s behaviors, engagement times with your product, and the data you’ve gathered in the past in order to time your emails to maximum effect. Don’t be afraid to experiment! There’s no rule about this. It’s whatever works.

5. Who are you sending this to?

Just as important as what, and when, is who. A really common problem with startups that are growing their marketing efforts via email is that they don’t pay enough attention to grouping and categorizing their users, and sending emails that are likely to have the highest impact for those user groups.

For example, do you ever wonder why so many online services ask for your birthday, despite the fact that there is no conceivable reason why they should need to know it?

Recently i was suggesting to one of our startups that they try a “Birthday Campaign,” which is an old favorite of email marketers, and it goes like this: On the user’s birthday, you send the user a limited time discount offer to upgrade/extend/buy your product, but only within the next 24-72 hours (the details depend on what your goal is, and how long it should take a person to make a buying decision).

It turned out the founder I was talking to was not collecting birthdays in his onboarding process. Too bad! He should start doing that, and see if he can do something with it.

But that’s not the only way to go about it. Companies collect birthday info because they know that people spend more on or around their birthdays and, crucially, they ask people for things they want. Parents give kids money on their birthdays, as do grandparents, and spouses drop hints to each other about what they might like.

And there are lots of personal details that can be taken into account. Should your Christmas campaign really include customers in Israel? Should your back to school discount reach users in their 30s? Should your valentine’s day campaign go to single people? You don’t have to collect an extensive survey on your users in order to learn at least a few things about them, but those valuable bits that you do know can make the difference between a successful campaign, and a flop.